When I was 11, I was a pompous little git, but was I also a playground prophet? It first dawned on me that I was one lunchtime in the late 1970s as I looked around at my peers. There they were shouting, swearing and hitting each other. Were we, I wondered, the clueless inheritors of a system we wouldn’t be able to take the reins of successfully? A system that we hadn’t been raised with the discipline to appreciate, or even to understand? Were we doomed to decline? The years since – and the current state of Britain – suggest I was right.

Looking back, it seems clear I was picking up on the doomy declinism of the pop culture of the late 70s; the John Mills’ Quatermass TV series, all social breakdown and ultraviolent youth cults; or World In Action with its melancholic organ theme and grainy titles of riots and swivelling nuclear warheads – allied to a budding conservative temperament. I’m sure about five minutes later I was thinking about Blondie or what I was going to have for my tea. But sometimes I wonder if my child’s mind hadn’t, as children sometimes do, caught at something.

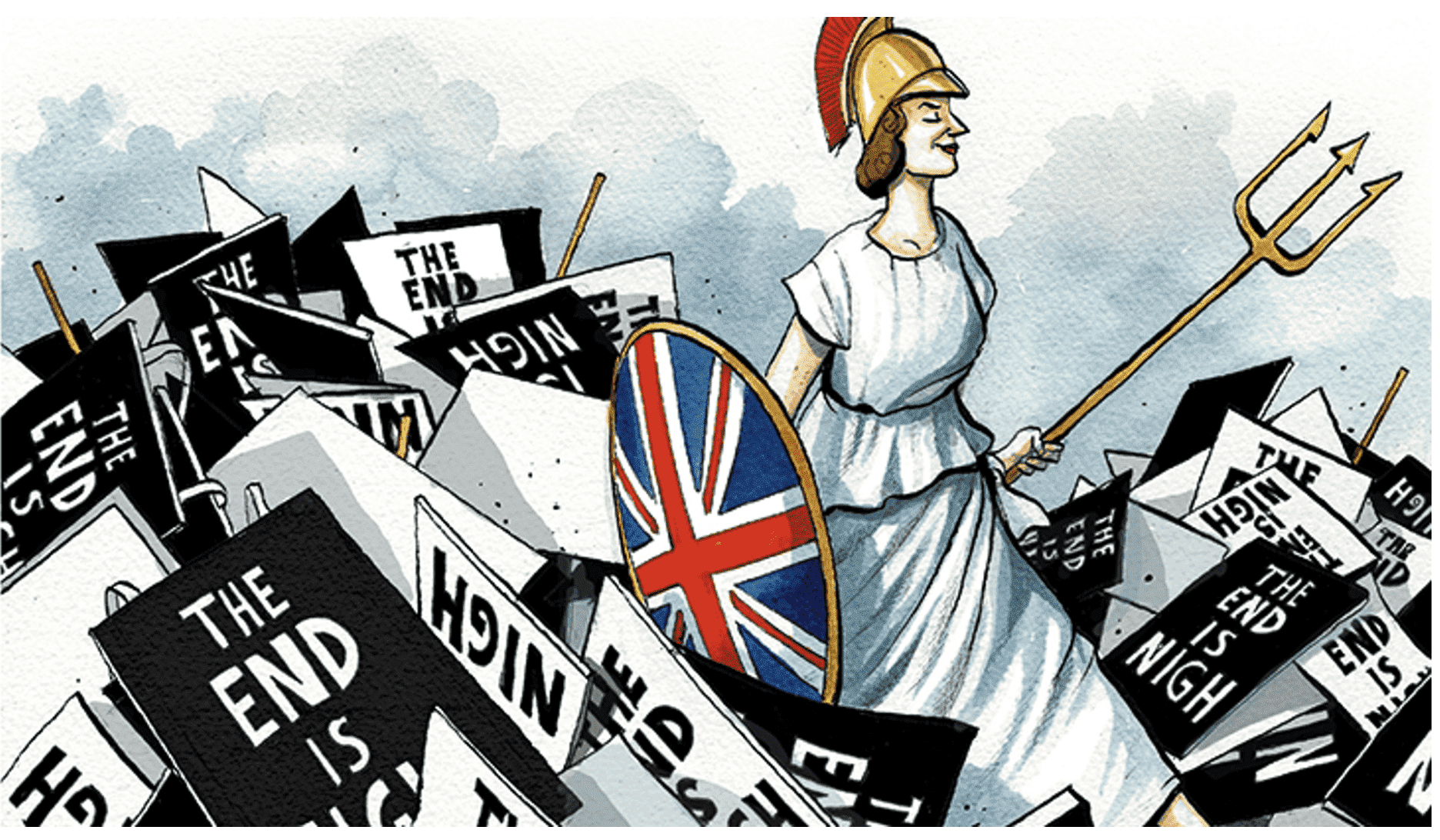

I have frequently found myself wincing at my generation’s progress through life. We didn’t exactly distinguish ourselves in our youth: the best pop group we came up with was a copy of the Beatles with all the fun bits stripped out. We came up with conceptual art and with taking postmodernism seriously. Now we’re the ones in charge, and there is a feeling brewing that we’ve fumbled the ball very badly. There is a looming sense of the world order we inherited, of international stability, commerce and peace, which we took to be just how things are, coming unstuck and exposing us with no plan B.

Many MPs across all sides of the House of Commons seem under par at best, if not spectacularly dense. Imagine, for example, having to explain something slightly complicated to Chris Bryant (born 1962). We produce great gobbets of culture, a simulacrum of what we were handed down. Its main criteria seems now not to entertain people or cheer them up but inspire them. I’m surprised the public can keep the lid on their excitement, they must be so very inspired.

It’s quite possible that claiming society is in decline is simply a sign of becoming a grumpy Horatian old fart

The institutions my cohort now control behave preposterously. The governor of the Bank of England Andrew Bailey (born 1959) squawks about like a panicked hen after an acorn plopped on its head; the police swoop mob-handed on the posters of edgy memes; Wickes, a hardware shop, lectures its customers on LGBT rights. A friend of mine waited 20 hours in A&E at the weekend. My playground peers are now in the driving seat. Going great isn’t it?

Yet some light reading tells us this feeling is hardly unique to our time. Indeed, some of it surfaced in ages now regarded as golden. Roman poet Horace, slap bang in the middle of the renowned reign of Augustus, declaimed that:

‘Our sires’ age was worse than our grandsires’. We, their sons, are more worthless than they; so, in our turn, we shall give the world a progeny yet more corrupt.’

Portuguese glumbucket Fernando Pessoa lamented that:

‘Today the world belongs only to the stupid, the insensitive and the agitated. Today the right to live and triumph is awarded on virtually the same basis as admission into an insane asylum: an inability to think, amorality, and nervous excitability.’

And that was shortly before the ‘greatest generation’ of World War II.

Neither are we gifted with knowing what the future will remember of our culture: the huge popular successes of Martin Tupper and Marie Corelli, which caused such aggravation to Victorian tastemakers, might as well never have happened for all we know of them.

So it’s quite possible that claiming society is in decline is simply a sign of becoming a grumpy Horatian old fart. The trouble is that sometimes there are declines – and somebody is going to be just crossing the line into old fartdom when they happen. It’s not an either/or. You can be a curmudgeon, and correct.

Closer to us, even some of the hard times in living memory already come bundled with a rosy glow. The miners’ strike has translated into a cosy backdrop for heartwarming films such as Billy Elliot and Pride. The 1970s has been reclaimed as a cultural high spot – see the recent Apple TV documentary 1971 – The Year That Music Changed Everything which would’ve been laughable to people then.

There is something people quite like about hard times, at least tolerably hard times, with only a little hindsight. Will our own impending reckoning be an enjoyably nostalgic, even kitsch, aesthetic one day, for someone born in 2011? ‘Remember when everyone had pronouns, eh, and the power blackouts that winter, and you couldn’t get bread’?

Maybe we could try and skip ahead to that stage, look ‘back’ on our grim days, and find some fun in them while we’re still living through them? At least search for some pearls in the dust, as it chokes us.

Comments