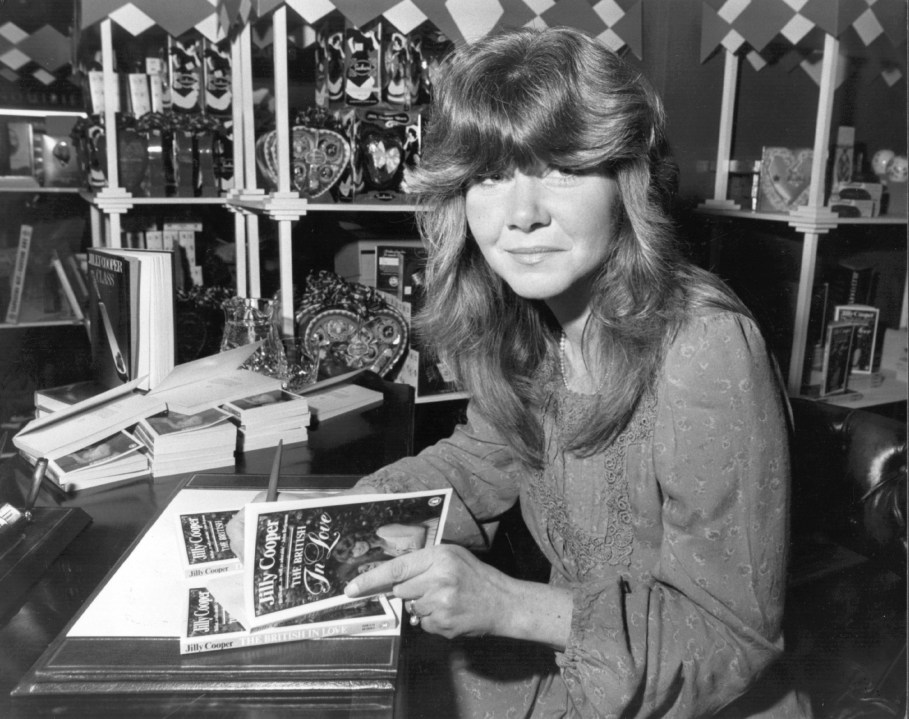

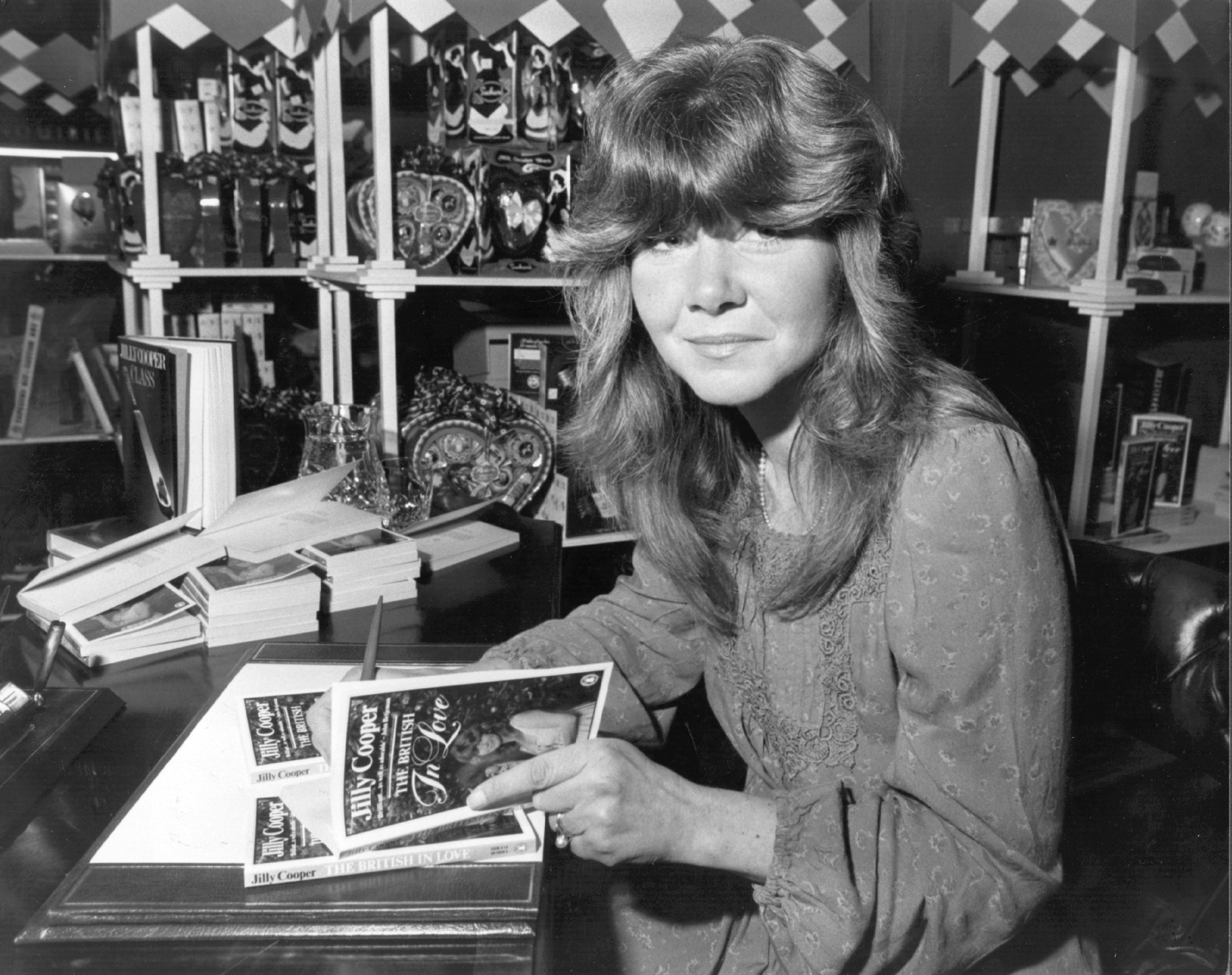

Dame Jilly Cooper, who died today, finally achieved the acceptance that she’d always deserved. She wrote numerous volumes of witty, clear-sighted journalism, London-based romances like Prudence, Bella and Octavia – and, of course, her ‘Rutshire Chronicles’ series, set in the Cotswolds and featuring the wicked homme-fatale and aristo-sexbomb Rupert Campbell Black. They were books hoovered up as much by adults as by teenage girls and – though they hid the fact – often their younger brothers.

There remained a widespread snobbery about her ‘bonkbuster’ novels – largely, perhaps, because they dealt mainly with the middle and upper classes

Yet there remained a widespread snobbery about her ‘bonkbuster’ novels – largely, perhaps, because they dealt mainly with the middle and upper classes. Following the recent success of Disney Channel’s Rivals (adapted from her 1988 novel), producer Dominic Treadwell-Collins spoke of the failures he’d had over the years getting anything by her onto the screen, and the disdain for her work he found amongst TV executives: ‘Throughout my career I had kept mentioning Jilly and everyone sort of laughed at and ridiculed me.’ With the series’ hugely positive reception last year and the high ratings it received (Rivals was in the US top ten of most-streamed series for three weeks), Cooper, it seems, had the last laugh at all of them.

Those of us who grew up reading her novels – finding them a perfect bridge between childhood reading and Literature with a big ‘L’ – knew that any down-to-earth television producer was sitting on a goldmine. We were formed by these books, reading and rereading them, often thinking the things we did in adulthood, and wanting some of the things we wanted, because of words she had written. Nobody knew better how to sell the romance of a cosy King’s Road wine bar, a drunken country house party, a Cote d’Azur seafront or simply a warm summer’s evening on Wimbledon Common.

She created thoughtful, funny, slightly neurotic heroines (most of whom, you suspected strongly, were versions of herself) and marvellous damn-your-eyes heroes – Cory Erskine, an alcoholic novelist in Harriet; Ace Mulholland, ‘beetle-browed’ foreign correspondent in Prudence; Emily’sRory Balniel, a tormented and Byronic Scottish artist with a secret; and of course Rupert Campbell-Black, the show-jumper turned MP who made generations of schoolgirls swoon. If any found the books laughable, you imagine Cooper, sometimes nicknamed ‘Silly Jilly,’ wouldn’t have minded much, nor taken herself seriously enough to be offended. Fun and laughter – and above all, groanworthy puns – were her stock-in-trade. ‘I cannot pretend these stories are literate,’ she wrote in the introduction to Lisa & Co.,a collection of her short stories. ‘They are written purely to entertain… their mood is rooted firmly in the sixties, when we all lived it up and had a great deal more fun, I think, than people have today.’

Here she was selling herself short. Entertain, she certainly did – her characters were always likeable and even the nasty ones were always enjoyably awful, Her evocations of London in books like Prudence and Octavia also made you love the city more, while showjumping competitions and TV franchise battles in her breezeblock-sized Riders and Rivals were brilliantly recounted and often nail-bitingly tense. Cooper was light, talented and hugely popular, and for this too her critics couldn’t forgive her. Yet her annoying tendency to stay in print and grab legions of new fans as the decades went by told another story.

Besides, the snobbery was misplaced. It was clear Cooper had read and loved the classics – you see in her books the influence at times of the Brontes, Jane Austen, even Shakespeare (the heroines in her comedies, usually based in Chelsea or Kensington, are invariably transported to a magic forest – be it a crumbling pile in the Lake District, a narrowboat or a Scottish Island – where partners are swapped, wrongs are righted and our woman emerges at the end with the Real Deal Alpha Male). Amidst all the drinking, smoking and bedhopping, Cooper would namecheck Yeats’s poems or Chekhov’s The Seagull, but it was always done lightly, and in a way that made culture seem fun (that word again) and worth pursuing. Pseudo-intellectuals and professional academics – along with power-hungry lefties and humbugging members of the clergy – always got short shrift from her.

Some of us left behind owe her a huge debt. She made you excited, as a teenager, about growing up, and that was help enough. She also taught us what a comfort reading could be, and that an intelligent, witty and sophisticated adult could invite you into their world, warmly and unpretentiously, instead of leaving you, as so many writers did, floundering about in the cold.

If some of us grew out of her books, that was also true of Roald Dahl’s and Edith Nesbitt’s – and just as much a fact that in time we’d grow back into them, and marvel that such brio, expertise (and hard work) could be made to seem so effortless. As for her legacy, the best Dame Jilly could bequeath to us would be that the fun should continue and the party go on.

Comments