In elections, as in wine, lesser years can still produce good vintages. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown first won their seats in 1983, the year of Labour’s ‘longest suicide note in history’; William Hague’s landslide defeat in 2001 gave us David Cameron, George Osborne and Boris Johnson. The 2017 election is not recalled fondly by many Conservatives. Yet it produced the cluster of ambitious Tories running the party today.

Ahead of the party conference in October there will be a steady drumbeat of announcements

Kemi Badenoch was marked for the top as soon as she entered parliament. ‘It was clear from the start she wasn’t there to make up the numbers,’ says a fellow member of the 2017 intake. She quickly made allies: Lee Rowley, Alex Burghart, Julia Lopez and Rachel Maclean. The quintet now run the Tory party. Rowley is Badenoch’s chief of staff; Burghart her policy brain. Lopez acts as her link to the parliamentary party and the ennobled Maclean is her director of strategy.

The five have been through three parliaments together. First, there was Theresa May’s minority government, in which the absence of a Brexit strategy infuriated Badenoch and her allies. Next came Boris Johnson’s 80-seat majority, in which his big tent conservatism collapsed under its own contradictions. Finally, there was Labour’s triumph, in which the party’s failure to prepare for government quickly became apparent.

Three very different parliaments, but each has helped to form the quintet’s way of thinking. Tasked with taking their party back to power, they are looking to the past for inspiration. Burghart, the historian of the group, is often spotted with a copy of the Thatcherite text ‘The Right Approach’ under his arm. Published in 1976, it declares that: ‘There is no future in trying to find a middle road between folly and common sense.’ It is a sentiment each of the five heartily endorses.

All share Badenoch’s belief in the importance of ‘serious’ politics: each of them quit the Johnson government in protest in July 2022. After the traumas of Brexit and Covid, all five are convinced of the need for fundamental rewiring of the state. Their style is unshowy; one aide notes approvingly the lack of publicity Rowley has received when compared with his No. 10 counterpart Morgan McSweeney. ‘It is difficult to know where “Badenochism” ends and “Rowleyism” begins,’ says one Tory.

Like Margaret Thatcher and then Cameron, Badenoch is launching a ‘policy renewal programme’ to point the way back from the wilderness of opposition. Ahead of the party conference in October, there will be a steady drumbeat of announcements every three to four weeks, signalling shifts in the party’s thinking. The subject of the first this week was net zero. Badenoch declared that Britain’s 2050 emissions target was ‘impossible’. Unlike her debut speech as leader – for which journalists were given 21 minutes’ notice – her announcement felt genuinely proactive, rather than reactive.

Each policy commission will be placed under the auspices of its respective shadow cabinet member. Political control rests with them but outside expertise will be brought in. Frontbenchers have been told to consult ‘wise heads’ from industry and ‘friendly’ thinktanks. Members of the 2017 intake are all too aware of the Tories’ failure to offer significant public sector reform throughout their time in government. ‘Our NHS plan has just been spend, spend, spend,’ says one.

Inevitably, the commission that will attract most attention is that focusing on legal matters. Among senior Conservatives, opinion is hardening on the necessity to advocate withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Rowley told activists last month that he was ‘pretty sympathetic’ to the ‘strong case’ for leaving the Strasbourg court. One Tory MP fears the party risks ‘being outflanked’ by Labour: Jack Straw, Blair’s former home secretary, is the latest to advocate leaving. Badenoch’s allies stress that the ECHR is merely one element in a vast legal patchwork, including the UN’s Refugee Convention. ‘Kemi has never said she was opposed to leaving,’ says one. ‘But that it had to be part of a proper thought-through plan.’

Senior Tories are aware that the words ‘policy commission’ are unlikely to set the world of SW1 alight. But among activists there is a genuine hunger to discuss policy on mass Zoom calls with frontbenchers, after years of being ignored when the party was in government. Even Conservative frontbenchers who did not vote for Badenoch profess enthusiasm. ‘It’s something for us to get our teeth into,’ says one. Although Tories in parliament seem keener than those outside it: former MPs assembled at CCHQ last month were not all impressed at exhortations to offer their services still further.

In an ideal world, work done by the commissions could be implemented quickly once in office. At this week’s Centre for Policy Studies conference, Rachel Wolf, the founder of the New Schools Network, reminded attendees that part of the success of the coalition government’s education reforms was down to preparation. ‘All of the work was done in opposition: the bills were drafted, everyone was talked to, everyone knew what they were going to do.’ Successful schools were therefore able to form ‘a new blob’ to act as ‘a defence against rowing back changes’. The defence held until Bridget Phillipson’s arrival at the Department for Education.

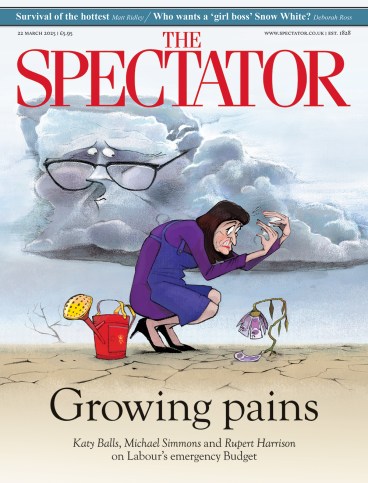

The purpose of the Tories’ policy programme this time around is also to prepare the party for the ‘things you can’t foresee’, in the words one shadow cabinet member. The hope is that when crises come along, proper preparation means there will be minimal ideological disagreement about how best to respond. If policy tensions can be resolved in the privacy of opposition, then public spectacles in office can be avoided. Badenoch’s team believe that Labour’s lack of preparation for government has the party unmoored in the swirling tides of a hostile international climate.

Each member of the shadow cabinet served as a minister between 2019 and 2024. For them, the next general election offers a chance to ‘get things right’. One Tory contrasts the dynamism of Trump’s second term with the failures of his first, suggesting that four years out of office gave his aides the chance to learn necessary lessons. Much as Ted Heath’s loss in 1974 was required for Margaret Thatcher’s triumph of 1979, so too do Badenoch’s supporters hope that the 2024 disaster will tee them up for 2029.

Comments