It is a sacred mantra of the business circuit that diverse boards improve company performance. It has apparently been proven in multiple studies by the world’s leading companies such as McKinsey and BlackRock, as well as regulators like the Financial Reporting Council (FRC). The evidence is so irrefutable that one FTSE 350 chair raged that ‘There have been enough reports… statistics and… evidence-based research to stop talking about it and get on with it.’ Another viewed the evidence that diversity trumps any other attribute as so ironclad that he tells executive search firms, ‘I don’t want to see any men. I don’t care if they’re Jesus Christ. I don’t want to see them.’

But does the evidence really show that diversity is the key to business success, or is this a case of confirmation bias – accepting a claim uncritically just because we want it to be true?

When you take off your blinkers and look at the evidence with a clear head, you can see the glaring errors in these widely touted diversity studies. Take the FRC report. Its executive summary claims that ‘Higher levels of gender diversity of FTSE 350 boards positively correlate with better future financial performance.’ But when you look at the actual results, they ran 90 tests comparing diversity to financial performance – and every single one found no relationship. The authors announced a result that just wasn’t there. Yet many newspapers and companies parroted the study’s claims, presumably because they wanted them to be true.

Even when studies do find a correlation between company performance and diversity, it could be data-mined. One McKinsey report claimed to find a strong link between diversity and EBIT (earnings before interest and tax, a measure of profits) using one specific methodology. But a far more natural performance measure is total shareholder return (TSR), as that’s what you actually get from investing in a company; some of the best performing investments, like tech firms, have relatively little profits. And even if you wanted something in addition to stock returns, you could choose sales growth, profit margin, return on assets, and return on equity. But the results go away when you use any of those other measures, or more established methodologies. It’s as if McKinsey ran tons of tests using dozens of performance measures and scores of methodologies, and reported the only one that worked.

Similar problems plague a BlackRock study entitled ‘Lifting financial performance by investing in women’. This study uses dubious performance measures and methodologies, and switches between them in different tests. They sometimes measure performance using return on assets, sometimes employee turnover, sometimes TSR compared to one benchmark, sometimes TSR compared to another benchmark. They choose whatever measure gives the result they want in that particular test.This is the research equivalent of the Red Queen saying in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, ‘Sentence first – verdict afterwards.’

Sometimes diversity studies do find a clear correlation between diversity and actual company performance. But as anyone knows with a clear head, correlation does not mean causation. Many other factors could cause both diversity and performance to be low, such as a company’s industry. Coal mining is a male-dominated industry, and has performed poorly in recent years, but this is due to global energy trends rather than a lack of diversity.

None of this is just academic. These studies are having a real impact on business. Regulators are proposing diversity quotas or targets, or mandatory diversity reporting. Some investors have policies to vote against boards that don’t bring diversity up to a certain level, irrespective of the directors’ other credentials. Executive search firms pitch for business touting how many diverse candidates they include in shortlists for prior searches. They liberally cite evidence that diversity improves performance as a justification, even though this evidence is almost always flimsy. BlackRock is a great asset manager and McKinsey a top management consultant, but neither are research organisations. Their goal isn’t to find the truth, but to release whatever result improves their reputation. Can you imagine a world where McKinsey releases a study which finds a negative relationship between diversity and shareholder value – or even that diversity has no effect on shareholder value? Me neither.

The next time you see a study parading the benefits of diversity, sustainability or any other ‘hot’ topic, you should apply the sense-check of Mandy Rice-Davies: ‘they would say that, wouldn’t they?’

Some might ask if all of this matters. Isn’t diversity a good thing, so the ends justify the means? But there are several problems with this line of thinking.

First, it’s dishonest. No matter how strongly you believe that diversity is a good thing, your defence of it shouldn’t have to rely on weak evidence or cherry-picked studies.

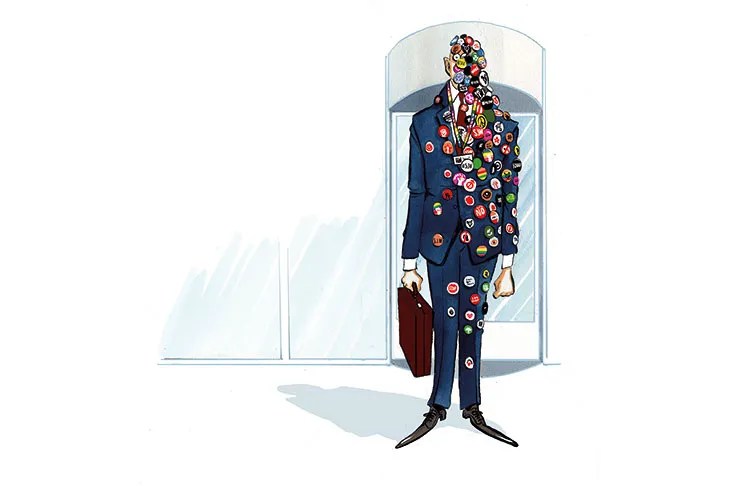

Second, it actually harms the quest for true diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). Diversity isn’t just about gender and ethnicity, but also age, sexual orientation, socioeconomic background, work and educational experience, cognitive style, and personality. These studies suggest that you can ignore the complexity of human life and reduce everything to just gender and ethnicity. But you can see why regulators and investors like the simple message that they can just focus on the proportion of minorities in a company, rather than having to get their hands dirty and examine a company’s culture. My own research gathers a comprehensive measure of DEI and finds that it has no relation to demographic diversity. It also finds that true DEI is associated with higher future financial performance, but demographic diversity is not.

Finally, even focusing on demographic diversity alone, there may be no need to tout a financial case because there are social reasons for pursuing it. Some people argue that you should choose the best person for the job, regardless of their characteristics. But others believe that, due to historic discrimination against minorities, companies should actively recruit from under-represented groups. Perhaps doing so might not maximise profits, but many shareholders and stakeholders will be willing to accept that trade-off — just as consumers buy organic food, despite its greater cost, due to non-financial considerations.

When I brought in black and LGBT entrepreneurs as guest speakers in my class at the London Business School, I did not do so based on evidence that it would boost my teaching ratings, but because I wanted to show business role models to my students. Companies should consider making similar social arguments if they want to boost diversity. This would be much better than telling people to ‘increase diversity because you’ll make more money’ – particular when this is based on flimsy evidence.

Comments