At the turn of the century, the ineluctable march of democracy seemed assured. The Cold War extinguished and eastern Europe freed, a Whiggish history of the world continued to be written. A quarter of a century on, the great wave has broken and rolled back. Democracy is not what it was in Chile, Peru, Venezuela, Brazil, Hungary, Egypt, Turkey, Russia and Afghanistan. It has not emerged in China. The future looks less democratic than the past.

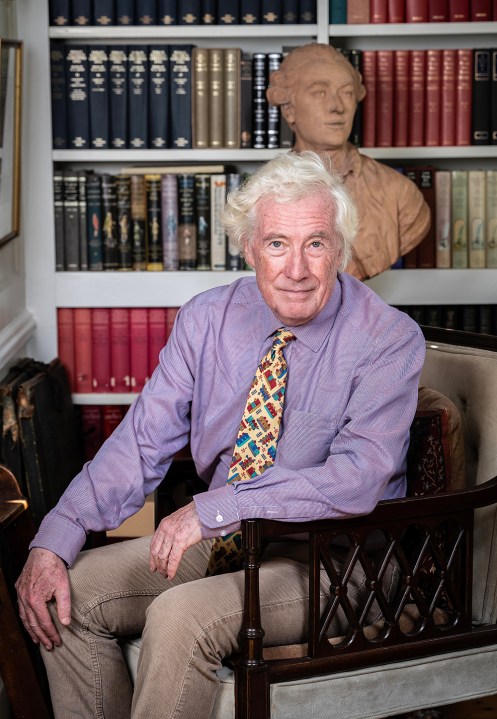

Such concerns bother the big brain of the former Supreme Court judge and medieval historian Jonathan Sumption in his latest brilliant collection of essays. One might reasonably expect him, as one of the great legal minds of our age, to have acquired the high-minded disdain for politics and democracy commonly found in a particular type of contemporary KC. But Sumption has no such snootiness. His is a refreshingly traditional take on the constitution – one which understands, with arresting clarity, the mechanical interdependencies of democracy, politics, free speech, law and rights.

Democracy’s mechanism, he observes, is winding down: ‘I am a natural optimist, but I have to say that I am not optimistic about the future of democracy, in this country or elsewhere in the West.’ He sees it as besieged by economic insecurity, intolerance and fear – and endangered by ever-growing public expectations that the state will fix everything. So it is that democracy ‘needs a coherent defence, not just against those who would like to dispense with it in favour of more authoritarian models but against those who would like to redefine it out of existence’.

Sumption more than provides that coherent defence, setting out how democracy is far better placed than its peers to defend liberty, protect against extremism and offer efficient (less corrupt) government. Nevertheless, he worries that the moral absolutism of the day, seen most readily in universities and publishing, is unlikely to fade quickly. (He is beautifully scathing of the ‘dogmatic intolerance and sanctimonious philistinism’ of the New Roundheads.) So it may be that a tyrannical contingent slowly suppressing free speech and, ultimately, free thought and liberty, will starve democracy of its lifeblood. Should that happen, democracy in the West will not be

formally abolished but quietly redefined, until it ceases to be a method of government and becomes instead a set of political values, like communism or human rights, which are said to represent the people’s true wishes without regard to anything they may actually have chosen for themselves.

Should this happen, the blame will lie, he notes, not just with politicians but with those who elect them.

Sumption is adroitly aware that in the wrong hands the law itself is a threat to democracy. As a non-permanent judge on the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal from 2019 to 2024, he watched in horror as Chinese laws invaded the region. Although never a democracy under British rule, there was latterly some hope that Hong Kong would be allowed to develop into one. That hope has been rudely quashed by the mainland’s national security law. Under its auspices, journalists and others have been jailed for sedition. This caused Sumption to resign last year on the grounds that he could not bring himself to be

part of a system in which respectable politicians may rot in jail for many years for using peaceful, and in my view lawful, constitutional means to advance the cause of democracy.

Democracy and law need each other. Law has many defenders. Democracy has too few

Sumption has also witnessed Strasbourg’s European Court of Human Rights acquire unimpeachable powers that extend far beyond its original treaty. The Court has granted to itself a ‘living instrument’, allowing it to thrust its nose into issues never intended to be within its competence. As it does so, it develops a body of judge-made law that democracies cannot overturn. In his 2019 Reith Lectures, Sumption referred to this as ‘law’s expanding empire’: ‘If we place too many rights beyond the reach of democratic choice, we may cease to be a democracy just as surely as if we had no rights at all.’

This may now be reaching crisis point. The extent to which the court is prepared to push its authority (and luck) was seen starkly last year when it overturned a Swiss law on emissions that had been approved by a referendum. It observed haughtily: ‘Democracy cannot be reduced to the will of the majority of the electorate and elected representatives in disregard of the requirements of the rule of law.’ Sumption is clear: the ideological lawyers of the court will never sanction reform; the UK should quit, incorporate its law in statute and then reform it at leisure. His is an exceptionally convincing case, whose power can only continue to grow with every such judgment.

That our system retains that option reveals an occasional crackle of optimism. Sumption may be clear-eyed about the imperfections of our own constitution but he also acknowledges, with restrained awe, its

combination of resilience and flexibility that… has survived major changes that would have swept away more formal arrangements… We are more fortunate than we realise.

Democracy and law need each other. Law has many defenders. Democracy has too few. We are fortunate indeed to have Sumption making the case for its defence.

Comments