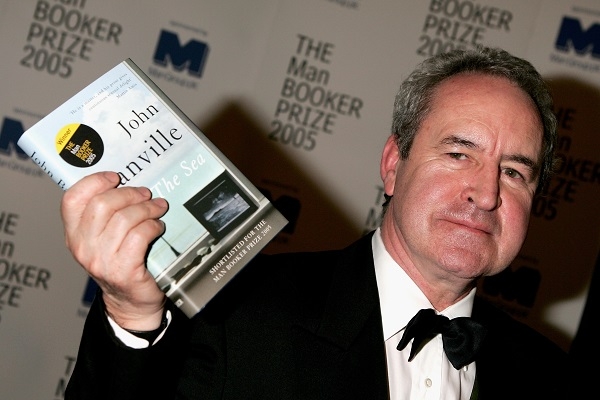

The salubrious surroundings of the Waldorf Hotel seem like a very apt setting to interview a master of style and sophistication. When I arrive in the lobby, John Banville is nowhere to be seen. Peeping into the bar, I notice a grey haired man with a moustache, wearing a tuxedo, softly playing a grand piano. Taking a seat, this strikes me as the kind of place that Alex Cleave would enjoy a drink.

Alex is a semi-retired actor, and the central protagonist and narrator of Ancient Light; a novel that recalls a passionate love affair that took place over fifty years ago. The object of Alex’s desire was Mrs Gray, his best friend’s mother, who was 35, when he was a naïve 15-year-old boy.

When Banville finally turns up, I begin by asking him if this tale is based from any wild sexual escapades he might have experienced in his own teenage years? ‘I wish I’d had a Mrs Gray when I was 15, I certainly didn’t,’ he says with a wry smile.

As an adolescent growing up in Wexford — on the south east coast of Ireland — in the early 1960s, Banville says casual sex, as portrayed in his book, was a very rare commodity.

‘We were very innocent sexually. There was very little sex, particularly any serious, penetrative sex. But I feel I had quite a sexually active adolescence. Kissing was just amazing: two people of the opposite sex, putting their mouths together, it was extraordinary. I suppose I never got over that.’

Banville attended St Peters College in Wexford, an institution that seems to have made little impact on him, intellectually or otherwise.

‘The place was supposed to have been a hot bed of pedophilia, and homosexuality, and I suppose it was. But we just thought it was funny. But the priests I dealt with, most of them were good, decent men.’

Soon Banville is lambasting the Catholic Church, whose methods of obtaining power, he says, worked through ‘inculcating fear and terror in the young.’

Despite this, he’s not convinced that liberalism has achieved much good in Ireland since.

‘I’m not sure freedom is a very good thing anyway. I look around me now in Dublin, and I see these poor drug families: third and fourth generation of unemployed, pushing their children around in buggies. Their lives are destroyed, and I think, maybe the church should come back, maybe we should terrorize people into living better then they do. That’s the sort of thing you being to think of when you are 66,’ he says sardonically.

When I probe him on his last point, he shrugs his shoulders, waiting for his drink to arrive, which seems to be taking an eternity.

‘I don’t know. I can only say what I feel from what I surmise about people. I don’t understand people. That’s probably why I write novels. Not to try and understand them, but to express my incomprehension.’

Unlike his meandering, poetic prose, in conversation, Banville takes the opposite approach. He is succinct and direct, quickly finishing each sentence with little room for digression or elaboration.

The waitress has now returned with a glass of champagne. ‘I ordered Chablis. Oh it doesn’t matter. Champagne will be hell, but I’ll drink it,’ he says.

Death is a subject that haunts both this novel and indeed much of Banville’s other work. His characters — often-lonely megalomaniacs — spend considerable time engrossed in contemplating what lies beyond: when consciousness finally comes to a halt. Creating art, he says ‘is an edifice built against death.’

It’s a subject that he has become increasingly comfortable with, as each passing year rolls by.

‘When you are young, death is this terrible black creature standing by your shoulder. As the years go by, you realize death is just the end of your life, it’s not mystical, or a big thing. But it’s also a great force in life. Death is what gives the savour and the colour to life. Because our awareness of death means that we live much more intensely.’

The living that we partake in, Banville believes, is often recreated in our minds, but not in the present moment. The past is a leitmotif that runs consistently through all of Banville’s work: an obsession that haunts him, yet one that he cannot seem to fully understand.

‘I don’t think that we really remember things, and neuroscience nowadays is backing this notion up. But I think it’s more likely that we make models of the world, that’s what we carry with us into the future. That’s why when you go back to a remembered room, everything is slightly different, it’s because the models have decayed in our brains over the years, and we are visiting something. It’s not a memory, but imagination.’

‘And imagination is much stronger. What fascinates me about the past — and I’ve said it in each book that I’ve written — is its vividness. Why is it so intense?’ he says, looking generally perplexed.

I mention to Banville a conversation I had recently with the American novelist Richard Ford — a good friend of his — who described writing about the darker things in life as an act of optimism. Does he agree with such sentiment when applied to his own work? To a point, he says, but he would substitute the word optimism with faith.

‘Optimism and pessimism don’t mean anything to me. There is no point in being optimistic or pessimistic, that would be ridiculous. One simply accepts the world the way it is.’

What about progress or enlightenment: aren’t these the ideas one strives for, to create art in the first place? Banville is not convinced.

‘In certain areas, like technology, yes there is progress, but that doesn’t mean we progress. We are still the primitive creatures that we were in the caves.’

I’ve noticed that a smile is starting to appear in his face for the first time in our entire conversation.

‘Take a bunch of sophisticates from London, Dublin, New York, and put them on an island, without food for three days. Then you will see what progress is.’

Ancient Light by John Banville is published in paperback by Penguin

Comments