For millennials like me, talkin’ ’bout our generation usually involves complaining. We Generation Zs – or zoomers – can’t seem to catch a break. Even before the pandemic, we were on track to be the first generation worse off than our parents since the Great Depression. It takes us twenty-somethings six times as long to save for a deposit as forty years ago. Having been told by Tony Blair a university education was essential, we leave, saddled with debt, to confront an over-stuffed and unwelcoming graduate market. After spending 2020 locked up against a disease that has a limited impact on young people, we face unemployment and decades of higher taxes to pay off Dishi Rishi’s debt mountain. Unsurprisingly, we’re a tad cross.

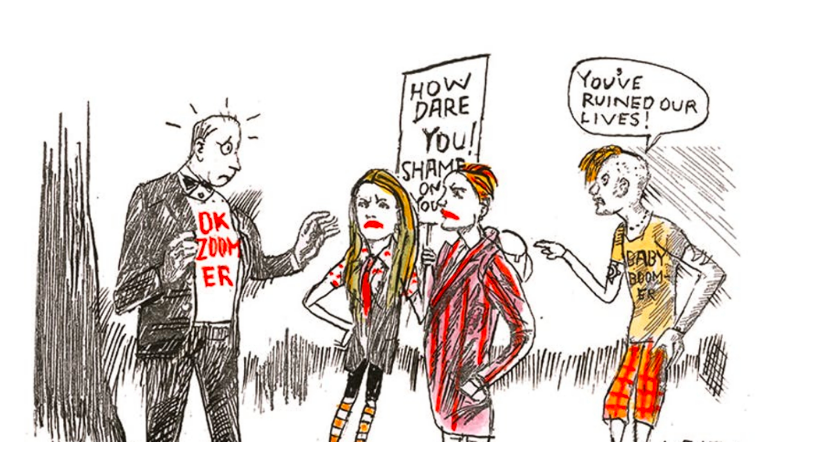

Generation Z has found a scapegoat for their plight: boomers. Used across the Atlantic for decades to describe those lucky babies born post-WW2 into rising affluence, government largesse and expanding expectations, it has become a catch-all term of abuse from those of us under 30. It’s a word slung at an elder generation who many youngsters think has had it easy. They got the Beatles, no tuition fees and index-linked pensions paid out of our taxes. We got Little Mix, a housing crisis and a year lost to coronavirus. Oh, and climate change. As David Bowie – one of the few boomers my generation has begrudgingly forgiven – put it in ‘Changes’: ‘Where’s your shame?/You’ve left us up to our necks in it.’

Generation Z has found a scapegoat for their plight: boomers

But I don’t subscribe to my contemporaries’ boomer-bashing. Complaining about your forebears seems boringly unoriginal. After all, what were Bowie and the Who doing in the 1960s and 1970s? But when it comes to zoomers versus boomers, Corbyn-loving, Extinction-rebelling, bus-pass loathing Generations Zers have not much of a leg to stand on. Our generation has not had things half as tough as we might like to think.

Our employment prospects have undoubtedly suffered this last year, with under 25s hit particularly hard. But, as Matthew Lynn has pointed out, over 50s have not escaped scot free. The percentage of 50-64s unemployed has almost doubled, and the number of age discrimination cases brought to employment tribunals has hit its highest level for three years. In fact, a 2019 ONS study found that the cliché of idle baby-boomers enjoying early retirement at the expense of twenty-something taxpayers is nonsense. Today’s young enjoy far greater state benefits than their boomer predecessors at their age. New Labour’s spending on schools, the NHS and tax credits mean that today’s 20–24-year-olds receive around £4,000 out of the state per year. Those born in the 50s paid in £2,500 more than they received. Young people have never had it so good.

Admittedly, this financial privilege is hardly apparent when you are paying back your tuition fees and shelling out almost twice as much a month on housing as the average boomer had to. Generation Rent is not a myth: those of us aged 16-24 are less than half as likely to own their own homes as thirty years ago, and far more likely to be living with mum and dad into their 30s.

But focusing on housing costs misses all the myriad ways zoomer lives are cheaper and easier. From smart phones and Netflix to Deliveroo and Airbnb, most members of Generation Z lead a life of unimaginable luxury compared to their equivalents a few decades earlier. Children of the 30s and 40s lived through rationing and austerity. Those born in the 50s and 60s faced double-digit inflation, several major recessions, a global financial crisis and the looming threat of nuclear war. Unfulfilled university terms or being sacked from Starbucks is hard, but not that hard.

The problem is that zoomers don’t realise how lucky we are. Going to university was a fantasy for my grandparents; for my parents, it was an unprecedented honour. For me, it was taken as read. In miniature this encapsulates the reason for Generation Z’s resentments. For a generation obsessed with privilege, very few consider how well off they are in a historical context. Complaining about university debt or an expensive mortgage is a welcome alternative to dying in the trenches, rationing or mass unemployment. But my generation take what previous generations thought of as luxuries and treat them as entitlements. As soon as those are challenged, we complain.

Zoomers are as green in their envy as in their politics. It doesn’t help that the post-war generation lead lives that most zoomers assume were much more interesting than theirs’ today. Freud would have a field day with the first generation voluntarily more celibate and sober than their parents. If the zoomer version of sex, drugs and rock and roll involves internet porn, horse tranquillisers and Ed Sheeran, a general feeling of disgruntlement is hardly surprising. Our protesting and posturing is a blatant attempt to compensate for something, a desperate effort to prove we are equal to our cooler forebears. After all, what are Extinction Rebellion and BLM but sad imitations of the folk memory of free-loving hippies and the civil rights movement?

So rather than blaming boomers for our problems and demanding recompense, my generation should reflect on how fortunate we are. 2020 was a matter of life and death for many older than us. Missed nights outs, a few months on Universal Credit, and the terrible choice between cancelling Netflix or paying the rent is hardly comparable. As Bowie didn’t put it, we are hardly under pressure.

Comments