The British constitution is best understood as a dinner party. Imagine the key institutions of national life personified and sat around a table debating the issues of the day. True, as you and I picture this scene it is now a little late in the evening, the surroundings are worn and some hitherto unheard voices are beginning to loudly bark above the polite murmur of the older interlocutors. But the conversation carries on.

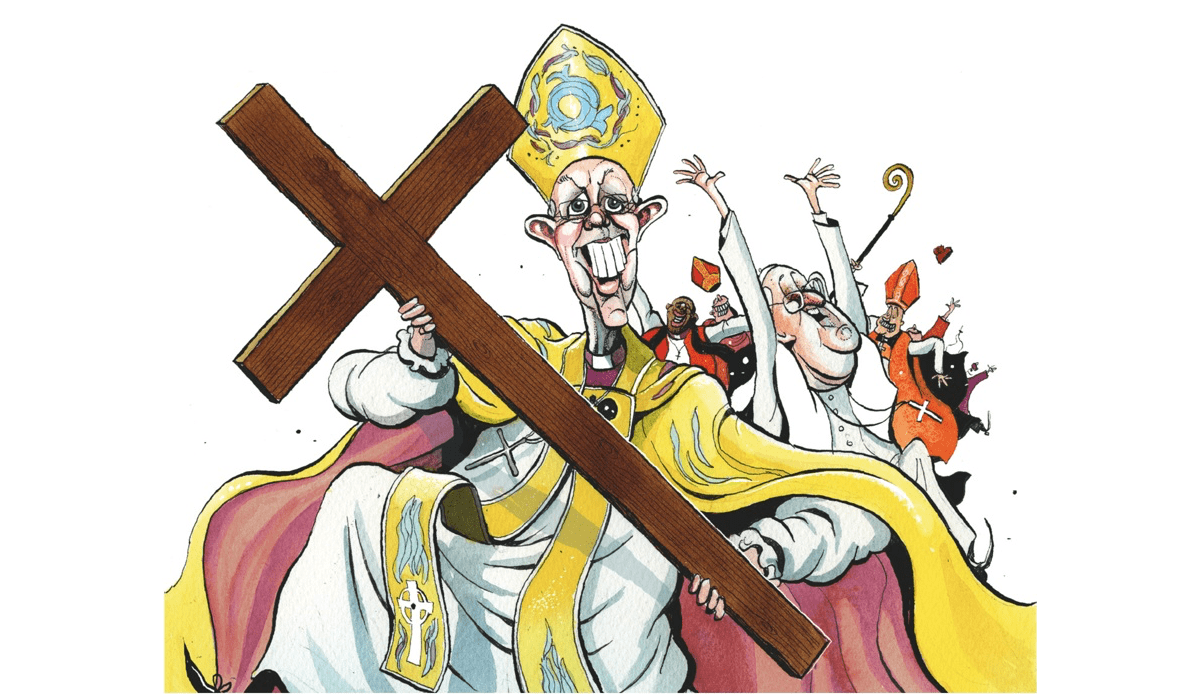

One of the longest-standing participants in this national conversation is the Church of England; indeed, perhaps only the Crown has been part of it for longer. The traditions of Toryism and liberalism are comparative newcomers, Labour even more so. The BBC and the NHS have barely graduated from the children’s table. Yes, her bishops occasionally come across as a hectoring maiden aunt, imposing unwelcome interjections on the younger guests, invariably blundering in with particular awkwardness when sex or money is mentioned – but the Church’s place at the table has long been assured.

The Church’s bishops have clashed with government policy innumerable times before, from subjects from Oxbridge and Ireland to Apartheid and Iraq. Now they have done it again, mounting an intervention against the government’s Rwanda policy, saying that the ‘immoral’ policy ‘shames’ Britain.

Some Conservative MPs are beginning to sound worryingly like the adolescent debating society-types who run the National Secular Society

This intervention came in the form of a public letter signed by all the bishops who sit in the House of Lords. It wasn’t a brick chucked at a biking Boris by an irate Justin Welby, nor was it soiled underwear hurled in a dirty protest by the Archbishop of York at Priti Patel. Instead, it was a polite, official, open letter, written by members of the legislature and leaders of one of the nation’s most important institutions, voicing concern about a particular – and not uncontroversial – policy. Quite why there has been such recent surprise – more apoplectic rage in some conservative quarters – about this very mild display of gobbiness is, therefore, perplexing.

That is not to say that all the Church’s public pronouncements are without sin. An obvious problem is that such interventions come from an ecclesial establishment – for all its recent commitment to diversity – that is politically, intellectually and culturally monochrome.

There seems to be a stubborn unwillingness to learn that public interventions land more convincingly if the Church’s shepherds were less keen on steamrollering dissent in the dioceses. Or if they occasionally threw a political bone to the (predominately conservative) parishioners in the pews. However, there are glimmers of hope. The Bishop of Chelmsford’s recently criticised managerialism and jargon in public life, hitherto sacred cows for the central CofE. It may not have made headlines, but it suggested that a tide might be turning.

It is worth remembering, too, that Christianity compels its adherents to weigh up decisions in the light of the teachings of Jesus. That some of its key public proponents have done so, found a particular policy wanting, and then have said so should only be a shock to someone who has slipped into a coma at the height of the Cromwellian Commonwealth and only just woken up.

In response, some Conservative MPs are beginning to sound worryingly like the adolescent debating society-types who run the National Secular Society (presumably from the library computers during school break time). On Twitter, vague threats about the Church’s future are combined with wild comparisons between the Church of England’s rather drab public advocates and the Ayatollah of the Islamic Republic of Iran. All because the bishops dared to use the voice that the constitution – and indeed the basic rules of a free society – gives them.

The Tory party of the past spilt much blood and treasure ensuring that the bishops had that voice. It was never on the understanding that they would only say things the party wished to hear, but instead because of a matter of principle. The Church of England ought to be part of our national conversation.

The question that arises from the current furore is not one about the Church of England’s role and purpose within the life of the nation, but rather one about the role of the Conservative and Unionist party. If that august body no longer believes in the concept of a national conversation where the ancient institutions of Church – and, indeed, Crown – get a voice; then what, pray, is its purpose?

Comments