Follow the Science. The Science is settled. Two phrases which invoke the power of open inquiry to close down open inquiry. Science is not a body of unalterable doctrine, a chapter of revealed truths. Science is a method. It is a means of arriving at the best possible explanation of phenomena through thesis, testing, observation and revision.

Science depends on a culture of doubt, as one of the greatest scientists of the last century, Richard Feynman, continually argued. Its conclusions, by definition, are provisional models which are subject to future revision as new data and better explanations arrive. The story of science is a chronicle of old models being superseded and new theories seeking to make sense of our world.

The claims of certainty about future consequences of global warming deserve particular scrutiny

Throughout its history, science has been misunderstood, sometimes deliberately, often to serve political purposes. Genetics and evolutionary biology are areas where a specific and partial understanding of scientific findings has repeatedly been annexed by ideology. Climate change is another.

The best available evidence we have strongly indicates that man’s economic activity contributes to the warming of the planet. That is undoubtedly the prevailing scientific consensus. But it is not unscientific to question how conclusions have been drawn from that theory to dictate human action. It is not, as Ed Miliband, the Energy Secretary, would have it, ‘denial’. It is the scientific method at work.

A properly scientific approach to global warming must consider not just the impact of man’s activities, including carbon emissions from fossil fuels, but other factors that bear on the hugely complex system which is the Earth’s climate. The theoretical work behind the warming effect of emissions is robust, yet the claims of certainty about future consequences deserve particular scrutiny.

Campaigners and politicians have predicted terrifying consequences with a level of pessimism that sounds more like the utterings of a millenarian cult than the scientifically literate offering a judgment on likely probabilities. Those same people have weaponised the precautionary principle, taking what is a possible future risk and elevating it to a certain apocalypse that justifies the most drastic action. Nations have been asked to arrest economic development, desist from the use of efficient sources of energy, distort market signals and throw the pace of growth into reverse in order to slow global warming.

A series of international conferences – the latest of which is COP30, taking place in Brazil this week – require participants to commit to energy policies that depend on state direction, legal compulsion, taxpayer subsidy and thermodynamic legerdemain. Britain’s Labour government is leading the crusade, which is why we have the highest energy prices in the developed world. Other countries affirm the importance of these policies but take, at best, a more Augustinian approach: make me net zero but not yet. Brazil is driving ahead with the exploitation of its fossil fuel resources – planning to invest $100 billion in oil and gas production over the next five years, increasing production by 20 per cent – and China is manufacturing solar panels for us while building new coal power stations for itself.

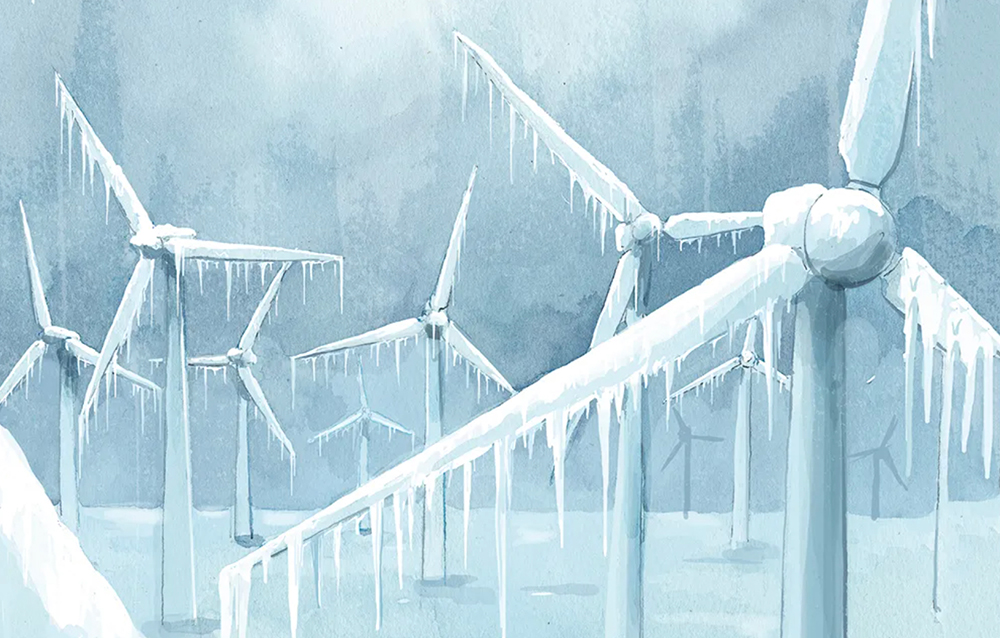

It is not in any way immoral or illegitimate, let alone unscientific, to ask if the commitments we are making are justified. That is precisely the question Bill Gates is now asking. Britain is set on a course that requires us to leave efficient energy sources in the ground, which countries like Norway are happy to exploit. We rely on our neighbours for our energy supplies. We subsidise wind and solar power which, because of their intermittency, still require us to have fossil fuel infrastructure as a back-up. We are giving up productive farmland and risking environmental damage to install yet more renewable energy infrastructure. And we are accepting de-industrialisation and the weakening of our sovereign defence capacity along the way. As the former MI6 chief Sir Richard Dearlove explains, we are giving the Chinese Communist party effective control over more and more of our economy, further compromising our national security in the process.

These costs are certain. They are rising too, unlike the sea levels that climate alarmists predicted would have submerged several island nations by now. It is still true that future climate change is likely to bring significant challenges for poorer societies – but we are unlikely to be in a position to help those nations adapt if we ourselves are weaker and poorer.

It is because debate is needed on energy and climate policy – all the more so because of the vehemence with which some try to shut it down – that The Spectator is committed to publishing a series of articles in the coming weeks that will examine the costs of our current approach and the assumptions underlying it. The first essays in this series are Sir Richard’s analysis of the security risks of energy policy and Matt Ridley’s exploration of the possible benefits from investment in fusion research. We welcome as wide a range of views as possible in reviewing these questions. Science is not served by the hunting down of heretics but by the opening up of inquiry.

Comments