‘Next time it’s full buggery!’ said Christopher Hitchens as I helped him onto a train at Taunton station after a full luncheon of Black Label, Romanée-Conti, eel risotto and suckling pig.

‘Next time it’s full buggery!’ said Christopher Hitchens as I helped him onto a train at Taunton station after a full luncheon of Black Label, Romanée-Conti, eel risotto and suckling pig. His jaunty remark was overheard by a little old lady standing next to me on the platform. ‘Gentlemen, honestly!’ she said, reaching for the train door. But it was locked. Hitchens stuck his torso out of the window and called to the platform manager to let her in. ‘Too late’, said the uniformed attendant in a flat voice. ‘Stand back from the door, madam’, Hitchens exploded. ‘You’re job is to help this poor woman not to hinder her’, he thundered. ‘Listen to me, you fish-faced, pettifogging baggage man, open this door immediately and let her on the train. What kind of fat-kidneyed cretin are you? Why haven’t you been sacked, you aborted rooting hog, parasite tosser, you…?’ This stream of neo-Shakespearian invective continued as the train drew from the station, and was still faintly audible to those remaining on the platform as the last carriage passed from sight on a bend half a mile down the track.

Neither the old lady nor the station master had the faintest idea who this furious figure was, and yet all the most interesting and memorable features of Hitchens’s larger-than-life personality were plainly manifest in this single episode. He is a courageous, passionate and outspoken defender of human rights, a man of ready wit, rich vocabulary, smutty mind and sharp literary intellect. Born in Malta in 1949, brought up mainly in Portsmouth, and Oxford educated, Hitchens emigrated to America in 1981 and took US citizenship in 2005. The English have been slow to appreciate their home-grown talent. Over here he is best known as a highbrow critic and a left-wing political pundit; and remembered as the shocker who took radical stances over the American invasion of Iraq (by supporting it) and who cast rash scorn upon revered figures like Henry Kissinger, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, Bill Clinton and God. At the same time he has written with admiration of such diverse characters as Leon Trotsky, P. G. Wodehouse, Margaret Thatcher, George Orwell and Rosa Luxemburg.

In America Hitchens enjoys a special reputation, revered as one of their top public intellectuals, treated like a superstar, a regular guest at the White House and, strangely enough, considered a sex symbol. American women have been known to cast their underwear toward him in feints of admiration as he climbs the podium to rail against Islam or the sins of their presidents. If you type him in to Youtube you will see that several of his clips have registered over 700,000 hits, and the internet is swarming with American sites proclaiming that ‘Hitchens is sexy.’ So while the English may be asking themselves if they really need a 400-page autobiography by this man, his American publishers will undoubtedly be signing him up for a sequel.

There is certainly room for expansion, for despite the length and concentration of Hitch 22 it scarcely qualifies as an autobiography. He does not even mention his first wife, Greek-Cypriot Eleni Meleagou, by whom he has two children. His brother, the right-wing, Anglican Mail on Sunday columnist, Peter Hitchens, gets no focus, nor is there a squeak about the infamous public battles that have raged between the two. On his father (a ‘glum’ Naval officer) Hitchens surrenders early, finding himself inexplicably ‘barren of paternal recollections’. After a splendid opening chapter — a rich and thought-provoking essay on death — he turns the reader’s attention to his mother.

Perhaps it is not surprising that he deals sketchily with the horrific events of December 1973 and the ‘lacerating, howling moment in [his] life’ when a telephone call informed him of a report in The Times that a certain Yvonne Hitchens had been killed in Greece. Was this his mother? Yes it was. She had lately taken up with an ex-priest from St Martin-in-the-Fields, called Timothy Bryan, and on 27 November flown with him on a one-way ticket to Athens, where they booked themselves into the King George, an expensive hotel (they had no money), and on the following day, in room 201 on the second floor, they overdosed on the anti-depressant, Tofranil.

Hitchens did not know all this as he flew out from Heathrow. The Times report (which is not quoted in his book) stated that

Mr Dimitrios Kapsaskis, the Athens coroner, said an investigation had shown that Mrs Hitchens had been strangled. ‘There were signs of a fight’, Mr Kapsaskis said.

It seems strange to me that Hitchens did not think it odd when this same Mr Kapsaskis informed him in Athens only a few days later, that there had been no strangulation, no fight and it was a simple case of double suicide. A suicide note proved his point.

Hitchens was shown the bathroom where Bryan’s body had been discovered face down in the tub and was told that he had gashed himself across his chest and throat. Hitchens once told me that, although the bodies had been removed, he saw with his own eyes, evidence of blood all over the bathroom. This too is mysterious. In Hitchens’s Wikipedia entry it is stated that his mother and her lover ‘bled to death after over- dosing on pills and cutting their throats and wrists.’ Where did that come from? In preparation for writing a profile of Hitchens, I secured copies of the autopsy reports on Mrs Hitchens and Mr Bryan. In both, signed by Kapsaskis, it is stated that there were no external injuries to either body.

Perhaps it should be borne in mind that this Kapsaskis was the same forensics man who testified in court in March 1970 that Professor George Mankakis had not been tortured by the government in prison — evidence he was later forced to withdraw; the same Kapsaskis who in August 1970 stated that Eugenia Niarchos had committed suicide, despite evidence of murder (the violent bruises to her throat and stomach, he claimed, ‘were consistent with crude and old-fashioned efforts to revive her’); and the same Kapsaskis who is portrayed in the Sixties’ cult classic, Z, as the corrupt coroner who lied to protect fascist police who broke a politician’s skull by clubbing him from a passing lorry.

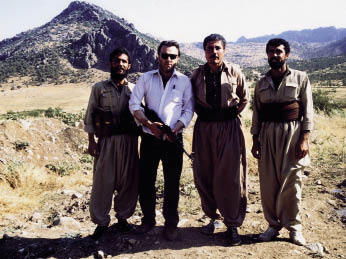

Well, maybe it no longer matters whether Mrs Hitchens was murdered while trying to revive herself from an overdose, or whether she died as she had originally intended, but it was certainly easier for Kapsaskis to bury the strangulation theory and deny the blood. Greece was in turmoil. With anti-government rioting and tanks out on the streets, he had other matters to attend to. Hitchens, too, while he was out there ostensibly to bury his mother, seized the opportunity to interview government torture victims:

With Yvonne lying cold? You are quite right to ask. But it turns out, as I have found in other ways and in other places, that the separation between personal and public is not so neat.

And herein lies the key to this book, which is not really an autobiography so much as a fascinating account of the influences — political, cultural and philosophical — on Hitchens’s intellectual development. His first wife and his brother hardly get a look in not because he doesn’t care about them, but because, in his view, they had no influence on his thought. On the other hand, he devotes whole chapters to his friends James Fenton, Martin Amis and Salman Rushdie (all first-class portraits) and gives illuminating detail on his relations with Isaiah Berlin, John Sparrow, Maurice Bowra and Tom Driberg among many others.

At times he startles with his frank admissions. He explains how he lost his virginity to a stalker at university, participated in mutual masturbation at prep school, was asked to leave the Leys School in Cambridge after a scandal involving another boy. He describes, with obvious relish, a visit to a seedy brothel in New York with Martin Amis, the composition of dirty limericks with James Fenton and a bottom-spanking from Margaret Thatcher. If there is more to tell — about Driberg, perhaps, or his brother — things will have to wait for another time, for there is plenty enough to chew on here. It is a funny, sad, incisive and serious narrative which offers an eye-opening account of the last 40 turbulent years of political history, mixed with tender and often bawdy portraits of some of the more fascinating characters who played their role in making Hitchens the man he is today.

The only regret is that the English have allowed him to slip off to America and be worshipped as their own sexy intellectual icon. He is our son and one of our most gifted writers. We should take pride in that and be busting our guts to woo him back.

Comments