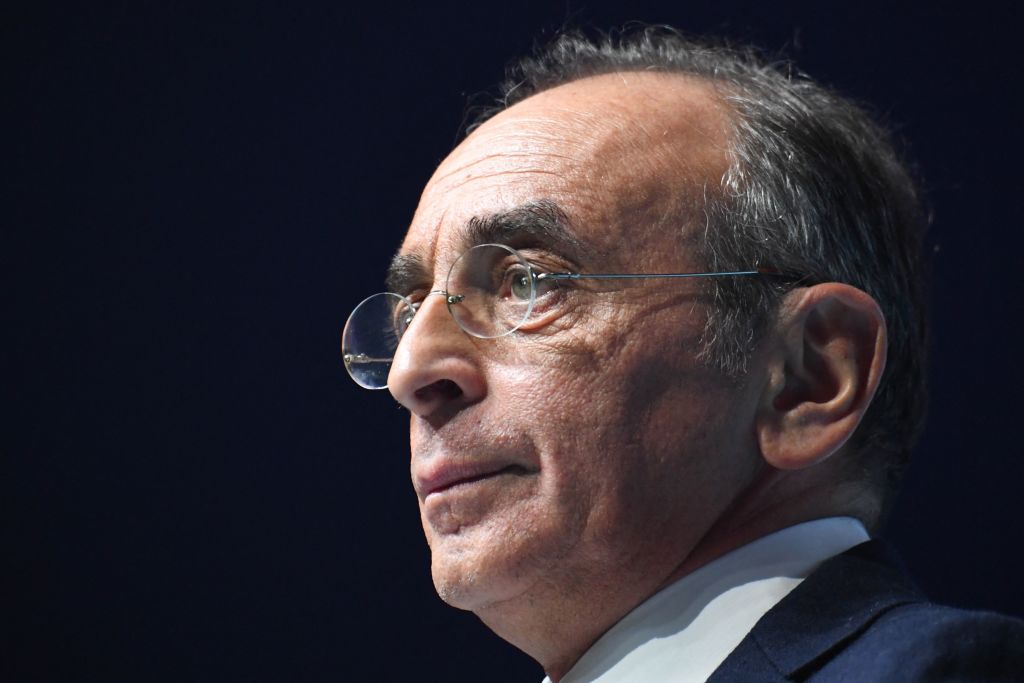

Éric Zemmour is an old-style reactionary France-first politician, a little in the mould of the interwar Charles Maurras. Though unceremoniously blindsided by Marine Le Pen in the 2022 Présidentielles, he should not be written off yet. But this week Zemmour suffered a setback: the European Court of Human Rights rejected his appeal over a conviction for ‘inciting discrimination and religious hatred’ for comments targeting French Muslims. Zemmour’s opponents are celebrating – but the verdict suggests the Strasbourg court can be selective in the rights it chooses to back, and those it doesn’t.

The row stems from a TV interview Zemmour gave back in September 2016, in which Zemmour was promoting a slim volume he had written about what he saw as a conflict between Islam and French culture. Asked what should be done about the matter, he responded:

‘For thirty years, we have seen a process of invasion and colonisation likely to cause a flare-up’.

Zemmour then referred to banlieues on the edge of big cities, such as Paris, where many French Muslims live. He warned that a ‘struggle to Islamise a territory not yet Islamised’ was taking place there. In response to a question about divided loyalties, he answered that Muslims should choose between Islam and France: if followers of Islam thought their faith was not consistent with French values, then, he said, Muslims ‘must detach themselves from their religion.’

At one level, you can see this as a sage decision by an unelected and unaccountable European Court of Human Rights to avoid a clash with democratic lawmakers

For this interview, Zemmour was criminally prosecuted. He was convicted and fined €3,000 (£2,600) under a French law criminalising any words that might encourage discrimination against, or hatred of, any religious or national group.

The French supreme court, to which he appealed, brushed aside an argument that the right to free speech should protect broadcasts of this sort, and upheld the fine. Yesterday Strasbourg, despite a strong argument that the criminalisation of Zemmour had the effect of stifling debate on matters of uncomfortable political and social importance, declined to intervene. The law was clear. Any imperative to protect unfettered political discussion did not apply to to public attacks on Muslims generally, which might cause people to mistrust them or think they held values inconsistent with French republicanism. Prohibiting statements of this sort might limit free speech: but it served a legitimate purpose, and the state was therefore free to do so.

At one level, you can see this as a sage decision by an unelected and unaccountable European Court of Human Rights to avoid a clash with democratic lawmakers. This is something we should generally welcome. But there is still something special about free speech, if only because it is the foundation for any decent democratic polity; and the decision of Strasbourg to butt out of this dispute has some worrying features about it.

First, there are words that do not feature anywhere in the judgment: notably, truth and good faith. Put bluntly, what Eric Zemmour broadcast in 2016 is not the rantings of someone deranged, but – whether true or not – actually quite plausible, and indeed consistent with the perceptions of a good many ordinary French citizens (not to mention sentiments expressed almost every day on Twitter and other social media in this country). If Strasbourg is suggesting that suppressing a good faith opinion of this kind can nevertheless be justified on the basis that it may cause social tension or alienation, then we have a severe threat to open political discourse.

Secondly, there are worrying signs in the judgment that Strasbourg increasingly sees itself, not simply as neutral arbiter between state and citizen, but as an organisation tasked with nudging Europe onto a particular progressive liberal path. Interestingly, the Zemmour judgment incorporates extensive quotes from the Council of Europe’s Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) on the need to combat negative perceptions of Islam and the problem of Islamophobia generally. The ECRI may be worthy: but it is a campaigning organisation. In so far as the European Court of Human Rights sees its views as relevant to the determination of a free speech issue, it is difficult not to conclude that it is straying dangerously close to the line dividing jurisprudence and activism.

Should this decision of a non-UK court concerning events in France, politically very different from the UK, worry us? Unfortunately the answer is yes. It could well directly affect what we are allowed to say and read here.

Take last year’s hate crime legislation in Scotland. The Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021 refers to the need to protect free speech, but does so very much with reference to free speech as defined by the ECHR. The proposals for extending the criminalisation of offensive speech in Northern Ireland go even further. Not only should the criminal law be extended to cover any speech likely to raise animus against, or fear of, particular groups, but free speech should specifically not be protected, except to the extent that the Convention applies.

If the affaire Zemmour is anything to go by (and the judgment very much reflects the thinking of the Strasbourg court in the last few years), any European protection for free speech is likely to be limited indeed in such cases. Prosecutors will find it much easier to take steps to close down inconvenient discussions, not only on Islamism, but on, say, immigration, or race, or gender identity: and it is a fair inference that they will appease activist pressure groups by doing just that.

For the moment, the message for us is clear. Britain needs to develop its own robust protection of free speech, and be prepared to say that this will exceed anything on offer from Strasbourg. Dominic Raab’s proposals in the Bill of Rights to prioritise freedom of speech are a good start. But we need to go further. If ever there is a case where we need eternal vigilance, not to mention pressure on our politicians, it is in connection with our right to say, watch and read what we want.

Comments