Here is a paradox. Study the photographs of the flats and houses being sold in London’s prime property boom and you see one minimalist interior after another. The huge, empty sweeps of marble and limestone, broken only by a solitary painting, might give you the impression that it is fashionable to declutter your life. One can imagine one of those H.M. Bateman cartoons portraying the shock and horror generated by the man who placed an ornament on his mantelpiece.

Why, then, if we are so keen to get rid of all the clutter, has the price of luxury goods mushroomed over the past decade? Chinese ceramics, the collectable sort, that is — are up 83 per cent, jewellery up 146 per cent, art up 183 per cent. Antique watches – yes, at a time when high-street sales of watches are plummeting due to people using their phones to tell the time instead — are up 83 per cent. Coins and stamps, which you might imagine to be the preserve of dusty provincial museums, are up 225 per cent and 255 per cent respectively.

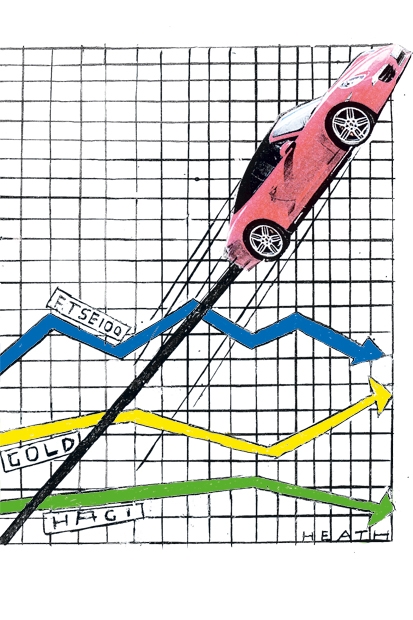

Strangest of all, in some respects, is the boom in classic cars. Never mind that the wealthy are increasingly living in urban apartments with miserable underground car parks rather than country houses with coach houses. Never mind the fashion for hiring Zip cars by the hour rather than owning our own vehicles and all the fuss that goes with them. Cars have become the investment bubble which inflated while few of us were really looking. Prices of classic cars, according to the Historic Automobile Group Index (HAGI), are up 430 per cent over the decade. Forty-six per cent of that rise has come in the past 12 months.

There might be a little qualification needed here. Unlike some classic car magazines, the HAGI index isn’t interested in the rusting Ford Corsair in your garage, which may or may not have increased in value over the past 12 months. As an example of the sort of motor that is included in the index, there was a 1954 Mercedes W196, driven by Juan Manuel Fangio in the Tour de France (not the bicycle race) which sold for $29.6 million and, top of the pile, the most expensive car in the world is a 1963 Ferrari 250 GTO which sold last October for $52 million. These are not cars you are likely to bump into in Sainsbury’s car park, nor indeed will you find them on any road. They are far too valuable to be left to the mercy of Ed Balls. Rather they will be found wrapped in cotton wool, or some other preservative, in a billionaire’s garage, or more likely in an air-conditioned warehouse at a Swiss airport.

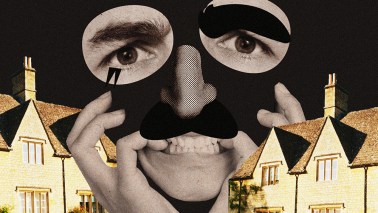

This is the answer to the paradox mentioned at the beginning of this piece: why collectable items have become so sought-after in an apparent age of minimalism. None of this stuff is really to use; it is to put away and enjoy the capital gain, made all the sweeter by the possibility that much of that gain might be tax-free. The boom in luxury goods has arisen partly as a reaction to a clampdown on offshore bank accounts. While the taxman is fast catching up on them, he has yet to get a proper grasp on chattels stored in tax havens, in particular those which are technically in transit as they sit in airport warehouses. Duty may in theory be payable on these goods, but it tends to be at a final destination at which they never arrive.

The ease of storing luxury goods seems to have some influence on which assets have done best in recent years. Cars aside, the best assets tend to be the ones with the highest value to bulk ratio, like coins and stamps. Antique furniture, by contrast, has done poorly, falling by 19 per cent in a decade, according to Knight Frank’s Luxury Investment Index.

There is no obvious way to predict, however, which luxury goods are going to do well and which are going to do poorly. The European Fine Art Fair recently reported a booming year for art sales; the total value of works sold rising to just shy of its peak in 2007. But just because more work is being bought and sold doesn’t necessarily mean that the Canaletto on your wall, or in your warehouse, is necessarily worth more than it was a year ago. Knight Frank’s index suggest that values of individual works of art fell by 6 per cent in the year to last June. The market is exposed to extreme twists in fashion, with much of the big money in recent years being pumped into a few contemporary artists.

Can the boom in luxury goods last? Not at the current rate, according to the Historic Automobile Group, which in January warned that recent inflation in cars is unsustainable. The HAGI index promptly fell by 0.8 per cent in January — equivalent, perhaps, to a wing mirror falling off your Mercedes. It then, however, rose by 3.7 per cent in February. So for now at least the crash has been postponed.

It is hard not to see the rush to invest in luxury goods as a product of economic crisis. It began in tandem with the boom in gold, as investors sought physical assets which would not be affected by a banking collapse (although what happens if one of these Swiss warehouses goes bust has not yet been tested). With an improvement in economies, luxury goods, like gold, suffer from an obvious shortcoming: they are not productive assets. You might gain some income from a classic car rented out as a film-prop, even your old Ford Corsair, a model of which recently featured as Lord Lucan’s getaway car in a recent ITV docudrama. But a car stashed away in deep storage produces a negative income: the cost of storing it and insuring it.

When economic growth returned, and the prospect of further bank collapses diminished, gold duly crashed: from a peak of $1,900 an ounce in August 2011 to $1,300 an ounce now. Yet inflation in luxury goods continued, even strengthened. This is the more difficult paradox to answer: why, when economies are growing reasonably strongly and wealth-creating businesses are generating profits again, do so many wealthy people choose instead to invest in non-productive assets?

Maybe they are slowly changing their minds. One index which might be worth taking notice of is that contained within Knight Frank’s Wealth Report. Asked about their intentions for this year, 31 per cent said they planned to increase their investment in luxury goods, 61 per cent said they intended to hold what they have and 8 per cent said they intended to reduce their holdings of luxury goods. Significantly, 70 per cent said that they intended to increase their investment in stock markets.

All of which might suggest that the trend for hoarding stuff in warehouses might just about have reached its limit. And when markets reach their limit, of course, it is time to worry. Cars, stamps, coins are all sometimes described as ‘safe havens’. Yet over long periods the market for luxury goods has proved more volatile than the FTSE 100. It is all very well looking at indices which have shown an impressive rise, but you need to remember they are based on tiny numbers of sales and can be influenced by the emotions of one or two individuals.

Time, perhaps, to consider putting one of your Ferraris in the catalogue of a high-end auction house before the market shifts southwards back into Auto Trader territory.

Comments