Angus Colwell has narrated this article for you to listen to.

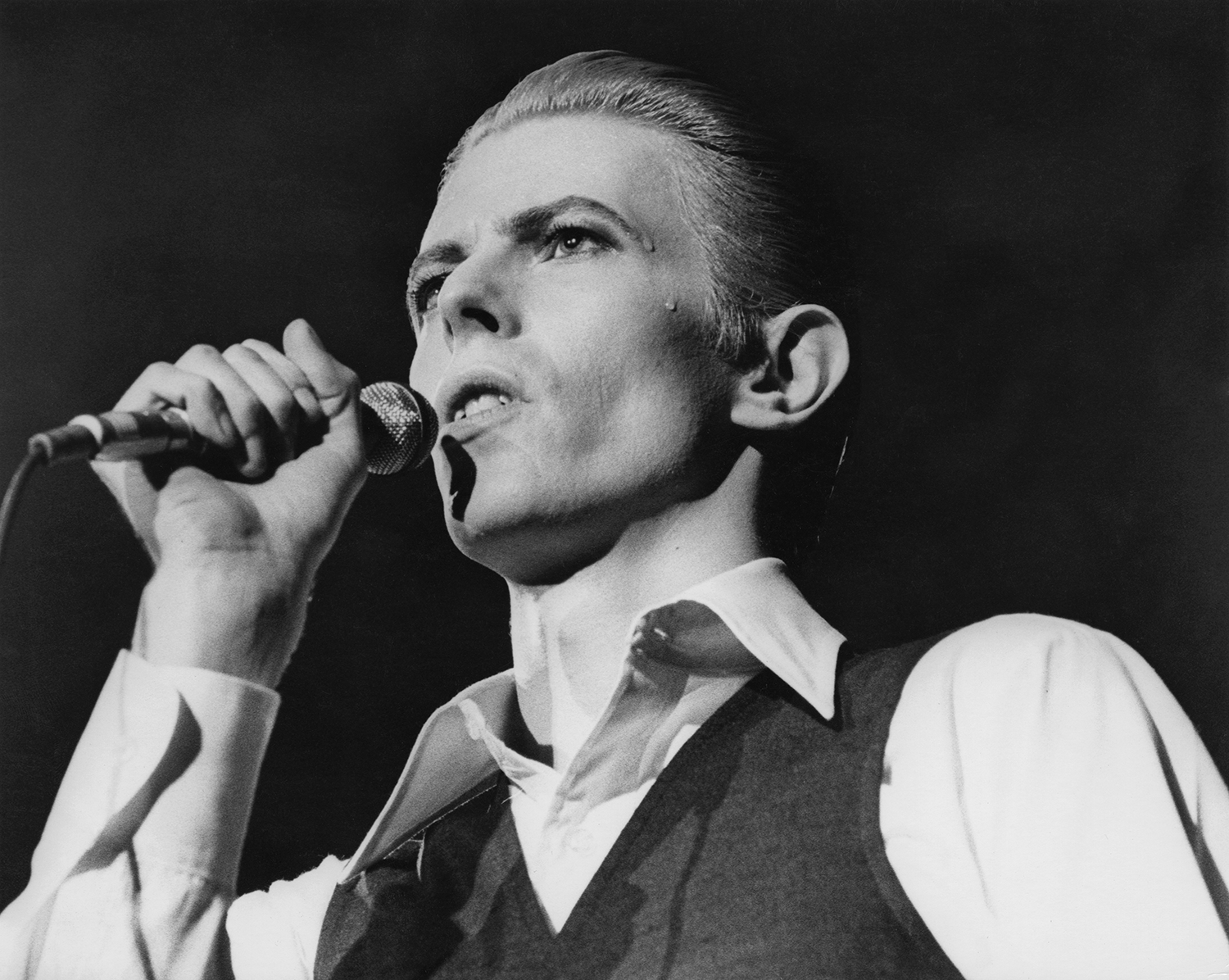

In January, it will be ten years since David Bowie died. I remember Bowie songs playing out of every London orifice that day. People who only knew ‘Life on Mars’ went down to the Brixton mural and cried. And then, for a whole year afterwards, the BBC’s arts coverage consisted entirely of salt-and-pepper fatties sitting in studios, in the mandatory uniform of T-shirt and blazer, all of them finding different ways to wheeze: ‘Day-vid Bow-ie chay-nged everyfing.’

As we approach the anniversary, the BBC is having another go – except this time with Kate Moss. ‘This is David Bowie Changeling’, Moss purrs, inaugurating a nine-parter on BBC Sounds and Radio 6 Music. Moss and Bowie were friends: he sent her to collect a Brit Award for him in 2014. She has a lovely voice to be fair, a voice that makes you think that smoking a million cigarettes a day for decades is a no-brainer.

Moss evidently hasn’t left her Cotswolds home to do this. The audio – very clearly some kind of Zoom recording – is poor. Regardless, the series has managed to get some good guests. They’ve got George Underwood, the guy who punched Bowie in the face when they were teenagers, thus discolouring one of his eyes. They’ve got Tony Visconti, his former producer.

Best, though, is that there’s plenty of Bowie himself talking, and he’s wonderful. ‘I think that throughout the Sixties and most of the Seventies, I was driven by lust,’ he drawls. ‘It’s a great creative force. That in turn is replaced by anger, when you ask where the money is. And then you get depression, and then you go to Berlin and write really moody instrumental stuff. It’s the triptych of the Seventies. Lust, anger, moody.’

The problem with this series, though, is that it’s too easy. I love David Bowie and I love nostalgia, so I should love David Bowie nostalgia. But not when it’s as hackneyed as this. The word so often used to describe him, ‘chameleon’, is heard in the first ten seconds. Seriously? You’ve had ten years to think of something else.

The programme also focuses on the years of Bowie’s career that it’s ‘safe’ to like – the years that, all too cutely, speak to the platitudes and preconceptions of identity politics. This is the early period. It details his rise out of the ‘suburban curse’ – as he called it – of Brixton (today that would be ‘central London’); the ‘Space Oddity’ single; the Ziggy Stardust persona. All of these bits are notable, yes, but they’re also ripe for ‘relevancy’. He cross-dressed! Let me say something banal about gender.

This leads to problems. By interviewing celebrities – like Vogue’s former editor Edward Enninful, or Robbie Williams, or Florence Welch – you get a strange read on Bowie. Most people just liked Bowie’s tunes. But if you listen to celebrities talk about him, it’s as if 1970s Britain was a world in which every kid was madly desperate to express their androgyny, where every kid was a repressed container of artistic genius. We also forget that Bowie was one among many idols – some of them quite different to Bowie. My dad’s first gig, for example, was a Gary Glitter concert, and he reminds me what an exciting cultural experience it was for teenagers.

Bowie himself is more honest about his various personas. His motives were cynical: ‘I was very vain.’ The third episode focuses on his ruthless desire to be famous, to be as big as Elvis. This was not an expression of identity, but a calculated quest for celebrity. The series stops just before this direction disintegrates, and just as Bowie becomes the Thin White Duke character. I was begging to hear the BBC describe his years as the Thin White Duke. This was when he produced some of his finest work, while living on a diet of cocaine, milk and red peppers, and proclaiming his love of Hitler. (Listen to ‘Subterraneans’ on the Low album, a song that sounds like being stuck on an amber traffic light for eternity.)

That era is an example of the true weirdness of Bowie, how his art didn’t furnish us with any easy moral lessons. He loved Julian Jaynes’s The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. He played Pontius Pilate in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. When he died, he was writing music for SpongeBob SquarePants.

This is the stuff that the BBC shies away from because it’s too hard to fit into a neat narrative. David Bowie did not leave us with a coherent and didactic body of work. Yet he did equip the media class with a formula for expressing how cool they are. Unfortunately, this series is no exception.

Comments