At least James Cleverly had somebody to meet. The Foreign Secretary’s last effort to get to Beijing was postponed after his Chinese counterpart disappeared in late June. Former foreign minister Qin Gang has not been seen or heard of since. Gang’s whereabouts are as mysterious as Cleverly’s China policy, which is beginning to feel a lot like a re-tread of the incoherent and failed past strategy of ‘engagement’.

That policy, as far as it can be described as one, was driven by greed and gullibility. It added up to little more than kowtowing to Beijing, largely ignoring its growing repression at home and aggression overseas, while at the same time allowing Communist party-linked entities unfettered access to the most sensitive corners of the British economy and academia.

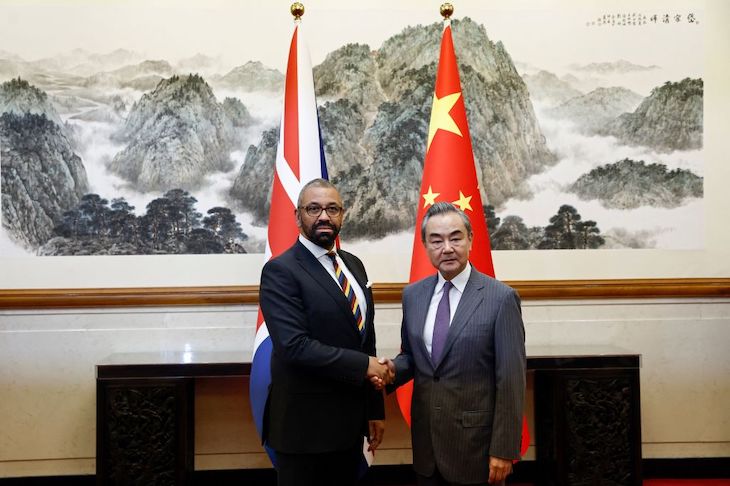

Cleverly, the first senior minister to visit Beijing in five years, met China’s new foreign minister Wang Yi (actually an old foreign minister re-instated) and its vice-president Han Zheng in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People. He said he’d raised human rights issues, ‘But I think it’s important to also recognise that we have to have a pragmatic, sensible working relationship with China because of the issues that affect us all around the globe.’

The problem is that China doesn’t see it that way

Cleverly has given few clues as to what a ‘pragmatic, sensible working relationship’ actually adds up to. And it was hardly encouraging when, ahead of his visit, the Foreign Office reportedly told government officials not to use the term ‘hostile state’ in case it upsets China, and to erase it from publications. Cleverly says he wants to be constructive. He cited the need to cooperate on climate change, investment and trade, as long as the latter did not create national security concerns. ‘The UK is open for business,’ he declared on the eve of his visit.

Yet there is little sign of Chinese interest in cooperation on climate change. It continues to build coal-fired power stations at breakneck pace, making a mockery of earlier, vague carbon reduction targets, and holds even limited cooperation hostage to Western concessions over high-tech trade and criticism of human rights abuses.

Cleverly believes he can separate issues like human rights and security, where he insists Britain can be robust, from desirable economic engagement. The problem is that China doesn’t see it that way, and routinely uses trade, investment and market access as tools for economic coercion. The UK is struggling to extricate China from advanced 5G telecoms networks and the nuclear industry, with deadlines missed on both. It should be remembered that all Chinese companies, whether nominally private or not, are required by law to help China’s security services on demand, and the ‘civil-military fusion’, the handing over of tech developed in the civil sector to the military is also required under Chinese law. The UK’s security services have warned about the continuing breathtaking scope of China’s espionage and influence operations in the UK.

China is becoming an increasingly hostile place to do business. The CCP has targeted foreign market research and due diligence companies – companies that provide crucial information services for foreign firms. A new cyber security law gives potential access to those firms’ systems and networks. A new espionage law bans the transfer by firms of any information related to national security, which is such a blanket term in China it can mean almost anything. Many firms now regard China as uninvestable, and their most pressing China challenge is to diversify their supply chains away from China, though you would never have thought that by listening to Cleverly.

It is true that Britain has acquired some potentially potent tools for countering China, including in a national security and investment law, under which foreign investment will be more tightly scrutinised. But such tools are largely untested and subject to considerable ministerial discretion. In other words, while these measures are welcome, the government has to have the will to deploy them.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak says he’s open to meeting president Xi Jinping at a G20 summit in Delhi next week. Sunak has also floated the idea of inviting China to his much touted Artificial Intelligence safety summit at Bletchley Park in early November. One can only imagine Britain’s top secret codebreakers turning in their graves at the thought of the Chinese Communist party sharing the stage. The CCP’s priority for AI is its own safety. Much like the internet, it wants to turn it into a tool and a weapon for security and control. President Xi sees no place for anything with a mind of its own.

The human rights picture in China is bleaker than ever. President Xi was in Xinjiang ahead of Cleverly’s visit, promoting the repressive policies that at one point imprisoned 1.5 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities. In Hong Kong, the police are harassing the families of exiles, including those in Britain, as the CCP continues to transform the former British colony into a grim and repressive police state.

Any hope that Cleverly might have that Xi will pressure his ‘good friend’ Vladimir Putin over Ukraine are misplaced. Beijing continues to effectively bankroll Russia’s aggression through its stepped up trade with Moscow and persists in echoing Moscow’s propaganda. It will also be looking for signs of Western weakness and any erosion of unity in support of Ukraine, as it plans how best to snatch Taiwan.

China has continued to harass the island with military exercises, a tactic that is likely to be stepped up ahead of presidential elections on the island in January – a democratic festival that would never be allowed in the increasingly grim totalitarian dystopia that is Xi’s China. Any China strategy should learn from the Ukraine war, and the dangerous energy reliance on Russia that it exposed. It should take a long hard look at the dangerous and even greater dependencies that Britain has on Beijing, and on how best to reduce that risk. James Cleverly’s vague China policy appears to be dangerously and painfully retro.

Comments