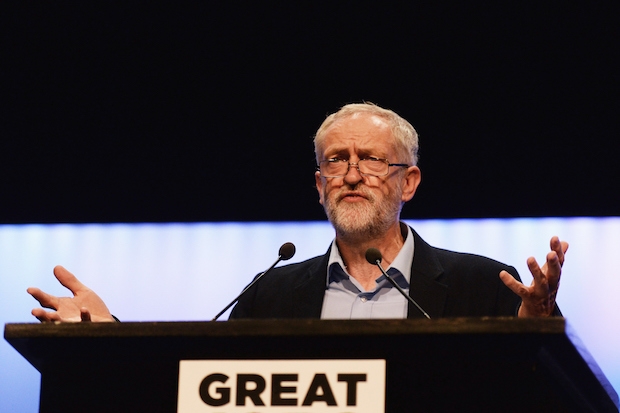

Perhaps the most teachable moment in the BBC’s coverage of Jeremy Corbyn’s speech to the TUC came around the 38 second mark in the video here. Corbyn is reaching an emotional climax. He’s already delivered his big line:

‘They call us [smacks lips] deficit deniers… but then they spend billions cutting taxes for the richest families, most profitable businesses, why, er, what they – what they are is poverty deniers… [hurries on embarrassedly in case ringing phrase results in disconcerting applause]… They’re ignoring the growing queues at food banks, they’re ignoring the housing crisis, they’re cutting tax credits when child poverty rose by half a million, um, under the last government to over four million…’

Most of the audience now realises, around the word ‘queues’, that the big soundbite was five or six words back and that it’s too late for a standing ovation. So on Corbyn soldiers with that awkward tricolon (‘ignoring…ignoring… cutting’) – into the backside of which he has intruded a mundane statistic, trailing two modifiers, in order to make absolutely sure he’s killed any hope of oratorical lift. Political rhetoric should leap and pirouette: that sentence is an overweight ballerina with a limp in one leg and an emu wedged in her bum.

‘Let’s be clear,’ he says, perhaps to show that in at least one respect he’s the heir to Ed Miliband, ‘austerity is actually a political choice that this government has taken, and they’re imposing it on the most vulnerable and poorest in our society… [hurries on embarrassedly in case ringing phrase results in disconcerting applause] It’s our job, as Labour…’

This time, though, his audience is on the qui vive. Not wishing to let another zinger slide by, they lumber into applause. And then the BBC cuts away to this dude, who as he claps perfunctorily away bears on his face an expression of infinite sadness such as I have seldom ever seen. It is the expression of an unfulfilled wife counting the cracks on the ceiling as she performs her conjugal duty and, too numb to cry, wonders where her life went wrong. I’ve never before seen an audience member at a political speech and actually wanted to give them a cuddle.

This is not the effect, my chickadees, that any speaker should be aiming for. I do not pass comment on Mr Corbyn’s policies, here. I’m interested in something much more important than that to him as a politician: his ability to sell them. This is the province of rhetoric. And at this, my oh my, he sucks…

So here are five things Jeremy Corbyn needs to get his oratory in some sort of order.

1. Own the material. This is his number one failing at the TUC. He’s reading falteringly off a bit of paper as if he’s sight-reading a speech written by someone else. That kills spontaneity and it kills the connection with the audience – ‘DOWN WITH TORIES… um, it says here’ isn’t the subliminal message a conviction politician wants to put across. You don’t have to memorise a speech: you do have to make it look like you’re delivering it not reading it, though.

2. Write the material. A speech needs a shape. It needs memorable phrases. It needs rhythm and spring. Deciding, as in the example above, whether you’re shooting for anaphora (repeating the same word or phrase) or tricolon (a group of three) and trying it out aloud might help. Aim for crescendo rather than diminuendo. Put your statistics in the talky bits and your feeling in the rhetorical bits. Parallelisms, echoes, antitheses, groups of three: these are not cheap tricks to be disdained, but ways of making material go over.

3. Pause. Not like you’re wondering where you’ve left your reading glasses, but like you want to let a point sink in. People – particularly if you’re a left-wing Labour leader addressing the TUC — will applaud: they really want to. And it’ll make everything else easier.

4. Make eye contact. This will come much more easily with #1. You can’t make eye contact if your eyes are glued to a script.

5. Think about ethos. This is the fundamental connection a speaker makes with his or her audience. They want to feel that you’re one of them, that you share their emotion, that you’re on the same team. This can encompass all sorts of gestures – doing your shirt button up at a memorial service, for instance, if you want to include floating voters in your ethos appeal – but at its very base is giving the audience the sense that you are making an effort to reach out to them. Sounding engaged, passionate and personal isn’t a shameful trick of the Westminster elite: it’s the basic bar for entry if, like Mr Corbyn, you are now whether you like it or not in the full-time business of public persuasion.

Sam Leith is The Spectator’s literary editor and author of You Talkin’ To Me?: Rhetoric from Aristotle to Obama

Comments