‘Coad. Coad.’ I wracked my brain. Distant bells began to tinkle as I turned the name over. As though performing a solo game of charades, I said to myself ‘Sounds like?’ And I landed on it.

Jonathan Coad used to be known only to a small band of aficionados. Happily today he is almost a household name. This is because of his participation in what must be regarded, by some stretch, as the most catastrophic interview ever conducted on British television. And I have not forgotten about Michael Howard, Prince Andrew or Cathy Newman.

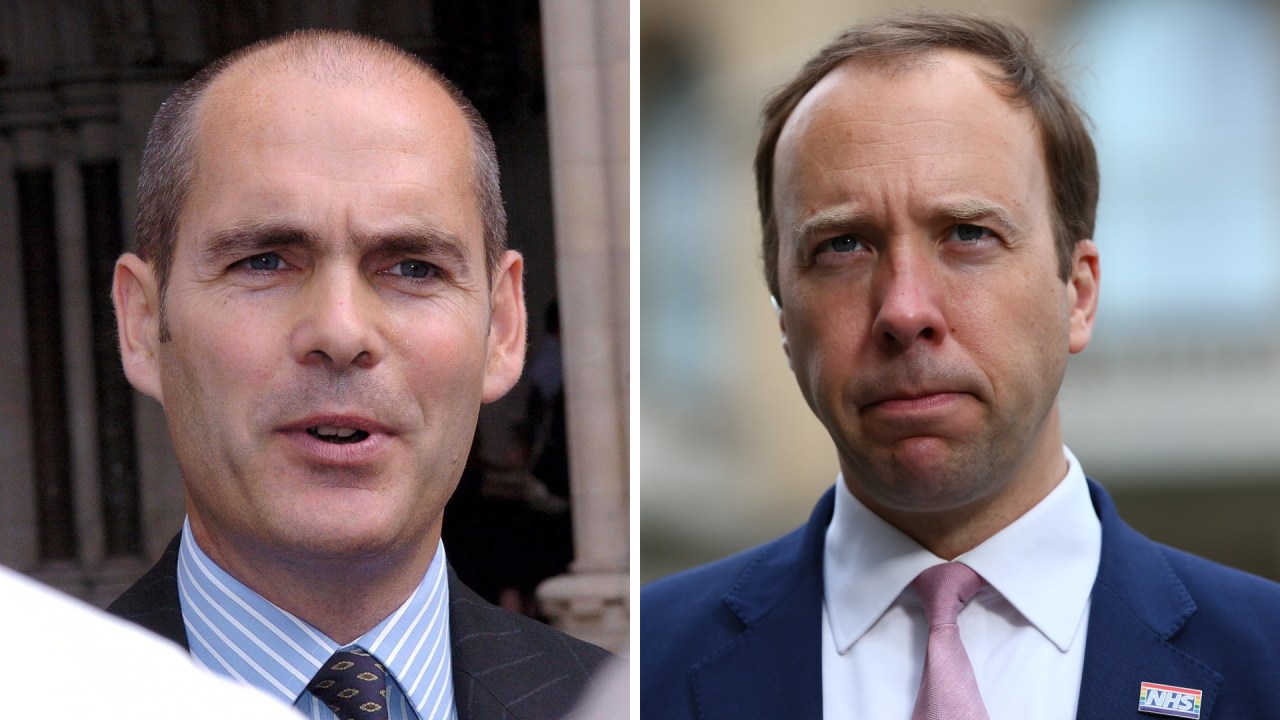

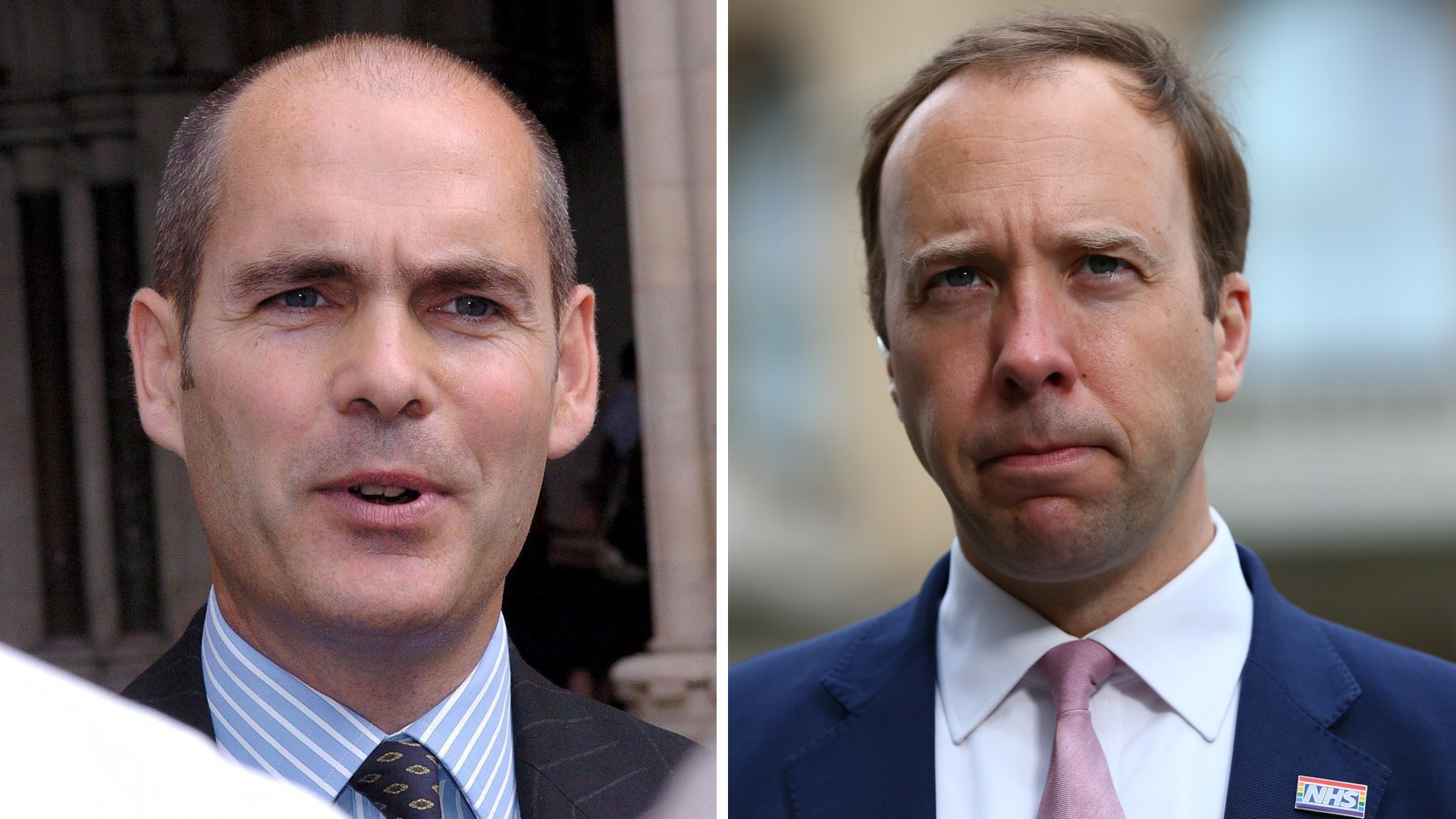

This week Mr Coad was on GB News being questioned about Matt Hancock, WhatsApp, Isabel Oakeshott and the various other intrigues preoccupying us as our nation goes down the swannee. Right at the start, Coad was introduced as a lawyer who ‘was recently asked to act for Matt Hancock’. Mr Coad – who rocked back and forth throughout the interview – opened menacingly by saying that this introduction was ‘disappointing’. With a mildly threatening pomposity, he said: ‘I made it absolutely clear to your programme. I asked them not to disclose that. And that is very, very poor journalism.’ He went on to explain that in correspondence with GB News producers, he had mentioned that while he was happy to come on to discuss the situation with Matt Hancock, he did not want the channel to say that he had been approached to act for Mr Hancock.

Coad is one of those lawyers who seems to have developed some sort of circular breathing technique

The GB News presenter was as polite as he could be about all this, apologised about any misunderstanding and tried to carry on. Unfortunately, Coad is one of those lawyers who seems to have developed some sort of circular breathing technique. He can talk for hours without ceasing. On live television this is not always a virtue; occasionally the interviewer might like to get a question in. But Coad is one of those people who, if they are talking and somebody says ‘May I?’, will suddenly say ‘Stop interrupting me’ and look furious until their effluent flow is allowed to resume.

On this occasion the torrent only finally stopped when the presenter, Steve N. Allen, pulled up the email that Coad had sent to his producers. While agreeing to talk about the case of Matt Hancock, Coad had written: ‘I would be grateful if it was mentioned that he [Matt Hancock] asked me to act for him.’ This would strike me as entirely in line with the character of Mr Coad. ‘I am an expert and would appreciate it if you told your viewers just what an expert I am’ would seem to be the gist of his guidance to producers.

Only at this point did Coad himself realise his boo-boo. As cruel cackles broke out off-mic, Mr Coad was forced to say: ‘It’s my mistake, I missed out the “not”. I take all of that back. You’re right and I’m wrong.’

It was gracious of him to admit it. Coad is not the first person to make this mistake. Older readers may remember the case of the so-called ‘Wicked Bible’, published during the reign of Charles I, in which one of the compositors fatefully left out a ‘not’ from the Ten Commandments. On this occasion the error led to one of the injunctions reading ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’. Nobody knows how much sinning was done on the sly by 1630s readers enjoined to act on this commandment, but the printers certainly got into all sorts of trouble. My point is that Mr Coad is not the first person to waylay a ‘not’. Though he is perhaps the most enjoyable.

But why do I linger on the public embarrassment of this Coad? And why – you may equally ask – did bells tinkle in the memory at the mention of his name?

Only because here at The Spectator we too have been on the receiving end of the Coad-meister. A couple of years ago I wrote in this space about the then vice-chancellor of Cambridge University, a second-rate dolt from Canada who tried to make Cambridge unrecognisable until certain adults intervened. Stephen Toope has since stepped down early from his role.

In any case, at the height of l’áffaire Toope, we received a most interesting piece of correspondence in relation to the noble vice-chancellor. Some readers may remember that as well as ordering historical inquiries into whether Cambridge University had in any way benefited financially from the past, Toope attempted to impose a set of guidelines to faculty and students relating to micro-aggressions and the like. One example of a micro-aggression was anyone raising an eyebrow whenever any member of a minority group spoke. As I mentioned then, a Cambridge with ne’er an eyebrow arched is not a Cambridge that I, for one, would recognise.

Toope and I got into a sort of running battle on the matter. He insisted that the guidance had not been published per se, or at any rate had been published but then also unpublished. At some point I think he complained the dog had eaten the guidance. Anyway, at this point Toope sent for the big guns. Yes – as fate would have it, he sent for the one and only Jonathan Coad, who got in touch with the sainted editor here and complained about the facts on behalf of Toope. This was not a wise move on the part of Toope, for he was in the middle of a crisis. A crisis he was intent on covering over and fixing. On this occasion The Spectator published Mr Coad’s words, while mentioning that Coad is ‘a PR professional and media lawyer who specialises in crisis PR experience protecting top brand and corporate reputations’.

If I have learned one lesson in this life, it is that if you are in the middle of a crisis and wish to deny that you are in the middle of a crisis, you should refrain from hiring anyone who rushes into every room and announces themselves as a crisis management professional. It can undermine the general thesis, as it did on that occasion.

Why do I mention all this? Doubtless some larger lesson could be found. In the meantime I simply rejoice in Coad’s talents gaining wider appreciation and reflect, not for the first time, on the simple childlike joy of gloating.

Comments