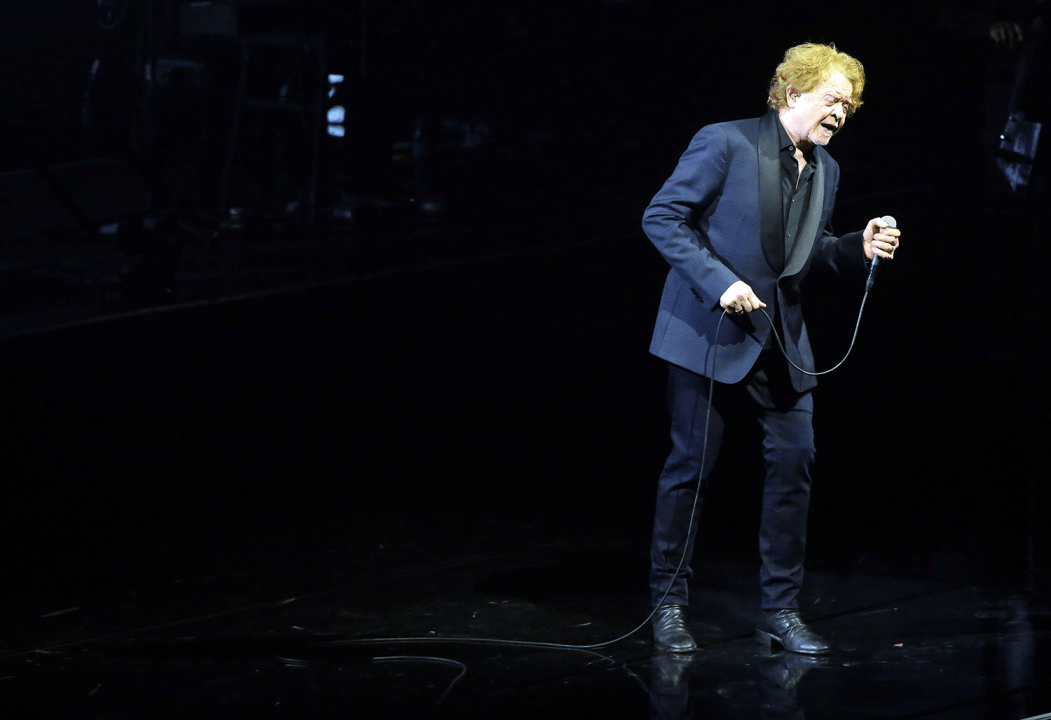

Before Simply Red came on stage at the Greenwich peninsula’s enormodome, the screens showed a clip of a very young Mick Hucknall being interviewed. What he wanted, he said, was to be a great singer. Usually, that’s the cue for a gag about fate having other plans. Not this time. He’s 65 now, and he truly is a great singer as he showed for the best part of two hours.

He knows it, too. A couple of songs in, he benignly told his audience at the first of two nights at the O2 that he liked it when they sang along with the choruses, but maybe leave the verses to him. The person next to you, he explained, had come to hear him sing, not you. But not just hear – Hucknall is worth watching as well.

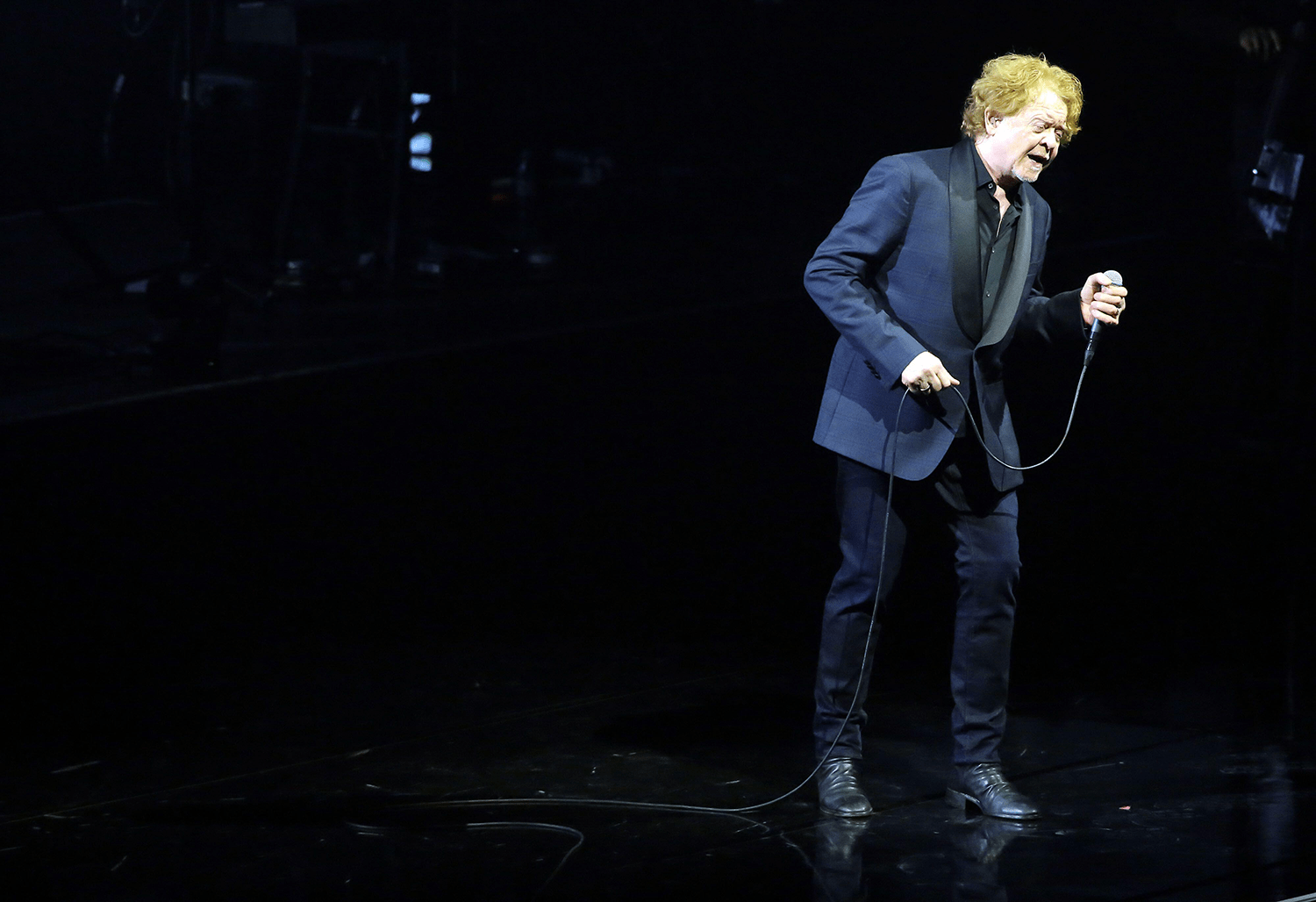

Seeing him was like witnessing one of the great standards singers of the 1950s. For Hucknall does not merely step up to the mic and bellow it out. His microphone – a Telefunken 250; the same type he has always used – is an instrument. One that he rarely holds to his mouth, moving it instead carefully and deliberately, different distances, different heights. Just like Sinatra did.

The result is that one could hear every single word, and every single variance of tone and timbre. Never did anything topple over into distortion; I doubt the sound engineer ever had to slide the faders: Hucknall took care of all the volume variations himself. He still has the vocals of his youth, but now there is the hint of gravel, too, and it’s marvellous to hear.

For many years, Hucknall was a punchline: the king of Mondeo soul. He was mocked for living the love life of a Jagger while being ginger (ignoring the fact that curly, ginger, Mancunian men called Michael are known worldwide as the greatest lovers. I speak from experience.) He lived in the tabloids, and the music press regarded him very sniffily.

Perhaps there was a certain resentment from critics. Hucknall should have been cool: he was one of the 42 people who was actually present at the legendary Sex Pistols show at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in 1976 – along with future members of Buzzcocks and Joy Division, and the founders of Factory Records – which kickstarted independent music in Manchester. He loved all the right music; he put his money into the reggae reissue label Blood and Fire. But it was not to be – in Michael Winterbottom’s film 24 Hour Party People, God (played by Steve Coogan) is seen telling Tony Wilson of Factory (played by Steve Coogan): ‘You were right about Mick Hucknall, his music’s rubbish – and he’s a ginger.’

He moves his microphone carefully and deliberately, different distances, different heights. Just like Sinatra did

But seeing a band as good as this – and guitarist Kenji Suzuki, looking like a Japanese Walter Becker, really was brilliant in a restrained way, reminiscent of Steve Cropper of the M.G.s – playing songs as good as ‘The Right Thing’, ‘Fairground’, ‘A New Flame’, made you realise why so many millions bought their records. I used to think Hucknall was rubbish too, but the older both he and I get the more I feel a little bit in love with him.

The O2 gets a bad rap, but it’s still my favourite of the enormodomes. It seems to have conquered the issue of poor sound that bedevils big spaces. Sure, it’s soulless, but it’s also entirely fit for purpose. The 100 Club, on the other hand, is entirely unfit for purpose yet remains the most vivid and atmospheric live music venue in London and I will go to see more or less anything there. The row of pillars right in front of the stage does not deter me; the reliably poor sound does not deter me; the appalling shape of the room does not deter me.

I used to think Hucknall was rubbish too, but the older both he and I get the more I feel a little bit in love with him

Sometimes, though, the room defeats the artist. Katy J. Pearson is brilliant: a wonderful singer and spiky, melodic songwriter, playing something equivalent to a meeting between early Fairport Convention and peak Fleetwood Mac. But at the 100 Club, mics kept feeding back, her violinist was inaudible, songs had to be stopped and restarted. Not her fault, and no one minded, because it was a benefit for the charity War Child, but it reminded me how much is in the lap of the gods when a band plugs in a bunch of instruments in front of a bunch of people. It’s not as easy as Mick Hucknall made it look.

Comments