There is, we all know, only one anniversary that matters this year: 20 March 2014, 50 years since The Twilight Zone episode ‘The Masks’ was first beamed into America’s cathode-ray tubes. Bunting will be stretched from television screen to television screen in celebration. Champagne will be spilt over remote controls. After all, ‘The Masks’ isn’t just a particularly fine episode of a particularly fine show. It is also the only episode — of 156, if we don’t count the two revival series made in later decades — to be directed by a woman. Ida Lupino.

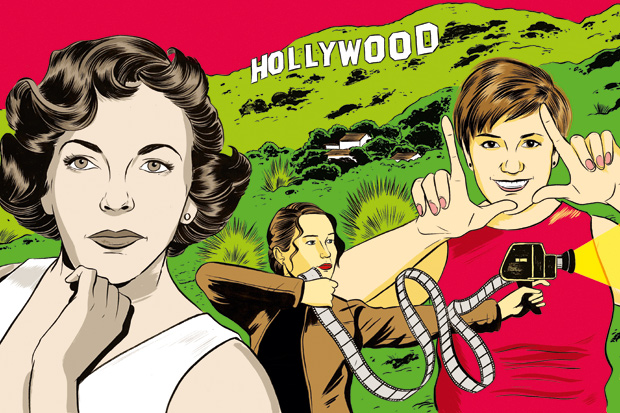

Lupino, who died almost 20 years ago, was a Hollywood pioneer — and not just because of The Twilight Zone. After moving to America in the 1930s, from her birthplace of London, she deployed her acting ability and smoky beauty in numerous films, including a great pair with Bogart, They Drive by Night (1940) and High Sierra (1941). But it was what came next that really marked her out. In 1948, she and her second husband established a production company. Then, starting with Not Wanted (1949), and running through to 1953’s The Hitch-Hiker and The Bigamist, she began to make her own movies from the blank page up. Other women, though not many, had directed before. But Lupino was something that Hollywood had barely even countenanced: a woman who acted, wrote, produced and directed.

‘I didn’t see myself as any advance guard, or feminist,’ said Lupino later. This may seem an odd claim from someone who wasn’t just making films in a man’s industry, but was also making films, such as Outrage (1950), that offered a feminine perspective on the subject of rape — but there is a sad truth to it. An advance guard is, technically, a detachment of troops that treads where the main force will soon follow. Yet, when it comes to female film-makers in Hollywood, that main force is yet to arrive. In the years since Lupino made her last feature film, only one of 60 winners of the Best Director Oscar has been a woman. That 1.7-percenter was Kathryn Bigelow, for The Hurt Locker in 2009.

Last year, however, things felt a little different in Tinseltown. You may have noticed it in the end-of-year reviews, and the names that kept coming up: Lake Bell, Greta Gerwig, Brit Marling; all of them actresses in front of the cameras, but also film-makers behind them. Bell produced, wrote, directed and starred in In a World…. Gerwig co-wrote and starred in Frances Ha. And Marling co-wrote, produced and starred in The East. Never mind the wolves — these gals, and others like them, deserve a freehold on the adjective ‘Lupine’.

The question that hovers over all of this is: why now? Is it that Hollywood’s conscience has finally started catching up with the 20th century, or perhaps even with this century’s wave of hashtag feminism? Or is the answer something more unedifying? I’m guessing the latter. It was probably the $288 million made by Bridesmaids (2011), a comedy by and largely for women, which convinced the film industry’s moneymen that there’s gold in them thar handbags. About half of the cinema tickets bought in the US last year were bought by women, so someone will have put two and two together to come up with ‘Holy Hell, Harvey, we can’t afford to alienate them dames.’

For the sorry truth is that, despite recent advances, Hollywood is still a man’s playground. The New York Film Academy recently put together some figures to demonstrate the scale and nature of the imbalance. Apparently, men outnumber women on film sets by five to one. Only 9 per cent of directors, 25 per cent of producers and 15 per cent of writers are women. When President Obama delivered a speech to the employees of DreamWorks Animation in Los Angeles last November, he said that ‘the stories that we tell transmit values and ideals about tolerance and diversity’. Yeah, shame that the payrolls don’t too.

Perhaps this is a reason to regard the Lena Dunhams and Lake Bells of Hollywood as privileged — and then slaughter them when they don’t, supposedly, live up to that privilege. Indeed, Bell was criticised for appearing naked, save for an artful full-body transfer tattoo, on the cover of a magazine last year.

But it shouldn’t be forgotten that these girls have fought, and are still fighting, against Hollywood’s status quo. Early in her career, Ida Lupino was encouraged to bleach her hair so that she could be sold as the ‘English Jean Harlow’. Nowadays, Brit Marling tells of how she started writing because most of the roles she was offered involved slipping out of her clothes and tripping into chainsaws. Similar stories, 80 years apart. Here’s looking forward to 2094, when the fact that a film-maker is a woman doesn’t even warrant notice.

The question that hovers over all of this is: why now? Is it that Hollywood’s conscience has finally started catching up with the 20th century, or perhaps even with this century’s wave of hashtag feminism? Or is the answer something more unedifying? I’m guessing the latter. It was probably the $288 million made by Bridesmaids (2011), a comedy by and largely for women, which convinced the film industry’s moneymen that there’s gold in them thar handbags. About half of the cinema tickets bought in the US last year were bought by women, so someone will have put two and two together to come up with ‘Holy Hell, Harvey, we can’t afford to alienate them dames.’

For the sorry truth is that, despite recent advances, Hollywood is still a man’s playground. The New York Film Academy recently put together some figures to demonstrate the scale and nature of the imbalance. Apparently, men outnumber women on film sets by five to one. Only 9 per cent of directors, 25 per cent of producers and 15 per cent of writers are women. When President Obama delivered a speech to the employees of DreamWorks Animation in Los Angeles last November, he said that ‘the stories that we tell transmit values and ideals about tolerance and diversity’. Yeah, shame that the payrolls don’t too.

Perhaps this is a reason to regard the Lena Dunhams and Lake Bells of Hollywood as privileged — and then slaughter them when they don’t, supposedly, live up to that privilege. Indeed, Bell was criticised for appearing naked, save for an artful full-body transfer tattoo, on the cover of a magazine last year.

But it shouldn’t be forgotten that these girls have fought, and are still fighting, against Hollywood’s status quo. Early in her career, Ida Lupino was encouraged to bleach her hair so that she could be sold as the ‘English Jean Harlow’. Nowadays, Brit Marling tells of how she started writing because most of the roles she was offered involved slipping out of her clothes and tripping into chainsaws. Similar stories, 80 years apart. Here’s looking forward to 2094, when the fact that a film-maker is a woman doesn’t even warrant notice.

- Lake Bell Photo: Getty

Brit Marling with Diane Kruger Photo: Getty

Comments