Will Michael Gove’s reforms outlast him? They are perhaps this government’s single greatest accomplishment. Within three years it has gone from legislation to a nascent industry, and much of it on display at yesterday’s Spectator education conference, which the Education Secretary addressed. But towards the end, he raised an important point: how much of this agenda is due to his personal patronage? Is the school reform genie out of the bottle? He thinks so. I disagree, and explain why in my Telegraph column today. Here are my main points, with some highlights from yesterday’s conference.

1. The energy and thoroughness of the Gove reforms are remarkable, and go way beyond free schools. A-Levels will soon be set by universities, teachers’ pay and conditions is being made flexible (torpedoing union power). Gove fuses ideas and actions, picks his battles and fights them with grace and elegance. Judging by the anger of the unions and their allies (represented at our conference yesterday) Gove is getting a lot right. When Gove was booed at the Labour Party conference, it was a sign that he’s on to them – and they know it.

2. Free schools: 0.8pc is not transformational. In Sweden, free schools were introduced by a one-term conservative government and survived because the genie was yanked out of the bottle in four years. But in Britain, the figures are rather disappointing. There are just 79 of them, accounting for 0.4 per cent of pupils taught. By the election this may be 0.8 per cent. Those who follow Gove can admire what he has done, but for the vast majority of parents the idea of free schools will be theoretical. If Labour were to end their freedom, not many would mourn. Just as few parents mourned the Grant Maintained Schools which Tony Blair’s government cheerfully slew in 1997. Andrew Adonis was at the conference yesterday saying it would be insane for Labour close a popular school and he’s right. But they wouldn’t close it, just put it under the ‘supervision’ of the local authority. In an interview with House magazine, Stephen Twigg has used precisely this word. Ed Balls didn’t abolish academies, he just neutered them.

3. Profitseeking schools led the Swedish experiment to safety. The charities didn’t expand very quickly, but the profitseeking companies did. They provided the critical mass and the parental affection so the social democrats didn’t dare abolish it when they got back in. Gove has argued that to allow profitseeking schools would be a battle too far – he’s in the business of winning battles, but picking the right ones. And anyway, Nick Clegg has vetoed the idea. This has left British free schools on a slower trajectory of expansion and one that may have looked okay in 2009. But not now.

4. The big surprise: a surge in primary pupils. This has been the game-changer. Early advocates of the free schools agenda (myself included) imagined they would add capacity to a system that was in decline. Pupil number had been falling each of the last ten years, so few extra schools would create a lot of extra choice. Now immigration has changed everything: a quarter of all pupils enrolled in primaries this autumn will have foreign-born mothers. In London, it’s 55pc (including my two kids, so I am contributing to this demographic problem). By the next election some 240,000 primary places will be needed, but free schools are expected to deliver just 8,000).

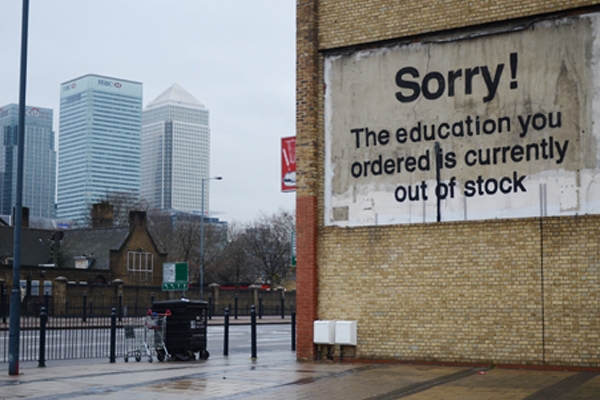

5. Parents hate rejection About 50,000 parents will by this week have been told that the education they want for their child is out of stock, and they can’t get into the first choice of school. The Gove reforms were designed so pupils chose schools, not vice versa. But the slower-than-expected expansion combined with the primary explosion means that parents will find it tougher than ever to have the school place they like. Having 79 free schools is good, but 415 new schools need to open every year just to keep pace with the immigrant-driven baby boom.

6. If Gove’s reforms won’t be noticed by most parents, this makes them vulnerable. Sure, half of all secondaries have academy status right now – but it is by no means clear that this status change will make the slightest bit of difference to the schools. It will lift the schools’ Senior Management Team up a couple of notches on the pay scale, and give them more power. But Gove told The Spectator conference yesterday, it’s a bit like Shawshank Redemption: the academies have been captive for so long they don’t know what to do with their freedoms. It will take time. But the coalition government may not have time: as subscribers to our Evening Blend email will know, Labour is still the bookies’ favouite to win next time.

7. Just because Gove’s reform is right, and helps the poor, does not mean that Labour will not try to kill it. Stephen Twigg is short on policy detail, beyond his ominous-sounding One Nation education. But as long as Labour takes 80 per cent of its funds from the unions, we can rely on them to take their money’s worth. Candidates for the European Parliament elections will just be the start of it.The Labour Party does not work for parents, it works for the unions. The fact that the academies agenda expands an old Blair idea makes Labour want to kill it even more. The party is more a tool of the unions than any time since Michael Foot’s days. The agenda is to restore political control over the secondary education system, and their methods can be brutal.

8. The Baroness Millar effect. Toby Young, Spectator columnist and free school pioneer, asked the conference yesterday to imagine a scenario. Alastair Campbell’s wife and active anti-Academy campaigner Fiona Millar is ennobled, but in charge of education under Miliband and made schools minister. What would she do? In theory, the Academies are on seven years’ notice. In practice, there are loopholes in the contracts that would allow them to be suborned.

9. The slow expansion rate is partly the Treasury’s fault. By refusing to let academy schools borrow, good ones can’t expand. The whole idea of liberalisation is that popular schools open more places. In theory, you would not need new free schools if academies would expand as extra capacity could come from within the system. But not if they’re hamstrung by the Treasury.

10. A Gove Interregnum? He asked yesterday if the coalition’s time in office may be remembered as Cromwell’s six-year Interregnum, full of logical-sounding reform but swept away by the restoration of a previously-rejected regime. It depends when the voters want the restoration. With ten years, I’d say educational reform would be irreversible. Some Tories imagine that in 10 to 15 years, most secondaries will be run by one of a dozen chains (such as ARK, Harris etc). That’s the optimistic scenario. The pessimistic one is that the Gove agenda – like the Baker agenda and the Adonis agenda – is halted by a hostile Labour government.

What Gove has done so far is remarkable, but if most parents won’t notice then his reforms will lack the popular support they need to guarantee their protection. I wish I could believe Gove, that the reforms are now safe but the history of English education reform has been one of false dawns. It is still too soon to say if this one is for real.

Comments