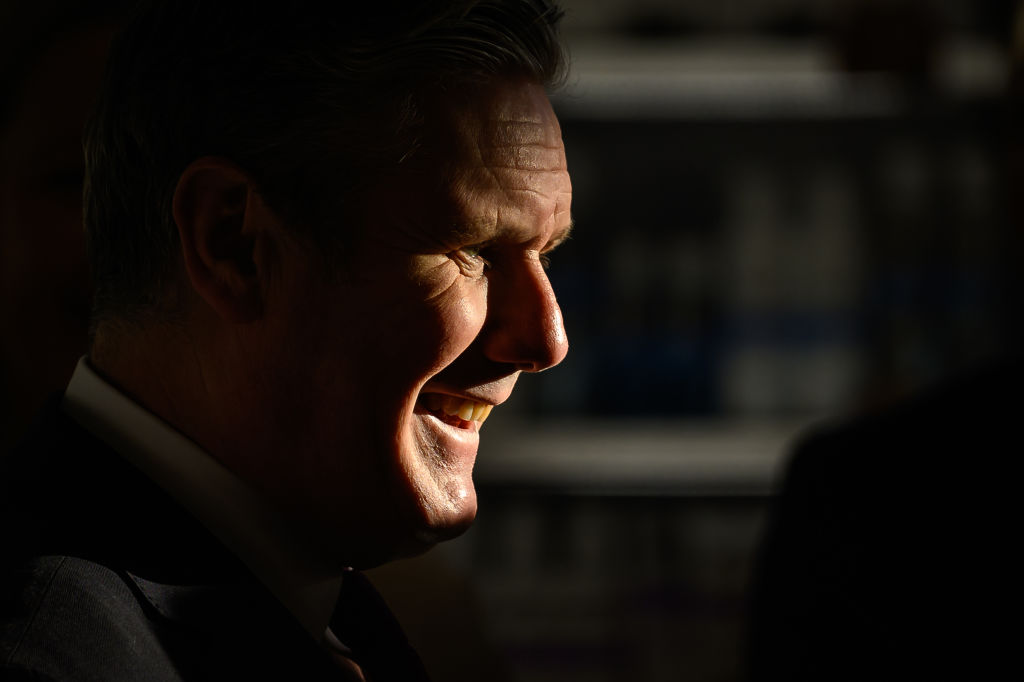

Has Keir Starmer got himself into yet another pickle about what he really thinks?

The Labour leader and his frontbenchers are having to defend a leadership contest pledge he made that he now appears to have junked. They’re obviously used to this, but the latest pledge is on whether parliament should get a vote before military action. It was the fourth of Starmer’s ten pledges back in 2020, which read: ‘No more illegal wars. Introduce a Prevention of Military Intervention Act and put human rights at the heart of foreign policy. Review all UK arms sales and make us a force for international peace and justice.’ That legislation would mean a prime minister could only authorise military action if the Commons gave its consent to a lawful case that was put to it with a ‘viable objective’.

Yesterday Starmer explained that this was about committing British troops to combat, rather than last week’s bombing of the Houthis. He said: ‘What I said when I made that pledge was that what I want to do was to codify the convention.’ The convention he is referring to, in very Starmer-esque language, was the one that sprang up around the Iraq war of a prime minister seeking the consent of parliament for military action even though this is not a formal requirement. The Cabinet Manual currently sets it out thus:

In 2011, the Government acknowledged that a convention had developed in Parliament that before troops were committed the House of Commons should have an opportunity to debate the matter and said that it proposed to observe that convention except when there was an emergency and such action would not be appropriate.

That’s what’s giving Starmer his cover, because the strikes against Houthi targets were considered to be an emergency. But the Cabinet Manual does only say there is a convention for the Commons to debate the matter, not give or withhold its consent.

The question remains whether Starmer really wants parliament to have a vote on military action, or whether that should be the prerogative of the Prime Minister. Even though his leadership pledge was written in Corbynista language, it was hardly a million miles away from David Cameron’s approach when he was in Downing Street. He did not have to hold a vote on action against Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria in August 2013, but he chose to do so because he was worried that Speaker Bercow would force him into it. He wrote in his memoir:

There is no constitutional requirement for a prime minister to ask Parliament before committing British forces to military action. In 2003 we voted on Iraq before the invasion, but in 2011 we voted on Libya only after the first strikes had already taken place. However, I feared that even if I didn’t take the initiative I could effectively be forced into it. While the speaker does not have the right to recall Parliament, I knew that he was quite capable of saying that it needed to happen – putting me in an almost impossible position if I said no.

The following pages document Cameron’s initial confidence, the creeping realisation that he was ‘in trouble’ with the vote, and the way in which he felt fundamentally let down by Ed Miliband, who had initially suggested Labour would support the motion.

Another key line in Cameron’s account of the Syria vote is this: ‘Assuming that other MPs shared this rational patriotism, or naïvety – take your pick – was to let me down several years later, in the vote on bombing Syria when I was prime minister.’ He seemed to assume that MPs would, if given the chance to vote on military action, act as though they had been elected by their constituents to be better informed on their behalf.

Parliament still seems to vote against all military interventions, like it is still atoning for the Iraq war

What happened then and in the years since is that many of them are instead swayed by the weight of correspondence and social media activity, rather than by the arguments presented by the government. Perhaps this is the fault of the executive in the first place for giving the impression of weakness by delegating the decision to parliament, because it then logically follows that an MP would want to delegate the decision to their constituents (even if they don’t on many other matters). Perhaps it is a particular weakness in our legislature, which is not overstuffed with foreign policy experts and which still seems to vote against all military interventions, like it is still atoning for the Iraq war.

But if Starmer does really want his MPs to get the say on whether he, as prime minister, has to commit British troops into combat, then he needs to be realistic about what he might expect from them: they’re less likely to listen to his arguments than they are the emails to their constituency office.

Comments