Brexit is like life. The journey matters more than the final destination. Instead of fixating on where we will, eventually, end up, pay more attention to the things that happen along the way.

As Brexit talks start, there are abundant signs of a possible compromise on Britain’s exit, or at least, on the timing of that exit. Yes, the Article 50 period will, absent an agreement to the contrary, expire in March 2019 and with it Britain’s formal membership of the EU.

But what follows might not look or feel like the clean break that some voters have imagined. Among British politicians of all persuasions, there is, once again, a growing conviction that Britain cannot leap out of the EU in 21 months’ time with just a Free Trade Agreement, or perhaps even just WTO rules to break the fall. A transitional deal is on the cards – assuming the EU27 will agree.

That transition could well look a lot like the European Free Trade Association, whose current members are Norway, Lichtenstein, Switzerland and Iceland. They trade freely with the EU in the European Economic Area. They adhere to the rules of the Single Market and can trade freely within it, but are not part of the Customs Union so they can strike trade deals with other nations. There’s a cost to all this of course, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Britain was a member of EFTA until 1973, and an interesting range of people are now saying it should be again after 2019. Put it another way, when Dan Hannan and Nick Clegg are both publicly saying that a transitional deal based on EFTA is the best course for Britain, there is scope for a sensible, cross-party compromise on what comes next. A leading opponent of a transitional deal has been one Theresa May, who said in her Lancaster House speech in January:

‘I do not mean that we will seek some form of unlimited transitional status, in which we find ourselves stuck forever in some kind of permanent political purgatory. That would not be good for Britain, but nor do I believe it would be good for the EU’.

Instead, she spoke of ‘phased implementation’, a rejection of a single, codified transitional status in favour of a serious of ad hoc subject-by-subject deals with the EU that would take effect at different times.

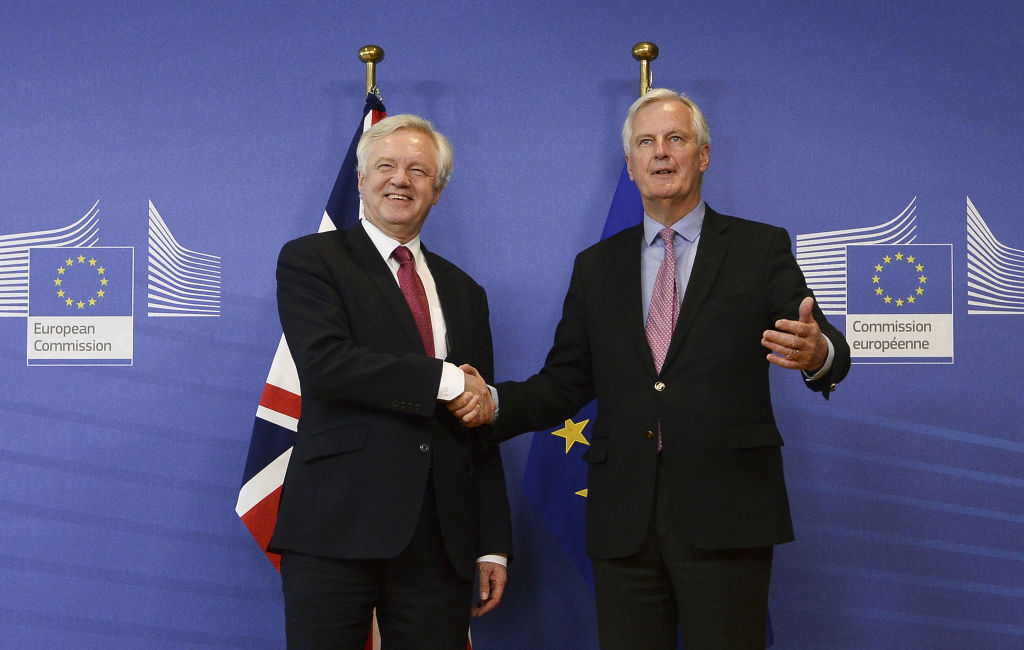

She took that position in defiance of colleagues including Philip Hammond and David Davis, both of whom had been quietly preparing the ground for a more formal transition. Now that Mrs May has shredded her own political authority, ministers such as Mr Hammond are again free to make the case for a transitional deal.

Mrs May’s rejection of that transition was based on the conclusion that EFTA or something similar would not look and feel enough like the Brexit that many voters imagined, not least since it would mean limited, if any, changes in immigration policy, and continued financial contributions to the EU. Because of course, the benefits of EFTA aren’t free. Membership requires submitting to EU rules relating to the Single Market, without much, if any, say on how those rules are set. It requires submitting to the jurisdiction of a ‘foreign’ court, the EFTA Court, which decides on adherence to the EEA rules. It requires paying towards EU structural funds that support eastern EU states, and paying towards central EU programmes and agencies. And it means, more or less, accepting freedom of movement. (It could even mean accepting a more liberal immigration policy than the UK currently has: current EFTA members all participate in Schengen, for instance.) In short: taxpayers’ money still goes to Brussels and Europeans still come to the UK freely.

That, simply, would be tough to sell to voters who voted to Leave the EU in order to stop those two things happening. Which is why the communications work should start now. Time to start preparing the electorate for some tough but necessary compromises.

EFTA membership would not be simple or easy or cheap. It would, as so often in politics, very likely be the least bad choice on offer. But for all its flaws, it would still be a lot better than falling out of the EU onto the stony ground of the WTO rules. The politicians know this, which is why they are, once again, gravitating towards a consensus on how the immediate post-Brexit years should look.

But a political consensus is necessary but not sufficient. The voters need to be consulted and informed. If Brexit will, in the first instance, mean EFTA membership, that fact and its implications need to be spelled out quickly, simply, and repeatedly by people on all sides. Mr Clegg and Mr Hannan both spoke about EFTA on Radio Four this morning in separate interviews; they should be sharing a platform to make that pragmatic case together. (I know a non-partisan think-tank that would be happy to facilitate that, incidentally). Other EFTA-inclined Leavers (I’m thinking of you, James Cleverly) should get more attention.

More broadly, Leavers and Remainers alike should lay down their arms and come together to make the case to the electorate, that a sensible transition is in their interests, while ‘no deal’ is not. As for how long the transitional phase lasts and what comes after: let’s cross that bridge when we come to it.

For now, averting disaster in 2019 should be the priority, and that surely means EFTA, or something that looks a lot like it.

Perhaps this will rile some Leavers, or lead to arguments that it would show Britain’s hand too soon in the Brexit talks. In fact, the EU27 were never convinced by Mrs May’s ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’ bluff even before she was a busted flush. They’ve always known this was the only sensible path for Britain to follow. An EFTA transition is the next stage on the Brexit journey. Time to start preparing Britain for it.

Comments