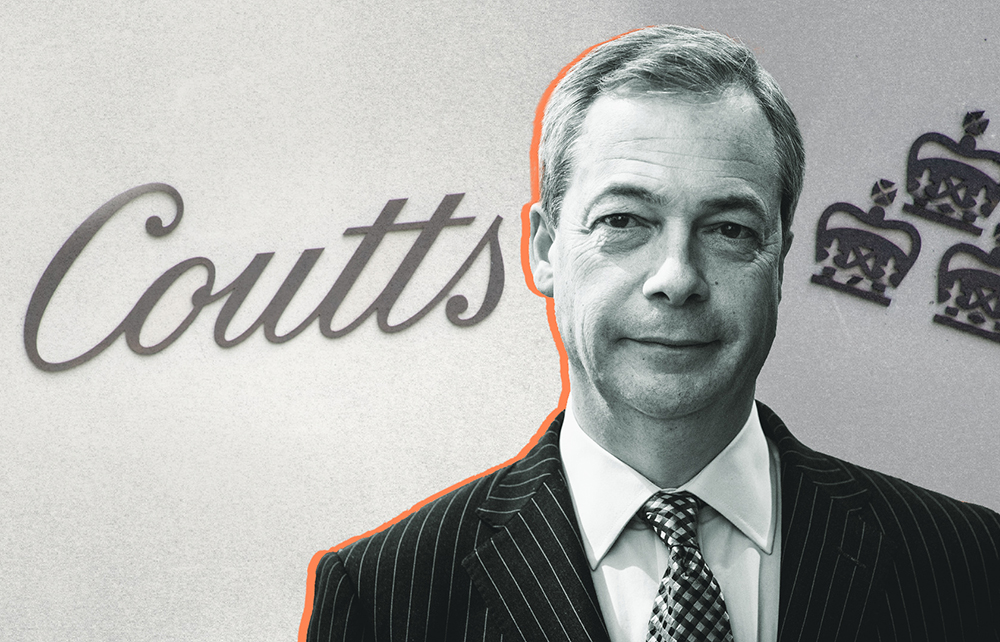

Dame Alison Rose should not have resigned as head of NatWest over the Nigel Farage affair – and ministers who forced this by flinching in the face of a silly media storm should be ashamed of themselves.

In the great Coutts debate this columnist finds himself in a minority. I express no opinion on the wisdom or otherwise of the private bank’s decision to drop Farage as a client, believing this to be a private matter between himself and Coutts.

I’ll pose a number of questions, but first there’s something we must get out of the way. Whether or not Coutts was wise to exclude Farage, a bank like this has, as the law stands, a right to discriminate in its choice of customers.

Customer-facing businesses do often, and should, enjoy a right to reserve admission to premises or membership. No publican could survive long without that implicit right. One of the charming ironies in which our era abounds is that the very people who (as a type) would wax indignant in support of the Garrick Club’s denial of full membership to women, or the Athenaeum’s insistence upon male members wearing a tie at dinner, find themselves on the other side of the argument when a private, members-only institution excludes a would-be customer because his publicly expressed opinion, rather than his gender or neckwear, offends them.

Aren’t there causes that, though lawful, you or I or a respectable bank might consider wicked?

So, point one: a private bank enjoys the legal right to choose its customers. Now for point two. Was the bank’s judgment wise in this case: the exclusion of Farage? I shall not attempt to answer that here. I have an opinion. You may have an opinion. The bank took a view. We can all argue about it.

Or can we? That is point three, and the question I want to discuss in this column. I’m adding to the general noise about the Farage affair only because I haven’t read or heard any attempt to answer it, and it matters. The question is: does a category exist, whether or not Farage falls into it, of clients whom it would be reasonable to reject on the grounds of the public stands they have taken?

I ask, because so much of the Coutts–Farage debate last week appeared to wheel in a somewhat cosmic fashion around the ‘right to free speech’. A typical opening sentence in many of these discussions ran along the lines of ‘Whether or not you agree with Nigel Farage’s views on Brexit [/net zero/Novak Djokovic/etc], and I don’t [/do/will keep my counsel/etc], it surely cannot be right…’ and the commentary then proceeds to maintain the importance of a citizen’s right to express their opinions, and the wrongfulness of any business disadvantaging anyone for their famously declared beliefs.

Woah! The implication here is by no means incontestable. Any beliefs at all? Any level of fame at all? Really? Let’s examine a range of possible beliefs a bank customer might – I say ‘might’ – become famous for publicly supporting. Anti-Semitism (the kind that stays within the law)? Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Insulting the monarch? Anti-vax campaigning? Denying the Holocaust? The persecution of Christians abroad?

I’ve chosen here a few causes that – were a prominent customer of a bank to trumpet them – might particularly enrage some of us on the right-of-centre of British politics. Were I writing for the New Statesman, I might have chosen causes like sending illegal immigrants to Rwanda, re-criminalisation of abortion/homosexuality/blasphemy, ‘anti-trans’ ranters, eugenicists… Each of us has our particular bête noire and no Spectator or NS reader would want their bank to exclude every public apologist for every one of these causes. But quite a few readers would hesitate to join a bank with a famous customer whose name was prominently associated with one or another of them. Remember, we’re not talking about private thoughts or speech, but prominent and public proselytising – and I stress ‘prominent and public’. If someone makes themselves famous for – trades upon – an odious, hateful or even treacherous opinion or association, would it always be wrong for a bank at least to consider what Coutts called ‘reputational’ issues? I think not.

The key phrase, I suppose, is ‘beyond the pale’ – and our leading article last week identified this as the line we should ask whether Farage has crossed, suggesting he had not crossed it. Fair enough. But what if someone did? Our leader points out that if disliking the EU is beyond the pale, so are millions of our countrymen. Fair point. But how about one of those dodgy imams the press call ‘preachers of hate’? They might attract large numbers of followers yet still be – in your or my eyes – beyond the pale. Aren’t there causes that, though lawful, you or I or a respectable bank might consider wicked? Without censoring anyone, may we not decline to associate ourselves with them? The problem with discussing this as though it were just a question of freedom of expression is that the argument is too strong.

A final point: there’s no way we can in principle distinguish between removing an existing client for given reasons, and for similar reasons declining to accept someone who applies for an account. But banks turn down applications all the time, often to the fury of the applicant. Are we suggesting that applications either to keep or to acquire a bank account should be in some way publicly justiciable if the would-be client does not like the decision? Our leading article’s call last week for some kind of official inquiry in Farage’s case would point, in logic, that way.

Sooner or later someone will suggest that government should ‘step in’ and establish an appeals process. Then, sooner or later, someone will suggest that now the principle is established that a private bank’s procedure for selecting its clients should be regulated, the same principle should apply to other businesses and membership organisations. First they came for Coutts, and I said nothing… finally they’ll come for the Garrick.