In 1929 the founder of Italian Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, reported from Milan that, after a wartime setback, the movement was ‘in full working order’ under the leadership of ‘the very young and very ingenious Bruno Munari’.

Bruno Munari (1907–1998) was 22 at the time. He had arrived in Milan two years earlier as a refugee from his family hotel business in the Veneto and embraced with enthusiasm Giacomo Balla’s suggestion in The Futurist Universe that ‘useful and pleasing’ consumer products in shop windows were ‘a much more rewarding sight than the grimy little pictures nailed on the walls of the passéist painter’s studio’. Although he was only active in the movement for three years — a period he later dismissed as ‘my Futurist past’ — he kept the faith. When other Futurists slunk back to passéist painting, the ingenious Munari kept his focus fixed on Futurism’s original dilemma: how to express the dynamism of the machine age in art.

Bruno Munari: My Futurist Past is the Estorick Collection’s charming, if belated, introduction of this little-known artist to British audiences. For despite a string of avant-garde claims to fame — as a pioneer of kinetic art, installation and video projection — Munari remains a rather well-kept secret, largely thanks to a taste for throw-away materials that led to much of his best work being thrown away. In those far-off days, commercial galleries hadn’t yet mastered the art of selling low-cost goods at high prices, and Munari’s Blue Peter aesthetic failed to find a market. While his paintings were preserved, his surviving sculptures are mostly ‘ones he made later’ in limited editions. On the plus side, his inability to make a living from fine art channelled his creative talents in commercial directions, making him the prototype of the modern multidisciplinary artist.

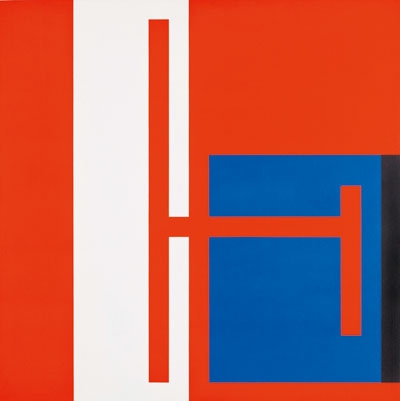

‘What would Leonardo be doing today,’ he wondered aloud in 1952, ‘the Montecatini pavilion or an oil on canvas portrait of Miss Europe?’ What Munari was doing straddles two galleries. In Gallery 2 we see examples of his graphic work — witty photo-collages, advertising posters and those 1930s Aero-Futurist images of flight that unfortunately still smack of fascism. In Gallery 1 we follow his journey as a fine artist from a straight-down-the-speed-line Futurist drawing of a ‘Motorcyclist’ (1927) through an ‘ABC Dadà’ (1944) — incorporating collaged buttons, watch cogs, nibs and cocktail umbrellas — to a selection of abstract paintings echoing developments in Russian Futurism, De Stijl and the Bauhaus. Munari was precociously fluent in the visual languages of the international avant-garde: an illustration of 1927 shows the 20-year-old artist applying Russian Cubo-Futurist principles to that most Italian of mini-installations, the Christmas crib.

Like all good Futurists, Munari was mad on machines, but without Marinetti’s aggressive technolatry. The modern artist, he thought, needed knowledge of machines not in order to exalt their power but ‘to distract them so as to make them work erratically’. He announced this subversive programme to the world with the unveiling in Milan in 1934 of the first eight of his so-called ‘Useless Machines’, of which one survivor appears in the show. But it was with his 1950s series of spring-driven ‘arrhythmic’ sculptures made of flyaway materials — scraps of aluminium sheeting, flags and feathers — that his contrarian concept sprang into life. Even when stationary, as now, ‘Arrhythmia (Red Flags)’ seems somehow animate with its flag-bearing antennae quivering in the gallery air-con. (Not all his designs for ‘Useless Machines’ were entirely useless. One example illustrated in a 1942 book is for ‘Tail agitators for lazy dogs’.)

His decision in 1930 ‘to free abstract forms from the stasis of paintings and suspend them in the air’ was revolutionary, anticipating Alexander Calder’s mobiles by three years — one example from 1947 looks like a disassembled Mondrian on strings. To their creator, these free-floating forms had a poetic rather than a mechanistic function, as ‘objects to look at the way one looks at a drifting cloud having spent seven hours inside a factory full of useful machines’. He imagined them animated by their environments like ‘the movement of grasses in a field, the shape-shifting of clouds, the rolling of a stone in a brook’. Analogies with nature don’t seem far-fetched in front of his seminal light installation ‘Concave-convex’ (1947), in which a dangling form of folded wire mesh throws moiré shadows on to the surrounding walls like waves lapping over rippled lines of sand.

Picasso called Munari ‘the Italian philosopher’, but his art, though not ‘passéist’, is not conceptual either. It is purely and simply aesthetic. The machines he defined as useless ‘because they don’t fabricate, they don’t eliminate manual labour, they don’t save time or money, they don’t produce anything that can be sold’ were mad-professorial investigations into the forces shaping reality as we see it. As with all visual artists, his aim was to make the invisible visible. ‘How could it be done differently?’ was the question he continually asked himself — and, as this show reveals, the answers he arrived at were refreshingly different.

Comments