If you peer deep into the statute book, you will see that it is still an offence to enter parliament wearing armour. Even more amazing, it has been a crime since 1313.

I mention this because the moment has again come for parliament to clear some of the redundant legislative noise off its books. This is a time-honoured process, and one that is becoming increasingly complex thanks to the sheer volume of modern legislation.

A cursory wander through a suitable library will reveal that the statutes passed during the reigns of our medieval monarchs are neatly grouped together in a handful of surprisingly slim volumes. Back then, good rule was not measured by the legislative yard. But shuttle forward to today, and libraries need several shelves for every year of parliament’s output. To give some perspective, Magna Carta is traditionally divided into a mere 63 clauses, whereas the Blair government legislated on such an industrial scale that its oeuvre in criminal matters alone amounted to over 3,000 new offences, or around one a day for their nine years in office. (That said, we have to thank the Thatcher government for that most weighty modern offence of ‘handling salmon in suspicious circumstances’.)

As the next wave of repeals goes through, few people will miss a vast swathe of impenetrable tax laws from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Likewise the 1997 act allowing for referenda on a Scottish parliament and Welsh assembly are now surplus to requirements. But the 1865 act to help the Assam tea company in British India is an interesting reminder of the brute economics at the heart of empire, while an obscure provision on landlord and tenant law is perhaps the jewel of them all.

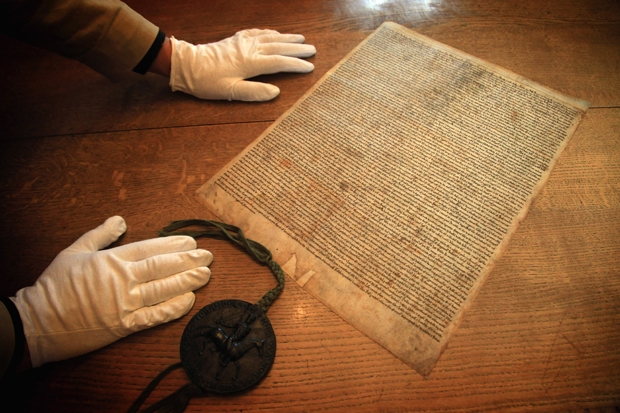

It is part of the Statute of Marlborough, our oldest piece of surviving parliamentary legislation. It dates to 1267, to a parliament held by King Henry III in the Wiltshire town, and is notable for lots of reasons, including the fact it pre-dates Magna Carta, which did not become parliamentary law until 1297.

By far the Statute of Marlborough’s most important provision forbids revenge against debtors without the involvement of the courts. Yet of its original 29 sections, only four lone provisions remain unrepealed. The Law Commission is now proposing to cull two of these four, as they relate to the concept of ‘distress’, a landlord’s remedy which has not survived the new regime brought in by the rather unmemorably titled Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2015.

As we prepare to ditch half the mortal remains of our oldest statute, it is worth looking at what else has been quietly repealed over the years.

The most notable, surely, is Magna Carta itself, which once had a whole host of things to say. Despite a widespread belief that Magna Carta is somehow a sacrosanct pillar of this country’s laws, in fact only three of its provisions have survived waves of zealous repeals: freedom of the English Church from royal interference; respect for the customs and liberties of the City of London and other cities; and no sale of justice or imprisonment of a free man without trial by his peers.

In all honesty, even though this year is the octocentenary of the 1215 Charter of Liberties (Magna Carta’s predecessor), what is left of Magna Carta is not really a great deal of legal use to anyone today. King Henry VIII drove a juggernaut through the requirement that the monarch stay out of the affairs of the Church when he made himself head of it. The freedom and customs of cities are now largely ceremonial. And the right to trial by jury has been hacked away incessantly by the mission creep of magistrates and plummeting legal aid budgets.

It is entirely logical and orderly to repeal obsolete acts and broken cross-references. But in doing so we risk losing some glorious oddities, whose value sometimes lies precisely in the fact they have survived so long, innocuously, beyond any meaningful relevance. Is it therefore truly necessary to repeal so many historic statutes? If the provisions in them have been superseded, or if their realistic legal impact is zero, then what is wrong with leaving them on the books, adding gravitas and continuity to the foundations of parliament and our uniquely historic law?

For instance, the death penalty was temporarily abolished in 1965, then permanently in 1969. But a handful of historic capital offences clung on in dusty corners of the legislative locker, until individually repealed. They included death for arson in the Queen’s docks (abolished 1971), espionage (abolished 1981), piracy with violence (abolished 1998), treason, including violating the princess of Wales, the king’s wife, or the king’s eldest daughter (abolished 1998), and a number of military offences (abolished 1998). The reality is that these sanctions were never used after 1965, and likely never would have been, although HMP Wandsworth did rather dutifully keep a working gallows until 1994. So did these laws really need to go? Some of their provisions were spectacularly ancient and historic. For instance, the statutory death penalty for treason goes back to Edward III’s Treason Act of 1351 (parts of which are still in force).

The survival of the few outdated and meaningless provisions of Magna Carta 1297 and the charming but pointless 1313 ban on wearing armour in parliament prove that we may keep certain statutes for their historic value and inherent cultural interest rather than their modern functional relevance. So as we wave a sad goodbye to half the four remaining clauses of the Statute of Marlborough 1267, let’s hope they leave the remainder, and in two centuries’ time parliament can celebrate its oldest act’s one thousandth anniversary.

Comments