Rishi Sunak is not wrong to write, as he does in the Telegraph today, that too many young people are being ‘ripped off’ by poor-quality university courses, and that many would be better signing up for apprenticeships. But should a Conservative government really be threatening to tell the universities what to do?

David Cameron’s tuition fee hike was meant to make discerning consumers out of university applicants. Rishi Sunak clearly thinks that’s failed. Cameron allowed universities to charge students tuition fees of up to £9,000 per year (since increased to £9,250). Universities would be able to charge full fees on good quality course, but find themselves having to reduce fees on lower quality courses, with poorer employment outcomes, if not cease offering them altogether.

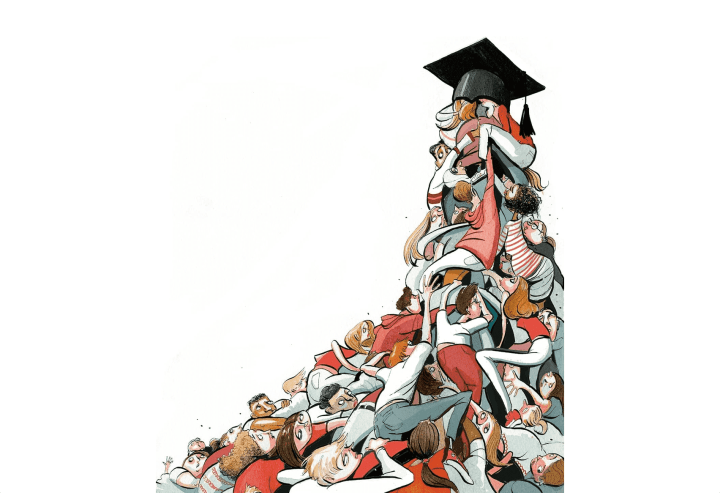

Instead, £9,000 rapidly became the standard annual tuition fee, charged by almost all universities for almost all courses. The quality of many courses remained questionable, with low levels of contact time. Worse, universities used Covid as an excuse to place teaching online, well beyond the period when it was necessary. There remained a horrible mismatch between the number of places available on popular courses and the employment opportunities available at the end.

Why aren’t students studying the data, and using their buying power to squeeze out poor quality courses?

Students can’t claim that the government keeps them in the dark: it publishes data on employment levels and earnings levels, by subject, for graduates five years after graduation. The percentage of graduates in sustained employment or further study varies from 82.2 per cent in the case of creative arts and design to 92.5 per cent in medicine and dentistry (it doesn’t say how many are employed in jobs for which they actually require their degree, or that are related to their degree subject). Median earnings vary between £21,200 for performing arts to £52,900 for medicine and dentistry (so much for junior doctors bleating that they are paid less than coffee shop baristas).

The question is, why aren’t students studying the data, and using their buying power to squeeze out poor quality courses? It is ironic, given students’ reputation for protesting about all manner of things, that so few seem to be prepared to demand a better quality product in return for their £9,250 a year investment. There have been some cases of students taking their universities to court, but it is a wonder there are not mass marches on the country’s senate houses.

Were taxpayers paying for student tuition as they used to, a degree of central planning would be inevitable. In the absence of a market mechanism, the government would have to be involved in deciding how much money to dole out to each university and for each course. A more confident Conservative government, on the other hand, would surely be asking how the market in higher education can be made to work better. There ought certainly to be better incentives for businesses that offer apprenticeships, but as for universities, should we really be clipping their freedoms? Far better to make sure that their customers are better informed about what they are signing up for.

The government should not be laying down what courses universities can and cannot offer. However much we might wince at media studies courses and the like, it shouldn’t be illegal to offer them – it should be up to university applicants to decide whether or not they should exist.

Comments