Every politician likes to say that they don’t pay attention to opinion polls. In my experience, this is almost universally untrue. Those who sail in an ocean of public opinion want to know which way the wind is blowing. The most recent polls show the wind is in the Tories’ sails at the moment: the YouGov post-Budget survey indicated a 13-point Tory lead. But in Scotland for the past year, polls have consistently shown majority support for independence. That’s now changing.

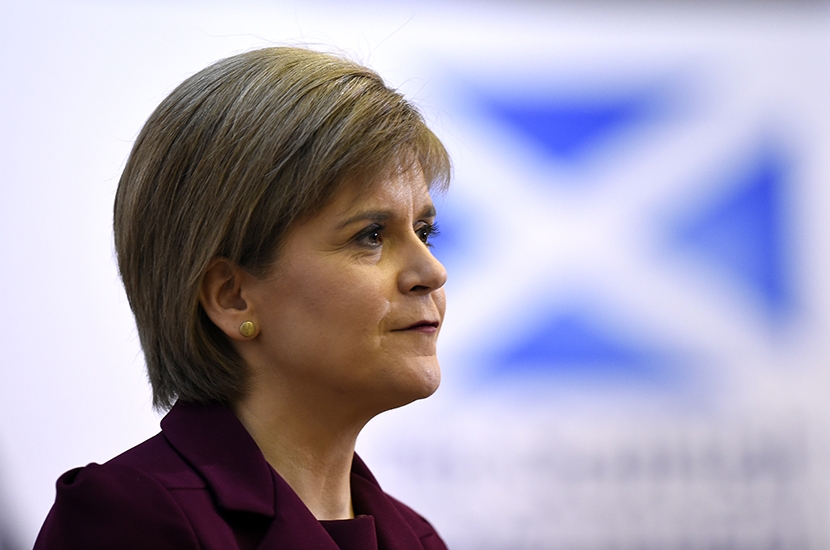

Nicola Sturgeon can’t claim she doesn’t pay attention to the polls; she has too often commented on ones showing independence ahead. After roughly 20 polls in a row put independence in the lead, the Nationalists started to claim that independence was the ‘settled will’ of the Scottish people.

The Nationalists want to try to create a sense of inevitability about Scottish independence. They would like a second referendum to feel like a confirmatory vote rather than a national contest, which is why they used to talk about not holding a vote until support for independence polled at 60 per cent. But in the absence of that, 20-odd polls showing independence at 50 per cent or more seemed enough. That sense has been shaken by these recent results, which at the very least have disrupted the Nationalists’ narrative and boosted Unionist morale. ‘There’s no settled will of the Scottish people,’ one Unionist tells me. ‘It is fluid and fractious.’

Ahead of the Holyrood elections in May, it is important to keep this shift in the polls in perspective. As one figure involved in the government’s effort to save the Union concedes, the results come after Sturgeon ‘couldn’t have had worst press, we couldn’t have had a better story’, referring to the Alex Salmond inquiry and the vaccine rollout. Despite this, the poll which asked about voting intentions for the May elections still showed the SNP winning a majority in the Scottish parliament, albeit of only one seat. It would still be a remarkable achievement if the SNP won an overall majority in an electoral system devised to try to stop any party from doing so and after 14 years in office.

But now it is clear that there is nothing inevitable about a Nationalist majority. Sturgeon doesn’t have the total command of the Scottish political stage that she recently enjoyed and faces a slightly better opposition than she did then. Both the Scottish Tories and Scottish Labour have jettisoned their underperforming leaders — Jackson Carlaw and Richard Leonard — and replaced them with younger, more appealing figures, Douglas Ross and Anas Sarwar. Sarwar, the new Labour leader, looks like a possible future First Minister in a way that the last five holders of his post simply did not. At the same time, the whiff of sleaze around the SNP is growing stronger. Not only are the Sturgeon and Salmond factions duking it out over who is telling the truth, but the party’s chief whip at Westminster, Patrick Grady, has stepped down following sexual harassment allegations.

A fight over whether Scotland is allowed to have a vote on independence would suit the SNP

In the next few weeks the SNP administration in Edinburgh will publish a bill designed to allow them to hold an independence referendum. This is a bit of red meat for their activists, designed to persuade them to overlook what was unearthed by the Salmond inquiry and focus on the wider goal of independence. We can expect the SNP to promise to push on even if Westminster refuses to give its consent (there can be no legal referendum without the UK parliament’s approval). But this tactic cuts both ways. To voters who are unsure if they want another independence referendum straight away, it provides a reason to deny Sturgeon a majority.

Boris Johnson can respond to this by saying he will flat-out refuse to authorise another referendum. If he did, it would play into the Nationalists’ hands. A fight over whether Scotland is allowed to have a vote on independence would suit them. It would be far better for the government to ignore it or simply point out that it is a strange priority at a time when Covid restrictions still mean that Scots cannot leave their local authority area.

If there were to be no SNP majority in May, Scottish politics would start to feel very different. An outright SNP victory has been assumed by so many for so long that even a pro-independence majority combined with the Green vote would feel like a setback. It would undoubtedly weaken Sturgeon’s standing in her party and raise questions about her ability — and desire — to carry on. This would be significant, because much of the recent rise in support for independence has been down to her personal appeal. The Yes side is much weaker without her.

Sturgeon’s own standing has been damaged by the Salmond inquiry. According to a recent poll, only 35 per cent of voters believe she has been entirely honest about the whole business — which is, if anything, generous given that she forgot about a key meeting. The fact that documents are having to be dragged out of the Scottish government by the parliament and that, oddly, there seems to be no minutes of a crucial meeting add to the sense that the government isn’t being straight. The investigating committee complained on Tuesday that it was ‘extremely frustrated’ by the Scottish government’s approach to handing over evidence. More than 60 per cent of voters think Sturgeon should resign if a separate investigation into whether she broke the ministerial code (being conducted by James Hamilton, a former Irish director of public prosecutions) concludes that she did. His findings are expected this month.

Last year was difficult for the Union. As one Scottish Tory admits: ‘For the whole of 2020, even people in my party felt Nicola was having a better Covid crisis than Boris.’ But there are signs that the vaccine rollout is helping the Unionist cause, while some of the sheen is coming off Sturgeon.

Even if the SNP don’t win a Holyrood majority in May, the UK government must not fall back into its old complacency about the Union. ‘After the last referendum, we reverted to type,’ warns one Whitehall hand. ‘We can’t do that again.’ The challenge for Unionists is to make the case anew so that Scottish independence goes back to being as remote a prospect as it was a generation ago.

Comments