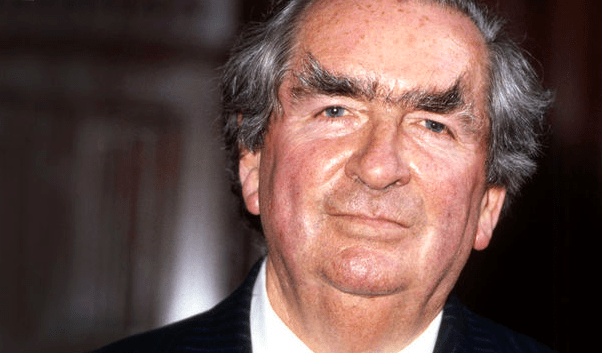

Denis Healey, who has died at the age of 98, never led the Labour Party – but it still owes as much to him as to any post-war politician. And not just because of his time at the Treasury. The statements released by Labour figures tonight scarcely do him justice. Of course, he was a “towering figure” – but he was much more than that. He saved the Labour Party from itself, and saved Britain from the worst of the Labour Party. And when the crunch came, he rose to the challenge: bringing expenditure reform more radical than any Tory Chancellor has been able to enact.

As secretary of Labour’s International Committee, Maj. Healey was the expert who fashioned the arguments that kept unilateralism at bay in the 1950s. He was an authoritative and decisive defence secretary in 1964-70, fighting his party’s anti-nuclear and anti-American instincts. By his own admission, he made a disastrous and start to his long stint at the Treasury. He spoke about a wealth tax (and idea popular with some Tories today) but soon worked out it was unfeasible. He dropped the idea, and then became a full-blooded convert to embraced economic realism – pulling Britain out of its nosedive some three years before Mrs Thatcher took over at the cockpit.

The crisis of 1976 (and the IMF bailout) was the economic turning point for the UK. The 1979 election simply continued the trajectory of monetarism and fiscal sanity. As it turns out, no one did austerity better than Denis Healey – before or since. He found more savings in one year than George Osborne was been able to find in nine years (see graph, below). He was pilloried for it by Labour activists at the party’s conference in Blackpool – an ugly sight which, as Thatcher remarked afterwards, the country was ‘unlikely ever to forget’.

The Conservatives often like to remember the 1970s as a long disaster, rescued only by Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979. In fact the Healey’s 1976 budget was the hinge of history, as The Lady herself recognised. In June 1976, he announced a money supply growth target of 12pc – the first time such a target had ever been set by a British government. Monetarism was a Healey invention. By October 1978, he said that he was determined to control spending growth so that the fiscal policy was “consistent with” his new monetarist stance.

Healey’s 1976 budget introduced monetarism and cut spending more in one year than Osborne would do in nine years

The Lady herself was impressed, later admitting in her memories that Healey…

…announced deep cuts in public spending and borrowing, and targets for the money supply… It was, in fact, a monetarist approach of the sort which Keith Joseph and I believed in and it outflanked from the right those members of my own Shadow Cabinet who were still clinging to the nostrums of Keynesian demand management… [This was] the turning point, for under the new financial discipline the economy began to recover.

She graciously made a point that neither Labour nor the Tories like to admit: Healey’s austerity worked and his budget saved the British economy. Things were already coming right in 1979, and Thatcher simply continued the Callaghan/Healey trajectory.

Healey was probably the only Labour chancellor who could have pulled the country through the crisis of the mid-1970s. He was the favourite to succeed Callaghan as leader, but when Labour chose Michael Foot instead it also chose defeat in the subsequent election. He (narrowly) defeated Tony Benn for the deputy leadership in 1981, a decision that probably saved Labour from complete collapse. He turned down the secretary-generalship of Nato in order to that contest – an inspiring example of putting duty to his party well ahead of personal ambition.

Writing in 1989, he was still trying to persuade Labour not to be so self-indulgent.

“We use to describe the period of Conservative Government from 1951 to 1964 as ‘thirteen wasted years’. The first eleven of those years were wasted by the Labour Party. Our bitter internal wrangling at the time gave us a reputation for division and extremism from which we have not yet recovered.”

Wise advice, needed now more than ever. RIP.

Comments