There is a famous piece of film — well, famous to those of us who know more about the Beatles than is possibly good for our health — where John Lennon encounters a fan who has broken into the star’s Berkshire estate. Clearly a lost soul, the fan is searching for meaning, signficance, some sort of connection with his idol. Lennon replies, very calmly and kindly: ‘I’m just a guy, man, who writes songs.’

Sadly, this book proves him right.

The good stuff first. It looks beautiful: the cover is ‘Imagine’-white, the pages carefully designed to weave Hunter Davies’s commentary around both the letters themselves and their transcripts. There are sweet moments, as when Lennon explains to a neighbour’s son that he and Yoko understand the boy not wanting them at his 12th birthday party: ‘We felt as bad as you! Please don’t worry about it — I might find an old amplifier for you.’ There are amusing moments, as when he sends Paul McCartney a copy of (what he thinks is) the famous audition tape rejected by Decca: ‘They were a good group; fancy turning THIS down!’ And there are moments of real emotion, as when he writes to his first wife from a 1965 American tour about missing their son Julian: ‘I spend hours in dressing rooms and things thinking about the times I’ve wasted not being with him.’

But overall the book fails, for the very simple reason that the content simply isn’t there. Davies has clearly struggled to find as many good letters as he would have liked. Context has sometimes departed, taking with it any interest the entry might have held. ‘John is thanking someone for a new kitten,’ Davies explains at one point. ‘George is also, presumably, the name of another cat, or it could of course be George Harrison.’ The book is padded with shopping lists, instructions to staff and so on. Such documents can often be more revealing than formal correspondence. Not here. A typical note reveals that Lennon wants a replacement table for the TV in his bedroom, and that it ‘must be at least the same height as the one now in use’.

Even the parts that held most promise deliver little. We learn nothing new about the difficult post-Fabs relationship with Macca; the rant in which Lennon tells him to ‘get off your gold disc and fly’ is already well known. A sequence of letters to Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ press officer, shows nothing more than that Lennon’s typing, dodgy enough to start with, responded badly to alcohol.

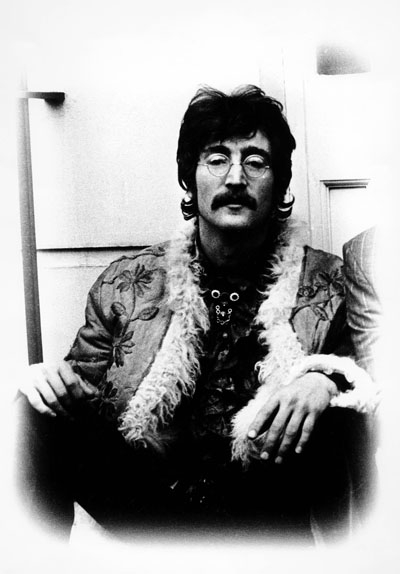

The book is not unworth its price tag, assuming you’re a Lennon fan who wants repeated examples of his signature (with the trademark ‘spectacles’ cartoon self-portrait underneath) and the occasional snippet you were previously unaware of, in my case that two of the backing singers on ‘Across the Universe’ were fans waiting outside the studio (McCartney emerged and asked if any of them could hold a high note). Most of the book’s value, though, lies not in the letters but in the meaning given to them either by hindsight (‘I bet I live till a ripe old age’) or Davies’s anecdotes about his friend. He told the twenty-something Beatles that he had just written their obituaries for the Times to keep on file. ‘Three of them shook their heads, tut-tutted, looked shocked, said how creepy. Only one of the four asked to see what I had written. And that was John.’

The perfect example is a postcard showing Lennon’s psychedelic Rolls-Royce. Davies gives us three interesting paragraphs on the vehicle’s history, including the fact that it had one of the first car phones in England. Then the postcard itself reads, in its entirety: ‘Dear Norman, Happy 79, Cheers, Love, John and family.’

The main message you take away from this book is that John Lennon was congenitally bored with life, constantly looking for new experiences, new modes of expression, new targets. This resulted in never-ending wordplay that gets tiresome (‘love and dressed fishes’, ‘touch woodworm’), activism that seems vacuous (‘Nutopia has no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people’), and attacks on critics that look petty (‘why don’t you give your job to a writer?’) It also resulted in some of the most brilliant music the world has ever heard. In the end he was just a guy, man, who wrote songs.

Comments