Is Evgeny Kissin, born in Moscow in 1971, the most famous concert pianist in the world? Probably not, if you stretch the definition of ‘concert pianist’ to encompass the circus antics of Lang Lang, the 34-year-old Chinese virtuoso who — in the words of a lesser-known but outstandingly gifted colleague — ‘can play well but chooses not to’.

But you could certainly argue that Kissin has been the world’s most enigmatic great pianist since the death of Sviatoslav Richter in 1997 – though, unlike the promiscuously gay Richter, his overwhelming concern with privacy does not conceal any exotic secrets. He has recently married for the first time, but chooses not to publicise the fact. I don’t see why I should name his bride, since he hasn’t, but it was obvious when I met him last week that he’s very happy.

No one close to Kissin will have been surprised that details of his romantic life are entirely missing from his Memoirs and Reflections, just published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson. The book is a mere 190 pages long and that includes a ‘select discography’ from which key recordings have been omitted — for example, the Mozart D minor concerto K466 that Kissin directed from the keyboard with the Kremerata Baltica in 2010. It’s the most gloriously full-bodied performance — powerful, delicate, with legato arches that could hold up a Bruckner symphony. To anyone who thinks Kissin did his best work as a wunderkind, I’d say: listen to this.

On the other hand, no one can forget that he was a prodigy, and nor should they: at the age of 12, he produced a recording of the Chopin piano concertos that still rivals the finest in the catalogue. In his mid-twenties he gave the first ever solo piano recital at the Proms. Not one of the hundreds of juvenile virtuosos from the Far Eastern piano factories has come close to equalling his achievement.

Although there are many things missing from Memoirs and Reflections, it’s also revealing. Kissin is still only 45, looks younger, and yet recorded Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto with Herbert von Karajan. The maestro had decided that he wanted this warhorse to amble along. Kissin was told that he ‘must not race’, or Karajan would hold back even further. ‘The result was a vicious circle,’ writes Kissin — though in the end he concluded that ‘Karajan filled these tempi with all the forces of his genius’. Critics didn’t agree.

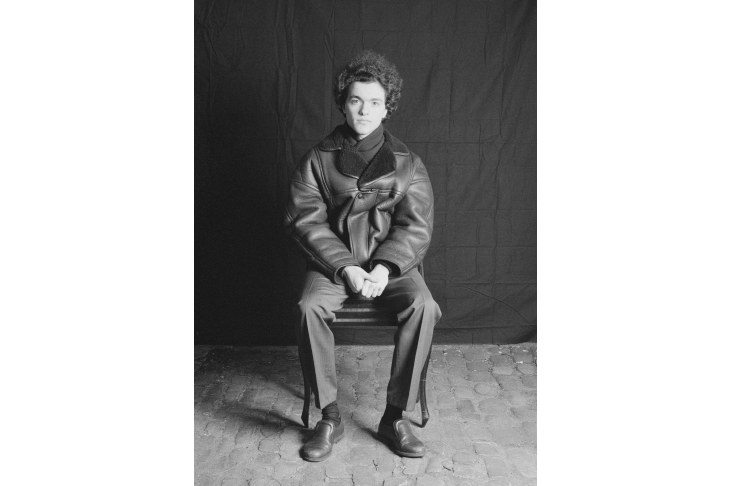

Stories like this suggest that the teenage Kissin was as comprehensively trapped as any pianistic prodigy in musical history. Philips made him one of the 100 ‘Great Pianists of the 20th Century’ before he turned 30. Society hostesses treated themselves to another facelift in the hope of seducing him. ‘He inspires adulation so irrational that it defies analysis’, wrote Stephen Wegler in International Piano magazine in 2004. Yet, he added, no pianist of his calibre received reviews that were ‘so personally nasty, even malicious … Because his curly hair tends to rise into a beehive. American critics seem particularly fond of comparisons with Elsa Lanchester’s grotesque appearance in Bride of Frankenstein.’ Kissin’s book hints that these were disorientating and suffocating years. Yet, it must be said, he can also dish it out. For example, he writes that he finds something ‘blasphemous’ in the way Josef Hofmann and Vladimir Horowitz approached certain works of Chopin.

Memoirs and Reflections is ‘compiled and edited’ by Marina Arshinova and translated by Arnold McMillin. So it’s a transcript of interviews, which is fair enough — but after talking to him for over an hour in the Spectator offices I’d say the last thing Evgeny Kissin needs is a translator.

His English is immaculate. You get the impression that a mixed-up tense annoys him as much as a dropped note in the whirlwind finale of Schumann’s Carnaval. Both things happen, but very rarely.

Kissin tends to pause for a long time before answering a question. I thought at first that he was tidying up his English in advance — but, actually, the extreme precision is necessary because he’s moving through a political minefield. No one asked him to enter it, but he feels he has no choice.

We’re not talking about musical politics here, but actual politics. And it’s a minefield because Kissin despises the soft-left consensus embraced by artistic aristocracy.

‘I am a staunch supporter of Western values,’ he says, ‘but in recent years I began to realise that unfortunately the Western establishment was often betraying those values. And one of the manifestations of such betrayal was its anti-Israel stance.’

In 2009, Kissin wrote to the BBC’s then director-general, Mark Thompson, accusing the corporation’s Persian service of perpetuating the ‘blood libel’ by reporting that Israel was harvesting the organs of dead Palestinians. What response did he get? ‘A letter trying to get out of it.’

Kissin describes himself as an Israeli-Russian-British citizen. The Israeli passport is the most recent — he took citizenship in 2013 — and apparently the one he values most.

He has celebrated his Jewish identity since his Russian childhood, ‘when amongst the people the word “Jew” was perceived as slightly indecent and better avoided’. As a young man he taught himself Yiddish and has recorded several CDs in which he recites Yiddish poetry.

His journey to becoming ‘a soldier for Israel’, however, was a long one — and inspired by the writings of a non-Jew, Vladimir Bukovsky. In 1994, the former Soviet dissident published a book called Judgment in Moscow. ‘For me it was a revelation, not because it exposed numerous communist crimes — these were no secret to me — but because it exposed how corrupt the Western establishment had been for many decades.’

Bukovsky’s book has never been published in English — ‘but I have it in my archive,’ says Kissin, and starts reading from his mobile phone. He chooses a passage in which Bukovsky says that ‘if you have the guts to keep killing people for long enough… then you are no longer a terrorist but a statesman and Nobel Peace Prize winner. This will not remain unnoticed by Hamas, nor the IRA…’

At which point, given that we were two days away from the general election, I couldn’t resist mentioning Jeremy Corbyn.

‘My late uncle, Lord Kissin, must be turning in his grave,’ he says. Harry Kissin, a prominent Labour supporter and refugee from the Nazis, helped secure permanent UK residency for the pianist and his family, plus his beloved teacher Anna Kantor, now in her 90s.

I wondered what Evgeny Kissin made of the European Union that Bukovsky detests.

‘I certainly don’t like what has become of it,’ he says. ‘Having grown up in the former Soviet Union I am for the independence of states. A common market is one thing but political centralisation is something completely different which I do not like.’ So he doesn’t blame Britain for voting to leave? ‘No. We’ll see what the results will be, but I certainly understand the majority of the British public who voted for it.’

To be fair to Kissin’s critics, many of them simply do not warm to his playing, whose emotional detachment troubles them. On the other hand, defending Brexit is the gravest heresy in classical musical circles. You have to wonder: will his pugnacious opinions influence the critical reception of the first fruits of his new exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, a double album of Beethoven sonatas? It’s impossible to say. But somehow I doubt that Evgeny Kissin could care less.

Damian Thompson talks to Evgeny Kissin on The Spectator Podcast.

Comments