If Emmanuel Macron is elected on 7 May, it will indeed be a true test of the Fifth Republic as De Gaulle envisioned it: a semi-presidential system not necessarily dependent on strong parties to function. So far, this has never really been tested, because the system developed into a de facto two party system. Unless Macron’s En Marche! achieves, in just a few weeks what it took the Socialist Party decades to do – and what no other centrist party was able to – it is likely that he will not be able to rely on a clear majority in parliament. It may have taken 60 years, but De Gaulle’s vision of the Fifth Republic could well be coming to a point of crisis. Whether or not it fails won’t only be down to Macron though. Instead, it will also depend in no small measure on whether, chastened by their historic failure, what remains of the Republican and Socialist parties are willing to cooperate with the centre. But if they aren’t prepared to ditch the sterile power play of alternating centre-right vs. centre-left majorities and compromise, France faces an uncertain future.

Aline-Florence Manent

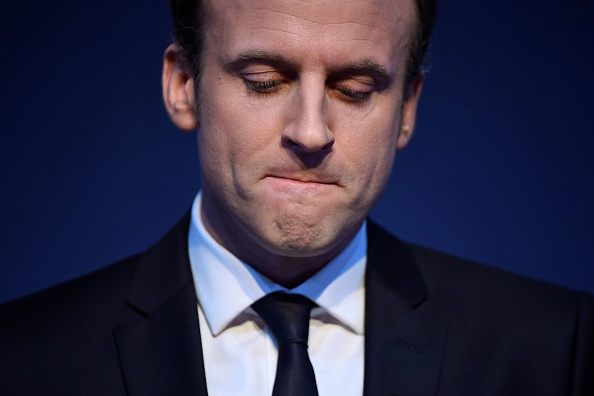

Is Emmanuel Macron doomed to be a lame duck President from the start?

Emmanuel Macron is on the verge of becoming the youngest president in French history. If he is successful in defeating his far-right opponent, Marine Le Pen, it will also be the first time since 1974 that France elects a centrist president. But even in its early days, Macron’s presidency will face a huge test: his En Marche! movement is still very much in its infancy and it is unclear whether it will morph into a full-blown political party before June’s legislative elections. If it doesn’t, one of the main questions that voters will have is whether Macron will be able to govern in the absence of a clear parliamentary majority. Since the term of the presidency was cut from seven to five years in 2002, so that presidential and legislative elections coincide, the president’s party has usually been able to count on a majority of seats in the National Assembly to swiftly pass legislation. In Macron’s case, this is far from guaranteed.

It’s true that the speed with which the mainstream candidates of the right and left, François Fillon and Benoît Hamon, encouraged their party-bases to rally behind Macron for the final round of the presidential race shows that a consensus may be forming behind Macron. Macron, building on his alliance with François Bayrou’s party, the MoDem, and his own movement, might succeed in being able to count on a degree of cooperation from the Republican and the Socialist parties. After joining forces against Le Pen, it is also a possibility that the Republicans and Socialist party will water down their hostility to Macron’s leadership – legislating with the presidential majority, instead of against it, as is usually the case in a bipartisan regime.

But these are big ‘ifs’ and such a situation would be highly unusual in recent French politics. Yet a crisis of the two main parties in parliament does not necessarily bring the whole regime down with it. In fact, De Gaulle was adamant that the fate of the Republic should not be left solely in the hands of ‘these feudalists that we call political parties’. With the help of Michel Debré, he designed the Fifth Republic as a hybrid regime, combining the institutions of a parliamentary system with a powerful presidential office so that a crisis in the party system might not necessarily provoke a crisis of government. This setup was explicitly designed to liberate the executive from the ups and downs of parliamentary party politics.

Comments