A Western financial analyst based in Shanghai once described China’s economic statistics to me as ‘one of greatest works of contemporary Chinese fiction’. Not even the Communist party’s (CCP) own officials believed them. A cottage industry of esoteric techniques developed to try and measure what was really going on, ranging from diesel and electricity demand to the fluctuating levels of the country’s chronic air pollution, car sales, traffic congestion, job postings and construction – even the sale of underwear or pickled vegetables. One enterprising analyst regularly sent spies to Shanghai port to count the ships and throughput of trucks.

Questioning the official figures has become increasingly dangerous in the China of President Xi Jinping

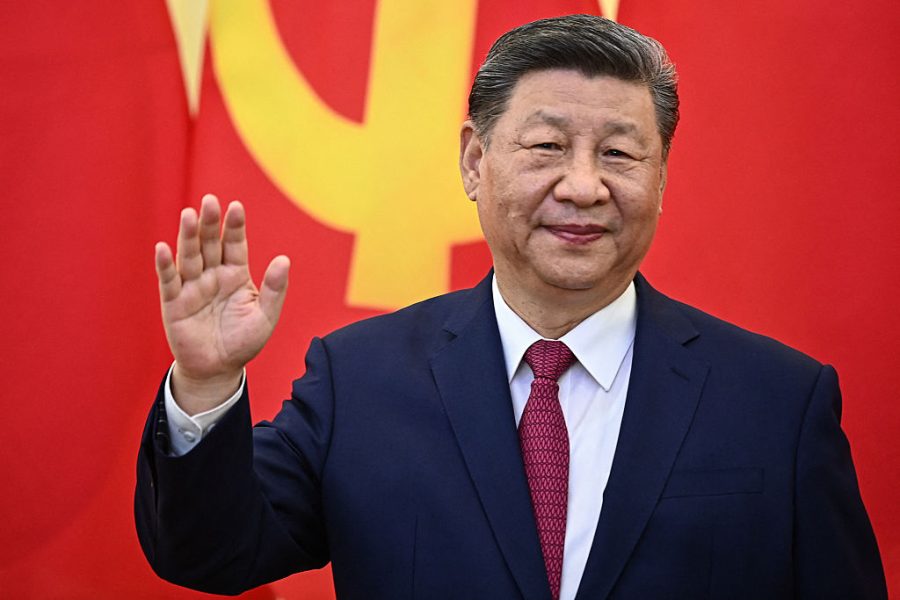

I thought about that conversation again this week when China’s National Bureau of Statistics published new figures claiming that the economy grew by 5.2 per cent in the three months to the end of June and thereby ‘withstood pressure and made steady improvement despite challenges’. Growth figures have always been political rather than economic in China but have become even more so as Beijing seeks to demonstrate that its economy is resilient enough to withstand any further tariffs that Donald Trump might throw at it should their fragile trade truce break down.

I have no idea what new techniques the hapless Shanghai analysts are now deploying, but questioning the official figures has become increasingly dangerous in the China of President Xi Jinping. Shortly before Christmas, Gao Sanwen, a top economist and former official at China’s central bank, cast doubt on official figures, telling a conference in Washington DC that China’s growth over recent years was likely just 2 per cent, which is less than half what the government had claimed. Gao then promptly disappeared from view. Online commentaries in which he had also highlighted soaring unemployment, China’s ‘dispirited youth’ and ‘disenchanted middle-aged’ were deleted by censors. A few months earlier, Zhu Hengpeng, a top economist with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Institute of Economics also disappeared after making disparaging remarks about Xi Jinping’s economic stewardship in what he thought was a private online chat group.

It is more difficult than ever to tell what is really going on with the Chinese economy since the CCP has effectively criminalised pessimism. The Ministry of State Security, its main spy agency, has declared that gloom about the economy is a foreign smear and that ‘false theories about “China’s deterioration” are being circulated to attack China’s unique socialist system’.

It could well be that China’s economy did get a bounce in the three months to the end of June as factories ramped up production and pumped out more exports in order to beat any future tariffs. The government has also attempted to boost consumer demand with a trade-in programme worth an estimated $42 billion (£31.3 billion) so far this year, covering a range of consumer goods, from washing machines to electric vehicles (EVs), air conditioners, smartphones and tablets. Xi has pledged to ‘fully unleash’ China’s consumers, but retail sales actually slowed in June, with consumers cautious in the face of a continuing property slump and a deteriorating jobs market. Housing accounts for around 70 per cent of Chinese household wealth, and with prices continuing to fall, consumers appear to be in no mood to be unleashed.

Meanwhile, the CCP has begrudgingly acknowledged that the economy is chronically overproducing, notably in renewable tech, such as batteries, EVs and solar panels – though the party will not bring itself to use that term. Instead, it has embraced the term ‘involution’ (neijuan in mandarin), which describes what it sees as unhealthy and self-destructive competition, which it acknowledges is fuelling deflation and undermining growth. What it doesn’t acknowledge is that this is a direct result of its own policies – the enormous subsidies thrown at these industries, which in turn is fuelling global wariness about being the target of Chinese exporters desperate to dump this stuff.

The CCP has set a full-year growth target of around 5 per cent, and by hook or by crook it will hit that, no matter what is really going on in the economy. It is not simply a matter of the Chinese government cooking the books, since creating this particular work of fiction is more complex than that.

The Chinese economy is a surreal organism, which simply can’t be measured by the tools that would usually be brought to bear in other developed economies. The system creates perverse incentives whereby officials at every level are under enormous pressure to manipulate data in order to be seen to fulfil the party’s growth targets, for which they are rewarded or punished. Add to that mix a brewing trade war with America and you are left with statistics that are more political and untrustworthy than ever.

My Shanghai analyst soon found another proxy for measuring economic activity – the throughput of visitors at Shanghai Disneyland. I said that felt a little far-fetched, which he acknowledged, but pointed out that a morning in the company of Mickey Mouse was a lot more fun and potentially more productive than dealing with officials at the National Bureau of Statistics.

Comments