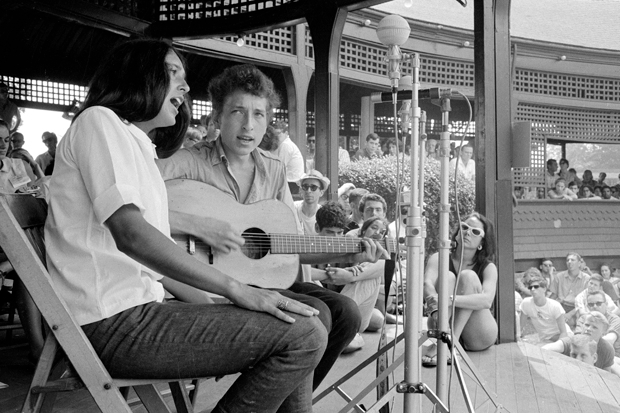

Five songs, only three of which were amplified. Thirty-five minutes, including interruptions. That’s how long Bob Dylan played for at Newport Folk Festival on Sunday 25 July 1965. Even on its own merits, it was a messy, halting set with an inadequate sound system. ‘Why did that matter?’ Elijah Wald rightly asks. ‘Why does what one musician played on one evening continue to resonate half a century later?’

Cameras documented only the stage, and memories are unreliable, so nobody can say how many in the 17,000-strong crowd booed Dylan’s noisy rock’n’roll rebirth, but one eyewitness’s claim that it ‘electrified one half of his audience and electrocuted the other’ is broadly true. Dylan himself was shaken, asking a friend, ‘What happened? What went wrong?’ The festival organisers, led by the veteran folksinger and activist Pete Seeger, saw Eden slipping away. Had Dylan lost his voice that morning and cancelled the show, rock would still have waxed and folk still waned, but Newport turned a trend into a drama.

Received wisdom casts it as a violent generational schism, but Wald, a seasoned historian of folk music and the 1960s, prefers to see it as a still relevant clash between

the twin ideals of the modern era: the democratic, communitarian ideal of a society of equals working together for the common good and the romantic, libertarian ideal of the free individual, unburdened by constraints or rules or custom.

Unfortunately, the road to Newport is too long and much of the backstory is overfamiliar. This is ground that hasn’t just been well-trodden; it’s been steamrollered flat. More illuminating is Wald’s analysis of the folk revival. Far from being a tight clique of earnest fuddy-duddies, it was a vibrantly unstable alliance of different factions, from college-age Peter, Paul and Mary fans to seasoned song collectors, and from old Popular Front leftists to blues purists. Seeger, its de facto leader, was pop as in populist, eager to disseminate his songs of peace and togetherness.

Seeger, who had almost been jailed for defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955, saw himself as the humble servant of a larger cause: ‘The man is nothing; the work is everything,’ as the insightful folksinger Dave Van Ronk put it. To older fans, folk music had kept the left’s flame alive during the dark days of the 1950s and Dylan, the hero of Newport in 1963 and 1964, was its second coming: ‘a link to their own lost youth that validated them and gave them hope for their own resurgence’.

But Dylan was unwilling to be a spokesperson for anybody but himself and anyone paying attention should have known that by July 1965 he was flying the nest. He had already moved into folk-rock with Bringing It All Back Home; befriended the Beatles, the barbarians at the folk scene’s gates; and told the New York Times: ‘I’m in the show business now. I’m not in the folk-music business.’

Wald’s book catches light when it reaches Newport. Armed with dozens of primary sources and eyewitness testimonies, he vividly chronicles the whole weekend and unpicks a lot of enduring myths, but his real contribution to the history of this most divisive performance is not to take sides. He appreciates what Dylan gained and what Seeger lost during a summer when the civil rights and student movements were also fracturing along lines of age and temperament, a process symbolised by the declining popularity of the idealistic Newport anthem ‘We Shall Overcome’ — indeed the whole concept of a united ‘we’.

History has been unkind to the folk revival’s old guard (if they matter at all to most rock fans now, it is only because they nurtured Dylan), but they were nonconformist dreamers, too, and rebels in their time. One newspaper critic wrote of Dylan’s set: ‘What he used to stand for, whether one agreed with it or not, was much clearer than what he stands for now. Perhaps himself.’

Fifty years on, we are surprised when a singer stands for anything more than himself. It’s to Wald’s credit that I finished the book unsure whether I would have cheered, booed or had the wisdom to be ambivalent.

Comments