The dust jacket of The Matter With Things quotes a large statement from an Oxford professor: ‘This is one of the most important books ever published. And, yes, I do mean ever.’ Can any contemporary work withstand such praise? The ‘intelligent general reader’ (the book’s target audience) should, however, not be discouraged, for Iain McGilchrist has to be taken seriously: a Fellow of All Souls, eminent in neurology, psychiatry and literary criticism, a thinker and — it’s impossible to avoid the term —a sage. His previous book, The Master and His Emissary, was admired by public figures from Rowan Williams to Philip Pullman. Some consider McGilchrist the most important non-fiction writer of our time.

Such enthusiasm is unusual for the narrow subject of our divided brains. But the neglected science of hemisphere difference, returned to centre stage by McGilchrist, provides the key to larger issues. Moreover, the earlier work, substantial as it is, seems to have been a preparation for The Matter With Things, whose two handsomely produced volumes contain the entire corpus of McGilchrist’s thought. Initially unreviewed, and undeniably long and expensive, its first print run nonetheless sold out quickly, and readers reported becoming completely immersed. It is now once more available.

Western civilisation is in a predicament exemplified by alienation, environmental despoliation, the atrophy of value, the sterility of contemporary art, the increasing prevalence of rectilinear, bureaucratised thinking and the triumph of procedure over substance. The lesser aim of The Matter With Things is to identify the common basis of those conditions, and to understand and perhaps improve them. But its greater purpose is to enable us to know the world we inhabit.

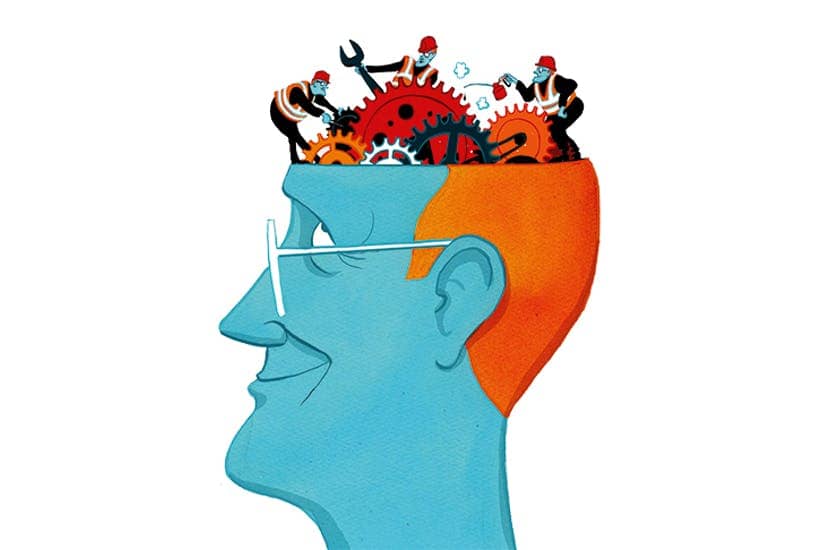

The world only exists for us inasmuch as we perceive it. We do so as embodied human beings, in particular through our minds. But clinical evidence shows that our divided brains offer two completely different ways of experiencing the world. The left hemisphere analyses lifeless parts; the right synthesises the living Gestalt whole. The right perceives the real landscape; the left constructs an artificial map. The right encounters the new, and is the hemisphere of music, poetry, humour and irony. The left is comfortable with categories, labels, the literal and the familiar. The two hemispheres constantly intercommunicate; however, since many aspects of language preferentially engage the left hemisphere, our modern, overwhelmingly verbalised existence promotes left-brain dominance. Yet countless studies demonstrate that in many areas the left hemisphere is obtuse, overconfident, fantastical and wrong. The right hemisphere, once misnamed the silent hemisphere, is better at understanding the world, whereas the left seeks to manipulate it. Self-validating left-brain modes of thought continually push us in the wrong direction, towards the hall of mirrors in which we now exist.

The ambition of The Matter With Things is to take the hemisphere hypothesis and to conduct through its lens a detailed examination of truth. McGilchrist discusses the paths that lead to truth: science, reason, intuition and imagination. A professional scientist, and thus a believer in the power of reason properly understood, he shows that both are easily corrupted by left-hemisphere thinking. The results of hyper-rationalism are often indefensible: philosophers who deny the existence of consciousness (with what faculty?) or geneticists who persist in arguing (in Darwin’s name but contrary to his intuitions) a mechanistic ‘selfish gene’ theory of evolution, a model as superannuated as Newtonian physics.

Even this undertaking is not the book’s central concern, for McGilchrist then examines even deeper questions: the truth about time, flow and movement, space and matter, consciousness, purpose and, as a tremendous capstone, our sense of the sacred. These are areas where we cannot confine ourselves to left-hemisphere techniques of analysis, because to analyse something is to reduce it to parts, whereas these topics are sui generis and cannot be separated or broken down. (Zeno’s paradoxes expose the delusive effect of atomising time: Achilles never catches the tortoise.)

Instead, McGilchrist invites us to see the world synthetically, recognising the necessity of the left hemisphere but the superiority of the right. The world is revealed as composed not of static objects (the ‘Things’ of the book’s title), but of dynamic processes and relationships; a world not separated from and dispassionately observed by us, but one that only through us comes into being — in which, as Yeats says, we cannot ‘know the dancer from the dance’.

McGilchrist seeks to give an account ‘at last, true to experience, to science and to philosophy’. The range and erudition are astounding (the bibliography alone runs to 180 pages). Even if one used it for no other purpose, his book is a treasure store of quotations — a polymath, he has read and seems to remember everything. He stands upon the shoulders of the giants whose words he amply cites. His forebears include Heraclitus (not Plato), Pascal (definitely not Descartes), Goethe, Wordsworth, Schelling, Hegel, Heidegger, William James, Whitehead and Bergson. Drawing out the implications of quantum physics, he discerns an ever-unfolding pattern and purpose in the cosmos and, while rejecting the propositions of organised religion, he ends up on the side of God (for want of a better verb), meanwhile giving the reductive atheist position a formidable kicking.

Yet there is nothing wacky or tendentious about this book. McGilchrist writes readably and with poetic sensibility. The tone is courteous (except in the face of others’ intolerance), modest and above all wise. Those who do not normally read about science or philosophy will never do so in better company. Like the Bible in a Victorian drawing room, this is a book that you should keep permanently open, for the Oxford prof has a point: after reading it you will never see the world in the same way again.

Comments