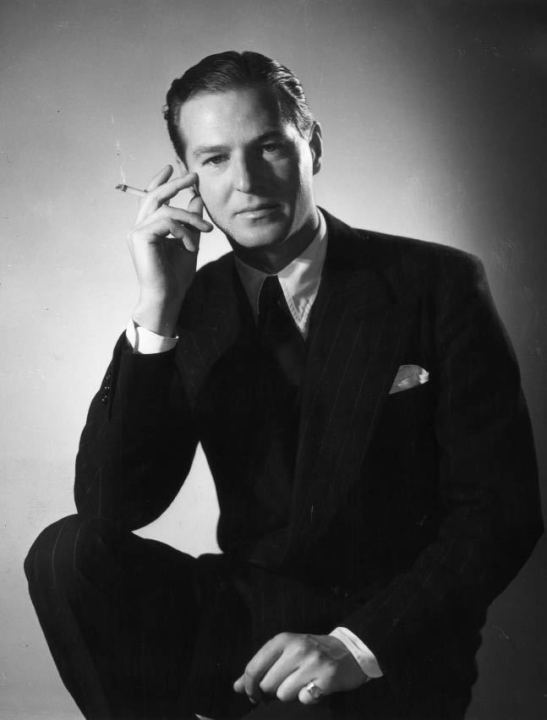

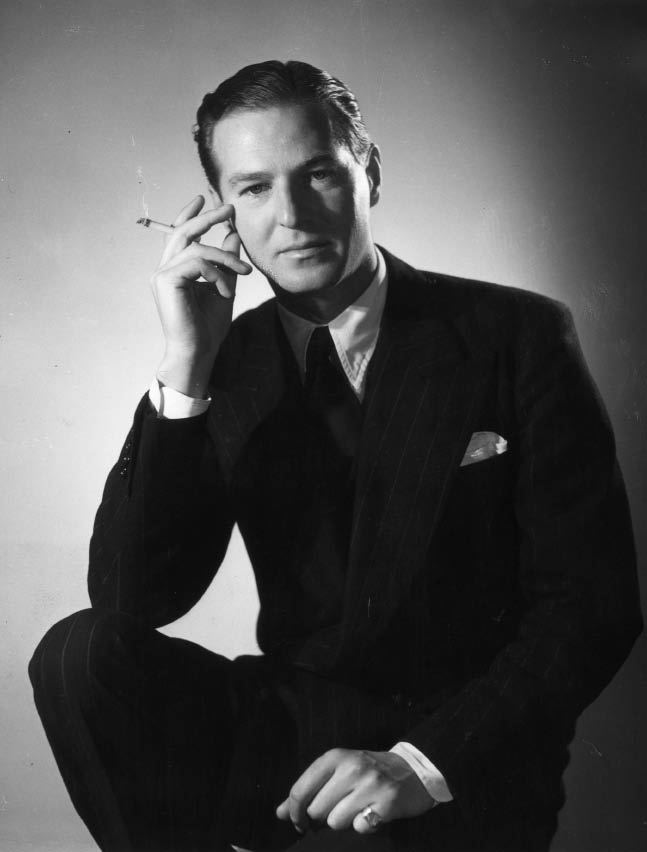

Philip Ziegler puts the case for Terence Rattigan, whose centenary is celebrated with numerous revivals of his work

After decades in the doldrums, Terence Rattigan seems once more to be returning to popular and critical favour. Last year After the Dance was one of the National Theatre’s more emphatic successes, and the centenary of Rattigan’s birth is being celebrated by productions of his plays at the Old Vic, the Jermyn Street Theatre and in Northampton, West Yorkshire and Chichester. There is to be a Rattigan season at the British Film Institute, and a new screen adaptation of The Deep Blue Sea. Rattigan, it seems, is back.

Of course, he never really went away. His plays have never ceased to be standard material for repertory or amateur productions and though his films were rarely shown they were never totally forgotten. But nor, in terms at least of critical esteem, had he ever been entirely there. After various sighting shots his career began triumphantly in 1936 with French Without Tears, an uncomplicated and high-spirited farce based on his own experiences at a crammer in France. James Agate loathed it — ‘It is not witty. It has no plot. It is almost without characterisation’ — but he had to admit that it was a spectacular success. Most of the other critics liked it; the public loved it. Rattigan was hailed as the new Noël Coward. Unfortunately for him, it was assumed that his talent to amuse would be the hallmark of all his future work.

Though he scored several other successes during the second world war, it was not till 1946, with The Winslow Boy, that it occurred to the critics that he might be more than an accomplished farceur. Within the next few years came The Browning Version, The Deep Blue Sea, Separate Tables. These were clearly more than the products of a skilful craftsman; they presented convincing and compassionate studies of ordinary human beings who, for one reason or another, were subjected to extraordinary pressures which they found hard to bear. Of Separate Tables, or at least the second of the two plays that made up the evening’s programme, Harold Hobson wrote that it was Rattigan’s masterpiece, ‘in which he shows in a superlative degree his pathos, his humour, and his extraordinary mastery over the English language’.

Yet even when he was at the peak of his career, the conviction remained that he was no more than an accomplished artisan: a Pinero, a Maugham, a Galsworthy, worthy enough but without a trace of genius. It was largely by his own doing that he earned this reputation. He made a great deal of money, enjoyed spending it, and carefully avoided anything likely to shock or distress his huge but predominantly middle-class following.

To justify his approach to drama, Rattigan invented Aunt Edna: a conventional middle-aged maiden lady, neither a fool nor a bigot but relentlessly opposed to the daring, the obscure, the avant-garde. Aunt Edna was not to be blindly followed, said Rattigan, but nor was she to be ignored. He never ignored her. Though he himself might have expressed them more tentatively, the views of Aunt Edna were the views of Rattigan. When she went to see Waiting for Godot Aunt Edna enjoyed the evening but not the play. There was no play, she protested. Beckett, she supposed, was a highbrow, ‘but even a middlebrow like myself could have told him that a really good play had to be on two levels, an upper one, which I suppose you’d call symbolical, and a lower one, which is based on story and character’.

The ready acceptance of Beckett by the London audiences, or at least by the more adventurous of them, showed that Aunt Edna, like her creator, was fatally out of touch with the times. Two years later John Osborne’s Look Back In Anger launched a ferocious attack on all the values which Rattigan held most at heart. Rattigan went to the first night with Binkie Beaumont, that stalwart of the traditional West End theatre. Both men hated it, Beaumont left at the interval, Rattigan was persuaded to stay but was only reinforced in his dislike. Asked by a Daily Express reporter what he thought of the play, Rattigan rashly replied that what Osborne was saying was, ‘Look, Ma. I’m not Terence Rattigan!’

By thus personalising the issue Rattigan presented himself to the world as a beleagured rearguard, resentful of the new wind that was blowing through the British theatre. He did himself a grave injustice. Rattigan was, in fact, far less at variance with the world of Osborne, even the world of Beckett and Pinter, than he cared to admit. But his picture of himself as the champion of those values which the new wave had ruthlessly discarded became the accepted wisdom of the age. When it came to the point, the public concluded that those values were fusty and irrelevant and that both they and Rattigan should be discarded.

It is easy to exaggerate the completeness of his eclipse. Rattigan continued to earn a large amount of money. Ross, his play about Lawrence of Arabia, was on the whole well received. But Kenneth Tynan, the most persistent and acute of his hostile critics, disliked it. ‘My main objection,’ he wrote, ‘is not that its view of history is petty and blinkered…What clinches my distaste is its verbal aridity, its flatness of phrase.’

Tynan did more than any other critic to demolish Rattigan’s reputation. Rattigan, he claimed, was ‘the Formosa of the contemporary theatre, occupied by the old guard but geographically inclined towards the progressive’. Formosa, an off-shore island, by-passed by history, hopelessly divorced from the march of progress in Communist China, must have seemed an admirable metaphor for an outdated dramatist: the fact that, as Taiwan, it survives and flourishes economically today suggests that dramatic critics, like political commentators, are not always right in their predictions.

Tynan set the fashion, however. Rattigan might anyway have gone into partial eclipse but the total darkness that now encompassed him was largely the work of that brilliant but malign polemicist. He particularly disliked Variations on a Theme, a slight and decidedly lacklustre updating of La Dame aux Camélias, and his view was shared by a young photographer’s assistant in Salford who saw the play during its pre-London provincial tour and, in furious reaction, dashed off her own first play, A Taste of Honey. She sent it to Joan Littlewood, who put it on in her Theatre Workshop. It opened in London only a few weeks after Rattigan’s new play, was an immediate and emphatic success, transferred to the West End and ran triumphantly long after Variations on a Theme had vanished into obscurity. Its author followed his creation. Rattigan’s last few plays were not conspicuously worse than the successes of his prime but he had ceased to figure in the popular mind. He was dismissed as a pathetic has-been and remained so until his death.

Has he at last found his proper level? Ibsen, Strindberg, Brecht, Beckett, Pinter: like them or not, these are titanic figures who changed the course of the mainstream of European drama. Rattigan floated with the current and left hardly a ripple on the surface. Yet not many playwrights enjoy so striking a revival more than 30 years after their death. Rattigan deserves it: not just because his craftsmanship was unfailing but because his humanity shone through, he created characters whose sufferings were poignant, whose tiny triumphs were hard-earned, and with whom the audience could identify and fully sympathise. The plays are still relevant in 2011: there seems no reason to doubt that they will be equally so 50 or 100 years from now.

Comments