After the verdict of the referendum had been announced, the most interesting comment was delivered by Nigel Farage. The vote had represented not only a victory against an undemocratic and faceless bureaucracy in Brussels but ‘against the big merchant banks and big businesses’.

Worryingly, neither the majority of the Brexiteers nor their Remainer counterparts – at least among the political and journalistic classes – have grasped what the former Ukip leader understood instinctively; that Brexit is in fact a sub-plot in a much larger, overarching narrative: the battle between international finance and the one force that can realistically check its relentless and apocalyptic march – the nation state.

Understand this and we understand the recurrence of similar historical trends that occurred from the end of the 19th century to the outset of the Second World War as well as alignments which on a superficial analysis seem so unsettling: Nigel Farage and George Galloway, the economist Steve Keen, commentators such as Ambrose Evans-Pritchard and further afield those like Marine Le Pen – the strangest of bedfellows. But traditional demarcations are dissolving and new ones can be discerned if instead of thinking in terms of political or economic affiliations we consider psychological ones. The most convoluted Venn diagrams are reconstituted into a simpler, more dualistic architecture: internationalists, globalisers and homogenisers on the one hand and nationalists, localisers and diversifiers on the other.

By reference to these two psychological archetypes the strangest of alliances make perfect sense. How is it that mandarins of the supposed ‘left’, emotional and cultural Marxists with their heavily internationalising political agenda, steer not just processes in Brussels but throughout all the other globalising institutions which seek to make the planet a single, themeless soup? And how is it that their agenda should dovetail so perfectly with the interests of the so-called ‘right’ – merchant banks and big businesses as Mr Farage referred to them – and of international finance in general? The answer is that the Brussels bureaucrat and the Goldman Sachs banker are, on the psychic level, pretty much the same animal. Both create a world in which power and ownership are concentrated (whether in the state or in the giant corporations and banks that service them) rather than distributed. Flip sides of the same coin; materialists to the core; which is of course precisely why history shows how former Marxists invariably make the most ruthless neoliberals. When therefore erstwhile Communist and European Commission head Jose Manuel Barroso becomes non-executive Chairman of Goldman Sachs, the logic is flawless.

Their view of the world is a sheltered, and intensely theoretical one which seeks the elimination of barriers that impede their monolithic goals. The bureaucrat does not want obstruction to the movement of money or people, nor does the banker. The nation, save insofar as it can be co-opted into their service, is an irritation – as are variations in languages, weights and measures, local customs and diversity in general. Coca Cola’s nirvana is a simple world in which only Coca Cola is purchased in a single currency that can be transferred without fetters and is consumed from the deepest ocean bed to Everest’s peak. In the realisation of this banal utopia, the Brussels or finance ideologue becomes like the missionary of old who imagines naively that he does God’s work as he brings civilisation to the jungle but who constitutes in reality the front line of Empire.

But the globalisation so vaunted by EU functionaries, liberal intellectuals, transnational corporations and the banks is being exposed for what it really is: the hunt for economic lebensraum in order to accommodate the growth required to pay down debt and fund interest on loans for the benefit of a tiny rentier class. This was the meaning of Mr Farage’s reference to ‘big merchant banks’ and its direct consequence is the misery of the disaffected Northerner who, among others, voted against the bankers and the austerity they have engendered as much as the Brussels bureaucrats who assisted them.

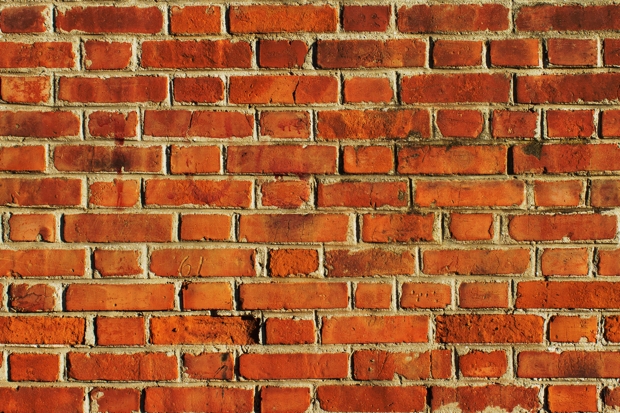

My own hope is that Brexit, if properly handled by people with vision, will initiate a wider recognition of how walls, far from being things to tear down as liberal discourse would have it, represent the natural counter to the forces I have described. It was Charles Darwin’s journey to the Galapagos Islands that taught us the evolutionary significance of separation, or walls. A turtle with a larger bill on one particular island, a smaller flipper on another or a harder shell on yet another, demonstrated how the greater the diversity, the better for the ecosystem as a whole, and for obvious reasons: a single variety of potato, for example, (monocropping), spells disaster if a blight strikes, whereas if we have multitudinous strains then some of them will survive and we won’t starve.

But what exactly was it that led to the rich diversity among the creatures which Darwin studied and the establishment of such plentiful ecological niches? The answer is that which separated them: the ocean in the case of the Galapagos Islands; walls in other words. Everywhere the message is the same. After the Big Bang it was differences in background radiation that enabled the separation and clustering of matter to form galaxies and thereafter life. Had that radiation been uniform there would be nothing. So too the myriad little principalities, kingdoms, republics, city states and nations in Europe which allowed for a constellation of social experiments and the flourishing of so many wonderful cultures where now the difference between England and France is that a Quarter Pounder in the former is known as a ‘Royal’ in the latter. In short, that which separates and demarcates us defines and protects us as well as enriches the whole. Creation could not be clearer: diversity is the sign of life; uniformity the sign of death. Little wonder that, just like the cultural Marxist and the neoliberal, today’s other great globaliser should be the Islamic Fundamentalist with his cult of the grave. The Brexiteer with a brain will only hate Brussels precisely because he loves Europe so much with all its rapidly eroding differences. So too he will be the enemy of the merchant banks and the nihilism of sameness they promote.

The question of immigration is also understood more clearly if one accepts the validity of walls as barriers to homogenisation. People do not want naturally to leave their own countries. They do so en masse only when something is very wrong. Sometimes it is because we have poked our noses into their business and engendered a civil war where they live. But more often than not, mass migration is a symptom of economic malfunction at home. In our own times, this has been occasioned by globalisation, the logic of which compels labour to be as mobile as capital, invariably to the detriment of indigenous workforces whose wages are suppressed by means of such a process in the interests of capital. In short, people who live in countries which have properly functioning national economies will tend not to emigrate. It is the destruction of those national economies solely for the benefit of international capital that has led to one of the biggest gripes of the disenchanted worker who voted for Brexit. The solution to the question of immigration lies in the re-establishment of robust national economies, which in turn will require walls – including capital controls as much as border controls – anathema to the international banker, to the EU official and to all those with Blair-like smiles.

And that is the whole point about excessive migration – it is as bad for the immigrant as for the nation compelled to accommodate him. Olivier Roy’s study of the types of jihadist who drive lorries into crowds reveals a recurring theme: a sense of alienation, how each one of them became disconnected from the mosque of their father and grandfather, from the traditions that had defined their ancestors and had enabled them to develop psychological integration. Rootedness requires feeling comfortable within a dominant culture, a sense of ‘home’, of shared history and destiny, all of which require walls. Cosmopolitanism is the luxury of a minuscule minority who can afford the private jets which make it possible. But isn’t this the language of the fascist and a call for a return to the darkness of the thirties? Perhaps rather a recognition of how that darkness is the inevitable consequence of international capital gone mad and the forces alluded to by Mr Farage; a call to beware. My late mother, who came from Iran and who could hardly have integrated more completely into her adopted culture, put it well: ‘One spoonful of sugar in a cup of tea can, depending upon one’s taste, be delicious but fifty spoonfuls, no matter what one’s taste, is invariably unpleasant.’ This is the language of equilibrium and sanity, not necessarily the goose-stepper.

But walls are essential above all as a metaphor for what Britain and the rest of the world need more than anything else and what the universalising functionary and merchant banker are unable to recognise: limits; to our numbers and our appetites. Simply put, our economic system is predicated on the insane assumption of never-ending exponential growth in a limited world. The refusal of international finance to recognise walls, ably assisted by the politician, the bureaucrat and the liberal intellectual is, in sum, exactly what has got us into this mess and is exactly what oppresses the disaffected Northerner who voted for Brexit, not to mention the vast majority of the planet’s inhabitants.

For the creators of debt, namely the banks, who depend on their debtors’ ability to service their liabilities, the sine qua non is economic growth. Hence the mantra repeated ad nauseam by our politicians: growth at all costs. But while the banker can multiply zeros on his computer forever without reference to restrictions, for those of us anchored in space-time there are genuine limits to the numbers of fish in our oceans, trees in our forests and cattle on our farms. A chasm opens up between the real and virtual economies and sooner or later, in fact now, the Brussels bureaucrat and Mr Farage’s banker come up against that barrier most inimical to their psychology: tactile reality. What happens when a creditor demands an interest rate of 5 per cent while the economy can only grow by 1 per cent or even shrinks as is now occurring? The answer is a transfer of wealth from the debtor – the vast majority of us in other words – to the creditor, or the banker referred to by Mr Farage. Hence the huge and increasing discrepancies in wealth that stoke social chaos.

But our politicians are no better than the Brussels bureaucrat and it would be a fool who kicked against austerity when he voted to leave the EU who then puts his faith in either the Tories or the New Labour elements of the opposition, wedded as they are to the very economic philosophy that oppresses them. Such an understanding can come from the Right just as much as the Left when we disregard outdated alignments and consider the psychological types to which I referred at the outset; one of the more absurd such alignments being the attachment of large elements of Britain’s middle and working classes to the Thatcher years. How little they recognise the significance of that period which, contrary to mythology, did not see a restoration of national pride but an abject capitulation to international finance; an empowerment of the City to the catastrophic detriment of industry and agriculture, or, to put it another way, the triumph of the virtual economy over the real one; of the psychology which does not recognise walls over that which does. All the evidence is clear: where discrepancies in wealth had decreased steadily from the Second World War, they rose again in turbo-charged fashion at the exact point Thatcher and Reagan came to power and neoliberal economics became the norm. Far from a middle class of owners being created, nations of debt slaves were born.

The key then is debt. It is here that the EU’s future – and that of the world – will be decided, much more than at the level of Brexit, although Brexit may well be the catalyst. Our own politicians, just as much as the Brussels bureaucrat and the banker, have been complicit in kicking the can down the street by the expedient of creating ever more borrowings: the grossest irresponsibility towards our children. But they know the truth well enough: those loans can never be repaid; and not just by the Greeks but by any of us. The social injustice and increasing discrepancies of wealth that were behind the Brexit vote will only be addressed with recognition of this fact. Forget Piketty’s increased taxation of the wealthy. Nothing will have greater redistributional consequences than the wholescale repudiation of debt. And so I welcome the day when the debts are no longer serviced and the system collapses. To those who dismiss my radicalism, know this: it will happen. Better then to embrace such repudiation and manage it as best we can to create a fairer social compact.

The greatest problems which face us as an island and as a world stem from the tearing down of walls and the resultant refusal to recognise limits. Walls are good and their reconstruction must begin at the level of the nation.

Comments