Declan Donnellan is riding high. His acclaimed production of the burlesque classic Ubu Roi has confirmed his membership of the elite group of British directors who enjoy renown across Continental Europe and beyond. The critics cheered his French-language production of Alfred Jarry’s anarchic satire when it reached Paris earlier this month. The show, created by Donnellan’s company Cheek by Jowl, is currently bunny-hopping between venues on either side of the Channel. It arrives at the Barbican on 10 April where it forms part of the Dancing around Duchamp season.

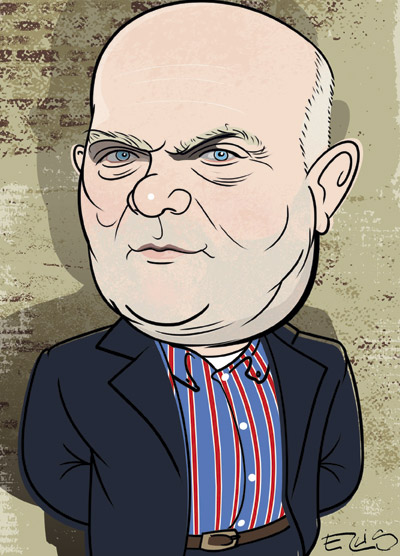

I meet Donellan in a Hampstead café. ‘My local,’ he says as two cappuccinos are clattered down in front us. He’s chunkily built, in his late 50s, with a large, clean-shaven head, a squashy nose and bulbous eyes that shine impishly in a soft, quizzical face. He looks like Socrates reinvented as a racing tipster from Sligo. His voice is a low, velvety purr, full of vitality and warmth.

‘The thing about a great play is that you can never say why it’s great. It’s like writing an obituary. You can make various descriptive attempts, but at the end of the day, the beautiful thing about the person was that they were alive.’

According to legend, there were scuffles at Ubu Roi’s première in 1896. Has its classic status diminished its capacity to shock?

‘First, let’s take apart what happened on the opening night, which has become very mythologised. The play had been in print for six months and there’d been a row about it so everyone knew what to expect, right from the very first word, “mertre”.’ [A pun on the French for ‘shit’ and ‘homicide’.] ‘The audience was tiny, only 100 people in a minute theatre. And Jarry had a tremendous eye for publicity — you think of Rembrandt buying up his prints to inflate the price. He’d arranged for a claque of his friends to shout for the play. But he told them that if others shouted for it, they should shout against it. He wanted the scandal. And he definitely got it. Suddenly he was very famous.’

Donellan tries to explain Ubu’s durability. ‘It sticks two fingers up to French culture. It’s self-consciously crude, with stuff about lavatory brushes and shit, and the language is amazingly dextrous. And it has this bizarre power, which I think is almost magical. And, still, it’s the outpouring of a jokey 12-year-old making up outrageous situations with his friends, then performing them.’ All analysis of art, he goes on, is futile. He’s particularly wary of observations that claim universal scope. ‘Every generalisation is rubbish,’ he says. A moment later, ‘All generalisations are crass.’ He’s often asked questions that invite sweeping or grandiose replies. ‘How would you compare the actors? They’re all different. Is India noisy or serene? Well, both. Are the English cold? Not really. They can be. But the function of art,’ he continues, ‘is to destroy generalisations. Art is always about the concrete and the specific. It is to take the abstract and to give it flesh. It is to incarnate. That’s why talking about it,’ he says, chuckling to himself, ‘is actually impossible.’

Donnellan gets little respite from his work. Cheek by Jowl, which he founded in 1981 with the designer Nick Ormerod, has several productions on tour around the globe. Recently he flitted over to St Petersburg to give notes on a show he first directed in 1997.

‘I don’t do lock-up-and-go. I can’t do the opening night and then not see it again. That’s the European model, to stay in touch. And if someone’s sick, or if someone’s been replaced, or if it’s a big festival, you have to go.’

Donnellan graduated from Cambridge in the mid-1970s and was called to the bar at Middle Temple. ‘The law’s very, very important but you must never confuse it with justice.’ He never practised. Instead he took work as a tour guide and gained experience as an unpaid assistant director. He was 30 before he could sustain himself solely from the theatre. ‘There’s this new thing,’ he says, ‘that it’s only tough now. And that it wasn’t tough then. It’s difficult to counteract because if you do, you get an avalanche of “economic crisis” and “how difficult it is to get a job”. I know. But I don’t remember it being easy. A room in London would always be well over half what you were earning. That hasn’t changed.’

He receives lots of applications from youngsters seeking work experience. ‘They’re terrifying,’ he smiles. ‘Everyone’s got a CV. They’re always doing this in order to do that. And you think, are you going to be double-parked all the way through your 20s and 30s? Aren’t you going to do anything you want to do? How about going on holiday? How about staying up and getting drunk? Scrub that, I’m not that irresponsible, but people are very conscious of their CVs.’

Was he ever tempted to run a large theatre?

‘We’ve have some very nice offers,’ he admits. But the attendant obligations would deter him. ‘Overseeing other people’s work, talking to sponsors, worrying about building funds and rooves. We go to the places where people have invited us. Which is slightly different from running a building with an agenda and an audience that needs to be satisfied.’

They have strong links with Russia. Later this year they begin rehearsing a version of Hamlet with the Bolshoi Ballet. ‘We’re going to write a completely different libretto and use music by Shostakovich. We’ve done workshops in Moscow and we’ve been preparing for it carefully for some years.’ Movement and dance have long fascinated him. He spent part of his childhood in the west of Ireland where dance was ingrained in the culture. ‘The Irish are always considered to be very literary because of the poets and writers, and because of the wit, but there’s another side to Ireland. I remember, as a tiny child, my parents and I would dance when we came together.’ I’m curious to know how much of Shakespeare’s text will feature in his Hamlet.

‘None. People say, “You will miss the word.” And I say, “Nnn-oo. No I shan’t.” I love not having all those words. I love words too. But to have a holiday from words is wonderful. We have a tendency to think the word is paramount. That isn’t true. I feel very much that “In the beginning was not the Word,” as it appears in St John’s gospel.’

He then intones his own version. ‘In the beginning was breath. And then there was movement. And then the Word came quite a long way down the line.’

Comments

A blooming good offer

Join the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting the next 3 months for £3.

CLAIM OFFER 3 months for £3Already a subscriber? Log in