Everybody knows who Joe Biden is, the former six-term senator from Delaware and Barack Obama sidekick. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, the white-haired, bespectacled, 77-year old with the Brooklyn ascent who gave Hillary Clinton fits four years ago, is up there too. Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris have their fans in America; the former is a darling of the progressive movement, the latter was California’s top law enforcement official. Even the young Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of a mid-sized city in Indiana, is getting noticed.

But what about Eric Swalwell, Seth Moulton, and Tim Ryan? What about John Hickenlooper, Jay Inslee, and Amy Klobuchar? And what about that guy named Andrew Wang, whoever he is?

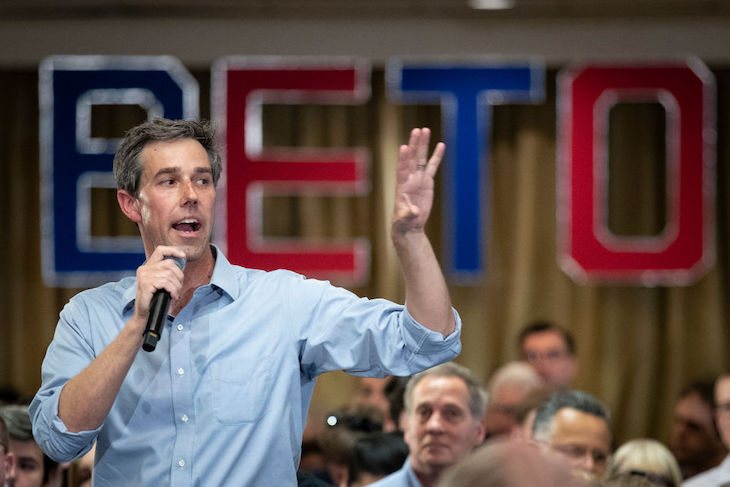

In this phase of the Democratic primary fight, the have-nots are trying their best to turn into a national sensation, like Beto O’Rourke did in the Texas senate race last year. Meeting with patrons in coffee shops across New Hampshire or chatting with farmers in Iowa will only get you so far in California, New York, Wisconsin, and Florida. Candidates nowadays need a viral moment or a breakout segment to get people’s attention, maintain momentum heading into the first balloting, and impress the people who write the cheques. It’s hard for an aspiring president to receive any of this if they fail to meet the qualifications for the first presidential debate this June.

Because there are so many Democrats competing for the same crown, the Democratic National Committee had to set some rules. The party didn’t need to concern itself with these kinds of things in 2015-2016, when the initial crop of five Democratic candidates quickly went down to two. But now, with 21 candidates in the race and possibly a few more to go, order is a must. It’s not like you can put all 21 on the same stage for two hours and expect to treat the voters to a healthy, civil, and informative discussion.

So this year, the candidates must jump through hurdles to qualify for the first debates: they must score at least one per cent in at least three polls or have 65,000 individual donors in their corner. Because the party fixed the number of debate slots at 20, all of the candidates are trying to scrape up small donors in the event all 21 hit the one per cent threshold. Thus, voters have been bothered by constant fundraising solicitations, some gimmicky and others downright bizarre.

To the politicians who are forced to dial or tweet for dollars, this might be a strange experience. This type of fundraising is the polar opposite of the old way of doing business, when all a candidate had to do was schmooze a few multi-millionaires and billionaires during a private dinner and promise very important people that they would be taken care of, in return for a healthy sum. Now, with big money frowned upon, politicians have to show their face to the common man and beg for cash.

Of course, the ends justify the means. The job today is to make the debates and bask in the spotlight of national television for a few minutes. Perhaps those few minutes will result in a breakout moment that powers more donations, media attention, and interest from voters. Perhaps it will result in a dud.

The worst of all worlds, though, is to watch the action from home while asking yourself a million times what you could have done differently to be a part of the action.

Comments