At the start of lockdown, the government was obsessed with how other countries were dealing with the Covid crisis. In No. 10 press conferences, Britain’s daily death toll was shown next to numbers from the rest of the world, putting our handling of the virus into perspective. But when our death toll jumped, the government claimed the calculations were too different to compare and dropped the graph. A few weeks ago, the Office for National Statistics picked up where the government had left off, revealing that England had the highest number of excess deaths in Europe, while Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were in the top eight. The UK had lost the first leg of the Covid race.

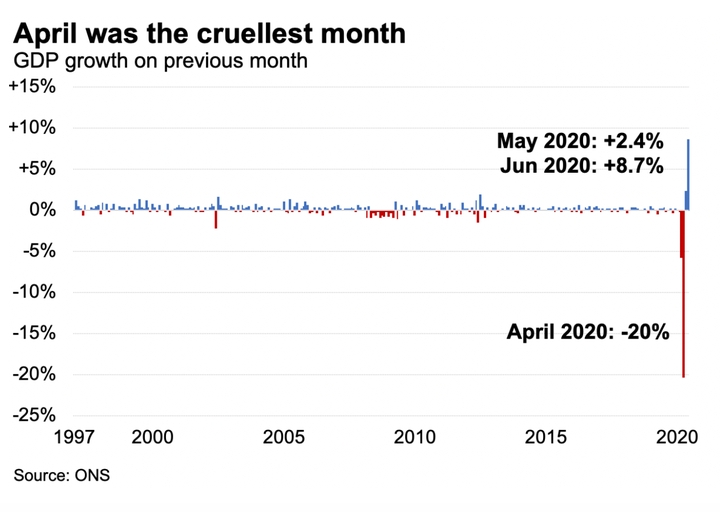

Now it looks set to lose the second: the race to recovery. This depends on two things: how far countries fall, and how quickly they bounce back. We found out the first of these this week. Official figures showed the UK economy contracted a staggering 20.4 per cent between April and June, far worse than the EU average of 12 per cent. The British economy is nearly a fifth smaller now than it was at the start of the year, the consequence of which is fewer jobs, lower wages, lack of options — not to mention opportunity — and a fall in our standard of living.

Every western country has been plunged into recession by Covid-19. But almost no one has been quite as badly hit as Britain. Earlier this year, the ONS published a study which helps explain why: the stringency of lockdown policy correlated to a bigger GDP downturn. As a services-heavy economy, the UK was always going to get clobbered by certain measures, like social distancing. But the decision to live in lockdown longer than other European countries, and with far tighter rules, has left us with our worst recession on record and the sharpest economic contraction since the Great Frost of 1709.

The government can’t control whether the virus returns, but it can control the coherency of its response

Even now, Britain is finding it harder to leave lockdown than any other country in Europe. The Blavatnik School of Government, at Oxford University, publishes a stringency index taking into account nine factors including school closures, work closures and travel bans. It shows that Britain has the tightest Covid-19 restrictions in Europe. This does not bode well for a sharp V-shaped recovery, prospects for which have slowly been forecasted downwards by the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Bank of England. While this week’s data did show the beginnings of a recovery in June, that only brings the economy back to its size just after the financial crash.

There are many other ways to measure a Covid comeback, yet Britain is behind in nearly all of them. About three quarters of French, Italian and German workers are back at their desks, while only a third of the British workforce has returned. Grocery shopping is held up as an indication of retail recovery, yet visits to supermarkets and pharmacies are still down 12 per cent in Britain (they’ve returned to pre-crisis levels in France). Trips to the UK are 28 per cent below pre-pandemic levels, by far the worst figure in Europe. Brits are more likely to be found at home than residents of any other country on the continent, according to mobile phone tracking data.

In contrast, Sweden’s Covid death rate was almost as bad as Britain’s, yet its refusal to formally lock down minimised economic damage: its stock market is now almost back at where it was at the start of the year. But in Britain, the FTSE 100 is down 19 per cent. What’s worrying is that talk in Westminster is still not, really, about recovery. It’s about quarantines, closing pubs to open the schools, and which city will be locked down next.

Preston has joined the list of cities to have restrictions tightened over fears of a surge of the virus. It’s still not clear why, as the criteria for local lockdowns remain a mystery. While the infection rate started rising in the area, only four patients were hospitalised for Covid-19 in the whole of north-west England on the last day for which data is available. If the UK government has an itchy trigger finger when it comes to lockdown, it makes everything harder to predict. Employers have no idea whether they should ask employees back to the office. Shopkeepers in city centres don’t know if they should open their doors. Investors don’t know where or how to invest in Britain’s economy.

Clarity is essential if consumers are going to start spending and companies are going to start hiring or investing. Those who spoke to the Prime Minister in recent weeks say he yoyos on Britain’s lockdown position: anxious to kickstart the economy one day, deeply worried about a new virus spike the next. Yet while a second wave of the virus isn’t guaranteed, Britain is now certainly facing a wave of unemployment. It’s a technicality that the official figure has yet to budge from a record low 3.9 per cent, as a sudden rise in economic inactivity has far fewer people looking for work — why bother, with job vacancies on the floor? Even the most bullish forecasts for economic recovery show employment rates trailing behind: Britain will be lucky if by this time next year its unemployment rate hasn’t doubled.

As well as clarity, people also need confidence to start spending again: the reassurance both that they’re relatively safe from contracting the virus, and also that a sledgehammer won’t be taken to their lifestyle again. The most obvious way to help would be a comprehensive test, trace and isolate scheme. Yet the current system is so broken, NHS representatives actively try to disassociate from it (even though it’s labelled ‘NHS Test and Trace’).

The next three to six months will determine how quickly and effectively Britain’s economy recovers. The government may not be able to control whether the virus resurfaces, but it can control the coherency of its response. Everything that promotes social cohesion, mobility and wellbeing comes from a strong economy, which is why it’s imperative it gets back on track. Britain’s economic downturn may already be consigned to the history books, but the story of its recovery can still be written.

spectator.co.uk/coronomics - Kate Andrews’s podcast series on a world turned upside down by Covid.

Comments