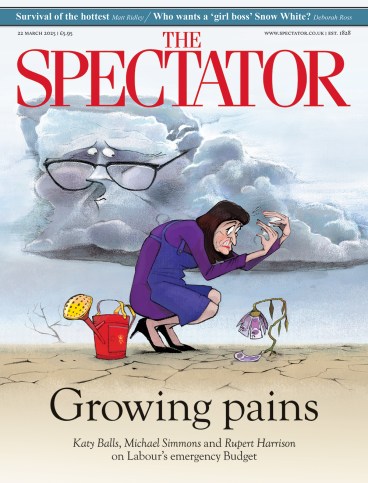

Next Wednesday Rachel Reeves will stand up in the House of Commons to deliver what she is calling her ‘spring forecast’. As so often with political language, everyone in Westminster knows it is no such thing, just as there was nothing ‘mini’ about Kwasi Kwarteng’s Budget of September 2022. The ‘spring forecast’ will be an emergency Budget, and the reasons for it reveal a surprising truth about the Chancellor of the Exchequer: she is an inveterate gambler.

Unless everything turns out to be a brilliant exercise in expectation management, the worst-kept secret in Whitehall is that Reeves has already broken her ‘iron-clad’ fiscal rules. The Chancellor’s team will receive the Office for Budget Responsibility’s final forecasts, but the damage has already been done by negligible growth, rising interest rates and higher than expected borrowing. As a result, there has been a rushed attempt in the Treasury to cobble together savings from the welfare budget and cuts to departmental spending to make the sums add up.

For the Chancellor to be forced to come back and change spending plans within six months of a ‘once in a parliament’ Budget – and in the middle of a spending review – is unprecedented and, frankly, embarrassing. The Treasury spin operation has tried to disguise this embarrassment by claiming that the world has changed: defence is the new priority, and welfare savings were always planned. But nobody is falling for it.

The truth is that, just as with her first troubled Budget in October, Reeves’s own rash decisions have come back to bite her. In that Budget she increased taxes by £40 billion a year and added £30 billion to annual borrowing, yet left only £10 billion in headroom. Almost every commentator at the time pointed out this was cutting it very fine. The whole point of building up fiscal headroom is that the world does change all the time. Reeves bet the house on her cards turning up trumps and instead she got Trump.

This has real consequences. The ballooning cost of sickness and disability benefits is one of the most pressing issues the country faces, but the current policy approach is driven by the need for short-term savings, not a coherent strategy for rewiring the faulty parts of the system – most notably, the way the definitions in the Work Capability Assessment and Personal Independence Payment are administered. The crisis in public sector productivity is a social, fiscal and economic disaster – and deep public sector reform should be the main focus of the spending review. But the Treasury’s approach has created a front-loaded spending profile with huge increases in the first two years of the parliament, followed by austerity-lite in later years. The plan is not believed by anyone in Whitehall or the markets. Everyone knows that unless she gets very lucky, the Chancellor will need to come back for more money at some point. Götterdämmerung may come as soon as the autumn in the (official) Budget, or it could come later, but it will come. The Chancellor likes to be compared with early period Gordon Brown, but instead of ‘prudence with a purpose’ her style is more like recklessness with her fingers crossed.

So what should she do? As it says in the ads, when the fun stops, stop. Reeves needs to stop gambling and get ahead of the curve by re-establishing meaningful headroom against her fiscal rules. Given the inevitable demands of her party for more spending on public services in later years, she should build this spending into her plans now.

The pressure from her party will be to achieve this by borrowing even more. Some Labour figures point to the way Germany is planning to increase borrowing to confront its under-investment in defence and infrastructure. This is dangerous talk. Britain’s debt is 100 per cent of GDP compared with Germany’s 60 per cent. We are living on the edge of sensible fiscal limits. The gilt market wobbles earlier this year are a warning.

What should happen is a deep and radical overhaul of the welfare system and a fundamental reform of the public sector to deliver higher productivity. In the absence of that radicalism, Labour faces a stark political reality: the spending it wants will need to be funded by higher taxes, including the big taxes the party promised not to raise.

The government has recently shown some signs of serious intent and intelligent decision-making: higher defence spending funded from the aid budget; abolishing NHS England; building new runways. The economic and fiscal strategy should be next. It’s possible that task will require a new chancellor, but for now Reeves has staked her chips on black and will be nervously watching the wheel spin.

Comments