Peter Frankopan has narrated this article for you to listen to.

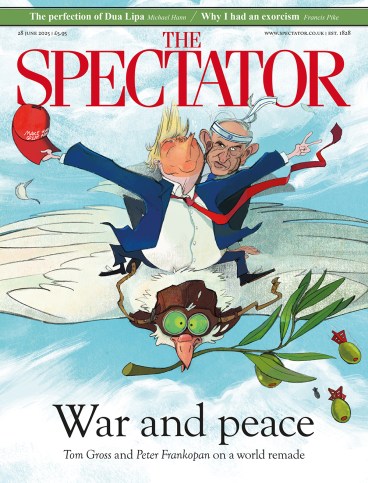

It was clear at the time that what happened on 7 October 2023 would change the Middle East. What was perhaps less obvious was the impact it would have on the rest of the world. In addition to the suffering in Gaza, the weeks and months that followed Hamas’s horrific attacks have seen the reconfiguration of Syria, the effective dismantling of Hezbollah, the decapitation of the leadership of Hamas and now, with Iran, a time when the decision-making in Tehran, Jerusalem and Washington will have a profound effect on the shape of the emerging global order.

Historians like to think about turning points and moments in the past where the wheels of history turned. In one sense that is, of course, true about 7 October. On the other hand, what is perhaps more significant is that what happened that day unlocked a sequence of opportunities that Israel has been preparing for over the course not of years or a decade, but for more than a generation.

It is now clear that Israeli intelligence had completely penetrated Iran’s military as well as its scientific communities before the attacks began two weeks ago. It was therefore not only able to identify its top targets, but where they were located. Many of the most senior figures in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps were targeted, as were their immediate replacements – with the result that there were three chiefs of staff of the armed forces in less than a week.

In some cases, the Israelis were able to work out when they moved and to where; in some instances they even anticipated how they would behave: in the case of the top brass of the air force, for example, one Israeli security official was able to comment that the presence of all senior officers in the same location in an underground command centre was not a coincidence. According to the Israel Defence Forces (IDF): ‘We did specific activities to help us understand things about them and then used that information to make them act in a specific way. We knew this would make them meet, but more importantly we knew how to keep them there.’

It is hard to overstate the logistical complexity of carrying out an operation on this scale, at speed, in a rapidly changing environment. The IDF has been working through a hierarchy of objectives that has been constantly evolving. One reason that so many goals have been achieved is that they have been thought about for a long time. Another is that Iran’s air defences were badly damaged by Israeli air strikes; what was left was destroyed in the first hours of Israel’s assault – so that for the past two weeks, the Israeli air force has enjoyed complete superiority over the skies of Tehran and other major Iranian cities.

The astonishing success is testimony to many years of planning, of surveillance, of careful cultivation of contacts, of embedding agents and assets in Iran. The information-gathering, network-building and forward-thinking were all put in place for a reason; before 7 October, though, it would have seemed far-fetched that the day would come when there would be a possibility of playing more than one or two cards at a time. In fact, we’ve seen the whole hand played in one go.

It is hard to overstate the logistical complexity of Israel carrying out an operation on this scale, at speed

Few would have thought that possible just a few weeks ago. Although the Iranian leadership had been defiant about the progress of discussions with US counterparts about a possible agreement on civilian nuclear power, there was some optimism that the sixth round of talks – scheduled for 15 June in Oman – might lead to an accommodation that would be acceptable to Tehran and to the US. That will have played a role in Israeli strategic thinking, with the narrowing window likely focusing minds on launching a pre-emptive strike 48 hours before talks were due to start.

Some understood that this was the case: just two days before the start of the attack, Iran’s foreign minister, Abbas Araghchi, was at a retreat for high-ranking diplomats just outside Oslo. According to well-placed sources, while there, he was urged by his Saudi counterpart, Prince Faisal bin Farhan Al-Saud, to strike a deal with the US as soon as possible in order to stave off an Israeli assault.

Perhaps the Iranians did not think they were at imminent risk; but something similar happened last week after Donald Trump had said he would wait two weeks before deciding whether to use military force against Iran. Again, the delay in decision-making proved critical. While some reports claim that Trump acted in a fit of pique after his offer to come to negotiate directly and in person, likely in Istanbul, was rebuffed, it was the fact that the US overtures were met with silence that led to the decision to take action. As Secretary of State Marco Rubio put it, the US had said it could live with an Iranian civil nuclear programme, under some strict conditions – but ‘they rejected it’. In fact, he went on, the problem was that ‘they wouldn’t respond to our offers. They disappeared for ten days. The President had to take action as a response.’

In some respects, the lack of communication between the US and senior Iranians is not a surprise. As if the fog of war were not bad enough, the exploding pager operation against Hezbollah last year, combined with the apparent inside knowledge of the movement of key officials, will have meant that messaging would have been slow, difficult and perhaps even impossible: that Trump declared he knew the whereabouts of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and that he would not authorise an attempt on his life, would have been deeply unsettling, regardless of whether it was true or not.

The failure to engage is what Trump reacted to: as Rubio also noted, even as the B2s were in the air heading for Iran, the US President was still considering his options. ‘There are multiple points along the way in which the President has decisions to make about go or no go, and it really comes right up to ten minutes before the bombs are actually dropped.’ Had Iran responded differently, perhaps the facilities at Natanz, Fordow and Isfahan would have been spared. As it happens, the calculus in Tehran had been that bombing was likely anyway – hence the removal of 400kg of enriched uranium and, if reports are to be believed, the tunnel entrances at Fordow backfilled with earth to reduce the impact of the massive US ‘bunker-busting bombs’ that were used in the small hours of Sunday morning.

Not surprisingly, many of the responses to the US intervention around the world were hostile. ‘Each and every member of the UN must be alarmed over this extremely dangerous, lawless and criminal behaviour,’ said Araghchi. Condemnations were also issued by Saudi Arabia’s foreign ministry, by Oman, which called the intervention illegal, and by Qatar, which warned of ‘disastrous consequences’.

What will now follow will require a series of resets that will be extremely delicate

Vladimir Putin expressed his outrage at what he called ‘absolutely unprovoked aggression against Iran’, while Russia’s ambassador to the UN warned that the United States, and especially its leaders, are ‘clearly not interested in diplomacy today’, adding that ‘no one knows what new catastrophes and suffering’ would follow because of the strikes.

China’s response was that Trump’s decision to hit the nuclear facilities ‘seriously violates the purposes and principles of the UN Charter and international law and exacerbates tensions in the Middle East’. It offered its customary anti-Israel spin: ‘China calls on all parties to the conflict, especially Israel, to cease fire as soon as possible.’

What is more revealing than these words of condemnation is how little they have achieved. Russia has shown no interest in bolstering Iran’s position, partly because it has its hands full with Ukraine, partly because it is better to keep the US administration onside than not, and partly because Moscow’s relationship with Tehran – like all marriages of convenience – looks better on paper than in practice. Iran has provided considerable support for Putin’s military offensive, not least plentiful Shahed and more advanced Mohajer-6 drones, as well as hundreds of surface-to-surface ballistic missiles that were supplied last year. That has been quietly and quickly forgotten.

China’s position too has been key, since the status of the Gulf has changed dramatically with Beijing’s economic rise. Just two decades ago, talk of the potential disruption to oil supply would have sent the price of oil soaring and – as happened in 1973 – brought economic chaos to the US, along with efforts to invest in renewable energy to prevent future shocks. Investment in energy in the US (and in oil in particular) has meant America now produces double the number of barrels that Saudi Arabia does every day. The Gulf still matters to the US – as is clear from Trump’s visit in May – but not for its oil, rather for the depth of the pockets of its investors for US businesses.

Ironically, then, it is China that has serious exposure to disruption in this region. Apart from taking an estimated 1.5 million barrels of oil per day from Iran, China depends heavily on the Gulf as a whole for its energy supplies. The costs of chartering tankers to carry crude from the Middle East to China almost doubled after Israeli attacks began. The closure of the Strait of Hormuz, which was widely cited as one of a range of possible Iranian responses to the assaults, would have had limited impact on western markets, but a negative impact on China – as well as on others who import in bulk, such as India.

Iran, of course, has to show it has capabilities and capacity to hurt others, not only in the region, but around the world and also in Iran itself, where the likelihood of crackdowns amid suspicion and fear would seem inevitable. Trump has already christened this the ‘12-day war’. This was a war, he wrote on social media, ‘that could’ve gone on for years, and destroyed the entire Middle East, but it didn’t’.

In fact, what will now follow will require a series of resets that will be extremely delicate. First will be Iran’s realisation that, for all its membership of organisations such as Brics or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, its peers and apparent allies proved reluctant to provide meaningful support when it mattered. Second, the dangers of a ‘Versailles’ moment, where punitive measures are imposed on Tehran, are obvious but not easy to avoid. Much will depend on how strategic thinking in Iran sees the near and medium future, and how those with influence make sense of how one of the world’s great powers in history has found itself exposed.

The most important point is about the return of state-against-state violence, though; of unilateral action by one state against another – and how self-defence and pre-emptive strikes can be blended into narratives that suit those willing to take risks.

We are in an age of intense competition, for minerals, ideas, control and more, where an increasing number of states see that they have a right to reshape the world in their own image. To give just one example, this week, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has raged against Israel, adamantly declaring that ‘as Turkey, we will not allow the establishment of a new Sykes-Picot order in our region, whose borders will be drawn with blood’.

These are dangerous times. Perhaps President Trump is right that the peace he has brokered will be ‘unlimited’ and is ‘going to go forever’. Let us all hope so.

Comments