Alexander Alekhine was one of the immortals of the chessboard — world champion from 1927, when in an epic war of attrition at Buenos Aires 1927 he had wrested the championship from Capablanca, until 1935, and again from 1937 until his death in 1946. His victories at the tournaments of San Remo 1930 and Bled 1931 number among the most devastating performances in the history of the game. The historic table and pieces, with which the two titans fought their battles, is a prime treasure of the Buenos Aires chess club.

Alekhine’s forte was the whirlwind attack. His onslaughts were not always fully correct, but the force of his offensives was so intense that opponents tended to buckle under the psychological pressure and burden of analytical calculation, which Alekhine’s fierce will imposed. The following notes are based on those in a new book, Alekhine: Move by Move by Steve Giddins (Everyman Chess).

Rubinstein-Alekhine: Dresden 1926, London System

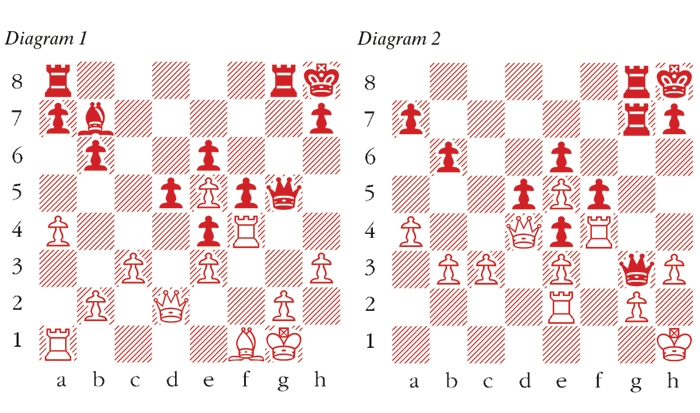

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 Bf4 b6 4 h3 Bb7 5 Nbd2 Bd6 A typically creative Alekhine idea. Taking advantage of the specifics of the position, in this case the inclusion of an early h2-h3, he produces an unusual response. 6 Bxd6 cxd6 7 e3 0-0 8 Be2 d5 9 0-0 Nc6 10 c3 Ne4 11 Nxe4 dxe4 12 Nd2 f5 It soon becomes clear that Rubinstein is in too passive a state of mind, and he rapidly drifts into trouble. 13 f4 g5 14 Nc4 d5 15 Ne5 Nxe5 16 dxe5 Kh8 17 a4 Rubinstein at last starts some active play on the queenside, but Alekhine condemns this move and says White had to seize his last chance to play 17 g3 Rg8 18 Kh2. After the text, that will no longer be possible. 17 … Rg8 18 Qd2 gxf4 19 Rxf4 Qg5 20 Bf1 (see diagram 1) 20 … Qg3 This is a subtle way to gain a tempo, as will become clear. 21 Kh1 Forced, since 21 … Qxh3 was an obvious threat. 21 … Qg7 The king will soon be required on g1, so Kh1 will actually prove to be a lost tempo. 22 Qd4 Ba6 23 Rf2 Qg3 24 Rc2 Bxf1 25 Rxf1 Rac8 Alekhine is relentless in his exploitation of the initiative. As he himself says, Black works with tempo gains the whole time. Now he threatens to win the a-pawn with … Rc4. 26 b3 Rc7 27 Re2 Rcg7 28 Rf4 Rc7 29 Rc2 Rcg7 30 Re2

30 … Rg6 Alekhine’s play nicely combines attacks on all of White’s weaknesses — including, vitally, the e5-pawn. His immediate threat is 31 … Rh6 32 Qd1 Qg7 33 Qd4? Rxh3+! and wins. In fact, the more one looks at the position, the more one realises that White is virtually in zugzwang. For example, the e2-rook cannot move because of 31 Rc2 (or 31 Ref2 Rh6) 31 … Qe1+ 32 Kh2 Rh6 and there is no defence to 33 … Rxh3+. 31 Qb4 Rh6 There is no defence to … Rxh3+, so White has to surrender a pawn. 32 h4 Qg7 Naturally, 32 … Rxh4+ was also winning. 33 c4 Rg6 34 Qd2 Rg3 35 Qe1 Rxg2 White resigns Mate follows rapidly.

Comments