Arabella Byrne has narrated this article for you to listen to.

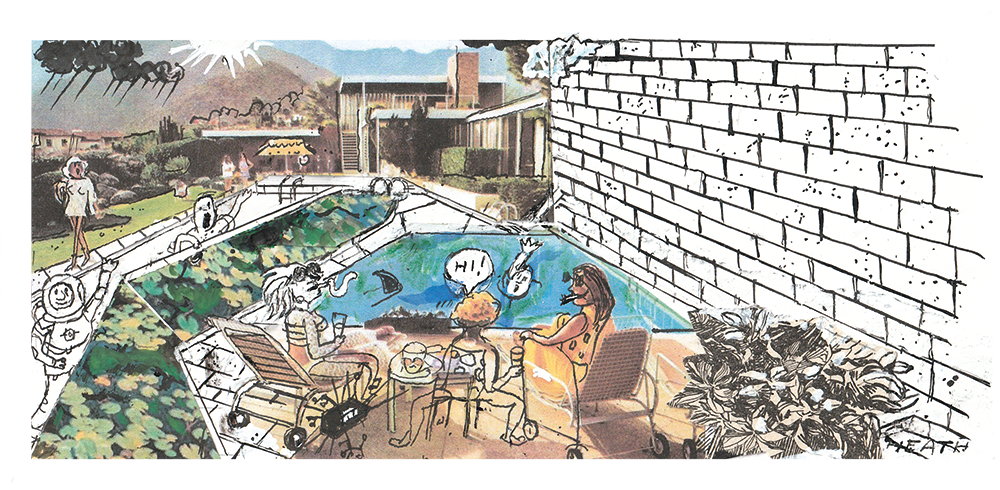

I’ve always loved English swimming pools. I can’t help it – I am a pool-fancier. The lumpy feel of the blue lining beneath pale feet; the peculiar, chlorinated smell of the pool hut where you do the knicker trick; the scratchy pool towel, the near-collapsing deckchair by its side; the greying sky overhead. There’s the swimming, too, but that’s not what gets me. No, the English pool is a particular social idea, a knowing nod to vulgarity, a paradis artificiel in our rainy climes.

Chips Channon, an early adopter, knew it when he insisted on putting in a pool at Kelvedon in 1937, as did Viscount Astor when he went against his mother Nancy’s wishes and did the same at Cliveden. Rishi Sunak, presumably misty eyed about California, put one in at his house in Yorkshire, although his can’t have been a joke.

In the past few weeks, the English pool will have been ‘opened up’ for the season, its strange blue cover winched back anew. In my village in Oxfordshire, the pool man has been furiously circulating in his van, pouring chemicals into these hallowed blue squares. More than the ice-cream van, more than the smell of cut grass, more than the cricketers, it is the pool man that heralds summer to me.

But his arrival presents me with an annual etiquette conundrum. How acceptable is it, really, to ask to use someone’s pool? Is it, as I suspect, by invitation only? In anticipation of a summer well-spent in these pleasure gardens, I poll friends for answers. The response is mixed. ‘My love!’ some shriek over WhatsApp. ‘Don’t be silly – we would love it, bring the children.’ Others give more expansive answers. ‘I’m simply delighted for people to come to swim,’ says one friend, ‘but it must be at my asking.’ A few cite operating expenses as rationale for tolerating intruders: ‘Given that it costs a small fortune to heat the bloody thing, it makes sense for others to use it when we don’t… If you could just let us know when, in case the dogs jump in when the liner is off.’

Mumsnet, with its customary concision, has a special acronym for pool-fanciers: PITAs (pains in the arse). Nearly everyone I asked had some horror story of social faux pas committed on their turf: picnics brought in anticipation of a whole day outing, unsolicited nudity, near-death exploits of daredevil children bombing into the blue, a vicar found swimming unannounced, his dog collar lying beside his pants in a heap. No other invitation involves quite the same social tightrope; no other (formal) invitation involves the removal of your clothes.

All in all, my social instinct remains intact. No matter how hot the day, one must wait patiently for the invitation; no gaming of the social contract will do. There are other ways to have a dip, one may tell oneself: the vogueishness of wild swimming in a river, the charm of a paddling pool, a lake even. But none of these is quite so appealing to me.

One friend tells of a vicar found swimming unannounced, his dog collar lying beside his pants in a heap

I consult Katy Campbell, author of At Home in the Cotswolds and house-hunter to the super-rich, to see if the wealthy still care about pools. ‘What you will see these days is a studied concealment of the pool itself: grass right up to the water, yew trees and shrubbery as a border to give the feel of wild swimming,’ she says. ‘It’s no longer a status feature.’ She tells me that the most stylish thing to do is to put a pool in the walled garden, ‘as a wind breaker but also for privacy’. Hedges, walled gardens, giant yews: could it be that the pool-owning classes are seeking to disguise their pools from fanciers like me? Or, rather, are they trying to disguise them from themselves? Once the ultimate status symbol – all sun-loungers and mosaic tiling plonked in full view – the pool must now resemble something like a pond, its tongue-in-cheek golden age of swimming association dimmed.

Back in the Covid days, when foreign travel was banned and we managed to have a legitimately hot summer, I interviewed the founder of a start-up that sought to rent private pools to fanciers like me. It didn’t take off. It’s easy to blame the fact that before long we could travel again, or that the zeitgeist forgot about pools altogether as wild swimming became a more Instagrammable pursuit – but I think I know the real reason. Like all objects of desire, the social dance of the pool-owner and the pool-fancier can never be transactional or too obvious. It must be fraught, tense and only occasionally satisfied.

My phone pings as I’m writing: ‘Swim with the children later?’ says a pool-owning friend a couple of fields away. I must wait at least an hour to reply. I don’t want to look too desperate.

Comments