Horatio Nelson passed his examination for lieutenant on 9 April 1777 (possibly with a little help from his uncle, who was one third of the examining panel). He was then just 18 and a half years old, and yet he already had six years of naval experience. The man who was to become England’s greatest fighting sailor had served in the West Indies and the Arctic, and had spent two years on the India station, at a time when sea voyages to India could take as much as six months each way. He had seen combat, albeit a brief and insignificant skirmish, and had recently recovered from a serious bout of malaria. All this before he reached the point at which most modern youngsters leave school. His was not an especially unusual trajectory for the time. It was common for boys to go to sea around the start of their teens and to have obtained an officer’s commission by their early twenties.

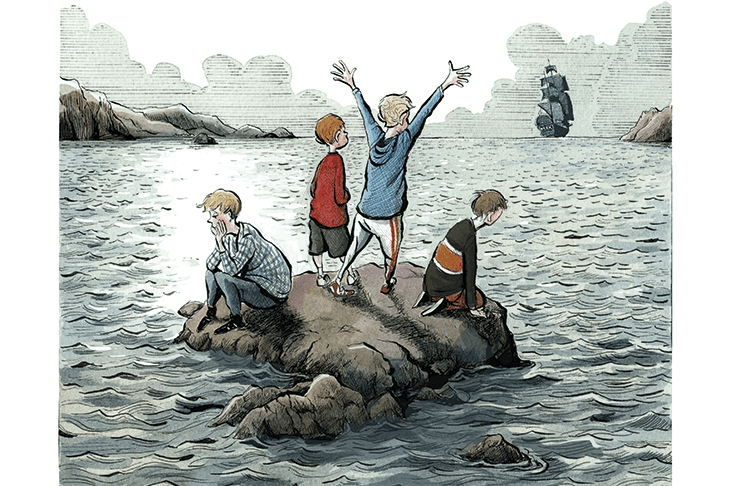

There were of course many cruelties and horrors attendant on teenage boys going to sea in the 18th century navy. But equally, that old system did provide an outlet for boys’ natural desire for adventure, achievement, responsibility and excitement, and to induct them into the world of men in a meaningful way. It is also an excellent illustration of the extent to which our expectations of what boys can and cannot do are very strongly shaped by the arrangement of society, rather than by any inherent physical or mental limitations. There is a fantastic scene in the film Master and Commander in which the very young midshipman Lord Blakeney – who has already endured the amputation of an arm sans anaesthetic with barely a whimper – dines with Captain Aubrey and the other officers, all older men, and the viewer can see that through his shared experiences and adversities with them, and his growing mastery of himself and his skills, he is being inducted into the world of adult male comradeship.

The values, aspirations and behaviour of teenage boys have been the subject of much debate and discussion in the last few weeks, following the release of the Netflix mini-series Adolescence. The whole machinery of official concern has sprung into action. Keir Starmer has been perfecting his worried face behind a podium in Downing Street. Newspaper columnists have demanded change. Questions have been raised in the House, by MPs who insist that the government must act to address the made-up events performed by actors that appeared on the screen in the corner of their living-room. Should we ban phones? Should we ban Andrew Tate? Should we have special lessons for boys where they are taught how not to be misogynists? Something must be done.

No doubt there are many problems in contemporary youth culture. I have my own concerns about smartphones and social media. However, I would like to put those to one side for a moment and say a word in favour of teenage boys, who have been the target of so much direct and indirect opprobrium in recent weeks. They have been slandered as ticking timebombs of misogyny and sexual entitlement, full of rage and violence, unable to cope with the changing modern world.

Beyond these panicky stereotypes, there is another, very different story about teenage boys. We should cherish their love of scabrous and iconoclastic humour, because we will always need to puncture the hectoring piety of complacent establishments. And what about their admirable impatience with humbug, and their restless energy? These are the kind of characteristics typical of young men that other eras seem to have worked out how to channel and honour, in ways that we have often forgotten. Our society is dominated by labyrinthine speech codes, by policies and procedures, by a political-legal culture that prioritises safety, comfort and consensus over action, agency and robust but impersonal disagreement, which is to say that it penalises and suppresses a classical male mode of existence and discourse.

Instinctively, teenage boys value strength, humour, courage and prowess. They want, consciously or not, to prove themselves to one another and to the adult world, especially the adult male world. Any boy who has played on a sports team with men will understand this instinctively. When I was 15, I went to the Yorkshire Dales on a winter walking trip with my older brothers, who were then 27 and 23, and one of their friends. We climbed several peaks in heavy snow, with a freezing wind slicing through us. The zips on my rucksack froze solid. But the thing I remember most of all is wanting to demonstrate my endurance, like most boys of that age. And this is a good impulse. It is good that young men prize stamina and skill. It is good that they want to push boundaries and impose themselves on the world and impress girls. Their disdain for nagging, their reluctance to be scolded and boxed in, is commendable, even if it sometimes causes problems for the adults around them.

If you read biographies of men who have distinguished themselves in some field of human endeavour, especially ones requiring physical bravery and mastery, it is common to come across incidents of adolescent rule-breaking. It seems like war heroes and pioneers of mountaineering were forever sneaking out of their boarding school dormitories to test their nerve by ‘roofing’ or getting into fights. George Mallory, who very nearly reached the summit of Everest in 1924, honed his climbing skills by sneaking out of Winchester College to clamber about on the ruins of the bishop’s palace. It is near-compulsory nowadays to tut at the saying that ‘boys will be boys’, on the grounds that it allegedly excuses bad behaviour. But the basic truth of this expression – that we should give young men a certain amount of leeway as they develop their ambition, their drive and their abilities – is highly important. The world needs men, and if we want good men who will do great things, we need to salute the fiery, irreverent, independent spirit of the teenage boy.

Comments