Britain is not blessed with an abundance of amphibians. There are just seven native varieties. The loss of ponds – whether in gardens, farmland or in areas earmarked for development – has seen a dramatic decline in habitat for one of the seven in particular, the great crested newt (or GCN for short). Its rarity means it is protected by law, making it an offence to kill, injure or capture one, or damage its habitat.

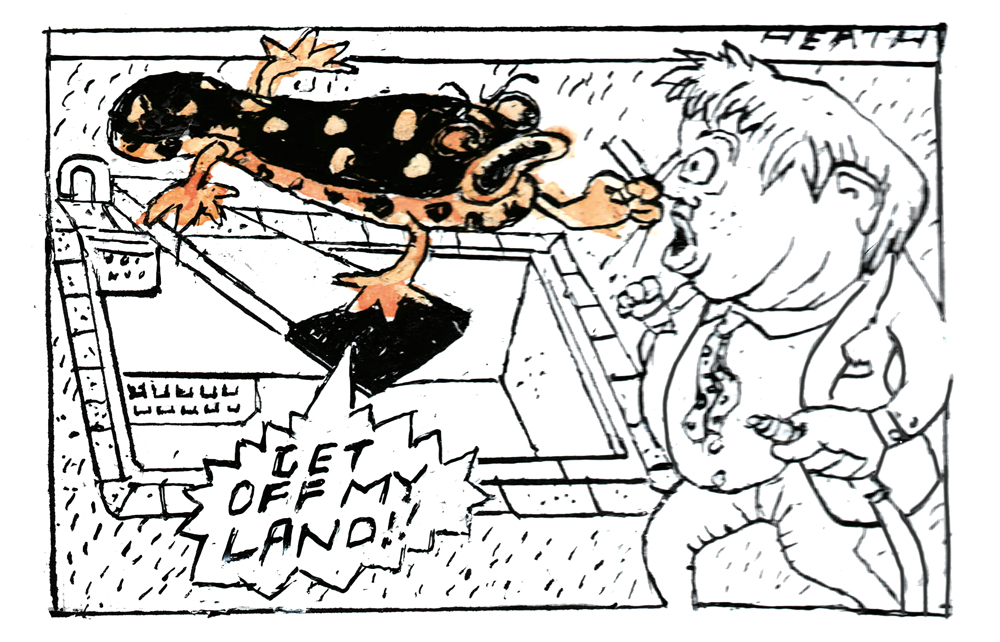

That is why for construction firms, road builders and, most recently, Boris Johnson, no newts is good news. The discovery of GCNs at Johnson’s Oxfordshire pile meant planning permission for a swimming pool was refused. A couple of years earlier, as prime minister, Johnson had decried the ‘newt counters’ responsible for holding back the development of homes across the UK.

The great crested newt has become a poster boy for wildlife conservationists. At up to 17cm long, it is the biggest of our amphibians, which includes three types of newts, two frogs and two toads – some of which went into the witches’ cauldron at the start of Macbeth (‘Eye of newt and toe of frog’). Of the three newts, the great crested variety is the most stunning. It is a shame that so few people get to see one unless they are lucky enough to live in certain parts of the country.

Triturus cristatus, to give it its Latin name, is a rather pedestrian black with white sides when viewed from above but underneath it goes from monochrome to Technicolor with a striking orange belly punctuated with black spots, each pattern unique like an amphibious fingerprint. It is the males that have a long wavy crest along the back and tail which they use during the breeding season to attract females, along with an athletic courtship routine which includes waving their tail around while standing on their front legs.

While it is natural to associate newts with ponds, they spend most of their time on land hunting insects in the hedgerows and long grass during the summer and waiting out the winter safely hidden in muddy areas, even compost heaps. They need ponds, even garden ones, though preferably in open land where there is a network of ponds across a larger area. This is because it helps to grow the spread of the species. Not least because GCNs eat tadpoles, including their own. But they also need hedgerows, grassy areas and banks, so simply protecting a pond is not enough for those building a housing estate, or a swimming pool.

In ancient Greece, newts were associated with the god of fire, and were believed to have the ability to withstand flames. In more recent times, their best-known literary reference is the 1936 satirical sci-fi novel War with the Newts, by Karel Capek, in which a race of enslaved super-newts evolve human knowledge and use it to battle humans for global supremacy. Boris had better be careful who he messes with. Perhaps in a bid to make peace with the creatures, he wrote in his Daily Mail column: ‘I believe that it is our job to protect them and do everything we can to make sure they do not suffer the continual decline in population that we have seen.’

Over the past 40 years it is estimated that the UK has lost around half of its ponds because of changing farmland use, housing developments or simply fewer gardens. Newts will also avoid poor quality water that has the wrong pH level. So when you do see one, it indicates a very good quality local water source.

Comments