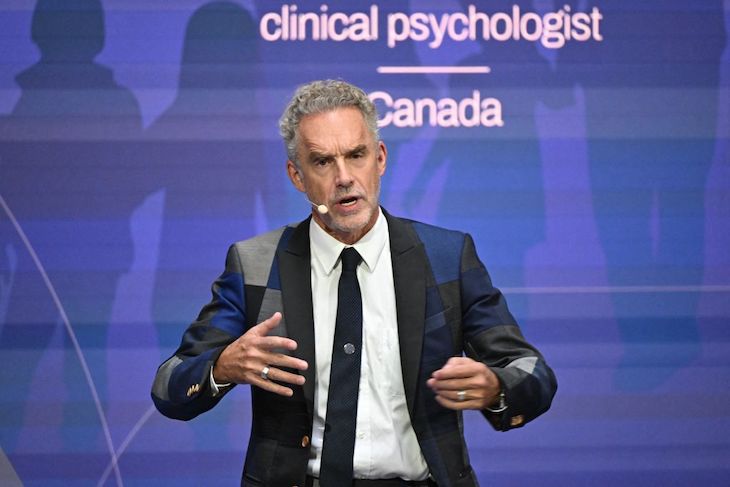

Jordan Peterson is a cross between a student who has lately discovered the meaning of life, and a professor who has known it all along.

In an interview in this week’s Spectator, the former persona is sandwiched between two slices of the latter. First he holds forth about the Bible in a ponderous way, in order to give us a taste of his new book. His thesis is that the supreme story is one of unity and order, not the chaotic play of secular power, and also that sacrifice is of fundamental importance.

These are substantial ideas, but they are presented with slow pomposity, as if only now are they fully understood. But they are hardly new: some of us were pondering them back in the 1990s, thanks to the radical orthodoxy theological movement and the work of the late French scholar René Girard.

The second slice of know-it-all professor is the predictable culture-war stuff. Peterson tries to outdo his fellow pundits by casting aspersions on his opponents, which will only impress a certain proportion of us.

Peterson keeps it ambiguous and vague

So what is his appeal, if he just offers some thirty-year old theology, and some culture-war vehemence? His unique selling point is his reluctance to declare his hand, on his religious position, and his semi-claim to be a prophet of some new revelation. This relies upon an ambiguity: is he is a Christian or not? If he clearly declared himself to be one, his aura would fade, because he would be positioned as just another official Christian. And he would have to plump for a particular denomination – a Christian-in-general is not taken seriously by other Christians. This would oblige him to defend certain things he might not be comfortable defending (the role of the pope, or the authority of scripture, say).

So Peterson keeps it ambiguous and vague. But the price of this is that he has to claim to have a major new insight into Christianity:

‘I’m not a typical Christian because I’m striving for understanding above all.’

The implication is that he puts himself in a risky and exposed position, for the good of the tradition – like a prophet. He then confirms this:

‘I’m a new kind of Christian. How about that? The manner in which I’m discussing these stories in my work has attracted a wide attention from precisely the people who were most disenchanted with the approach of the classic churches.’

In order to communicate the truth in a fresh way, he must keep his distance from conventional Christianity. That is his claim.

I have mixed feelings about this. Such posturing is a phase that many young people go through, as they discover what they think. I did. Also, I acknowledge that many interesting modern thinkers and artists have been on the edge of conventional religious allegiance in this sort of way. But Peterson is not, on present evidence, a major thinker or creative genius. The adulation of millions of middle-brows does not make you one. And so, in reality, he is an overgrown student type, doing in public what one is meant to do, decades earlier, in a secret journal.

A grown-up Christian thinker acknowledges his or her dependence on a tradition, which roughly means a denomination. It’s an admission that the big questions of faith have been tackled by many people before one, that one’s own attempts at understanding are part of a very long story. It also means that one is accountable: one has to face the sort of challenges that people naturally make about a particular religion’s relationship to politics and culture. One can’t float free of these basic difficult issues. Serious theologians see this as good and proper: it keeps one’s feet on the ground.

A few years ago I predicted that Peterson would become a Roman Catholic. It now seems that he is too wedded to his idea of himself as a prophet to join a particular church. I advise him to climb down from that self-image.

Comments