The new Labour government is supposedly committed to ‘defend[ing] our sovereignty and our democratic values’, as its manifesto put it, but it appears to have stumbled at the first hurdle, delaying a key measure for countering the influence of hostile states, which MI5 has described as essential for Britain’s national security.

The foreign influence registration scheme (FIRS) would for the first time force anyone in the UK acting for a foreign power or entity to declare their activities. It was due to be implemented later this year, part of a new National Security Act that represents the biggest revamp of the UK’s espionage laws in more than a century. FIRS would require those working for a foreign government to declare their activity or face prosecution. It was described by former security minister Tom Tugendhat as a tool to ‘deter foreign powers from pursuing their pernicious aims through the covert use of agents and proxies’. He also said that ‘MI5 have been clear that this scheme is essential if we are to properly fight our enemies’ attempts to interfere with our country and influence our future’.

News of the delay was quietly slipped out by way of a notice on the Home Office website, which said the scheme will no longer be introduced this year. Government sources, cited by the Times, blamed the election and the change of government for the delay, since regulations to implement the scheme needed more time. However, other officials blamed wrangling within the government, with the Treasury and the Foreign Office concerned about its impact on the economy and Britain’s diplomatic relations – for which read, they had a bout of cold feet on China.

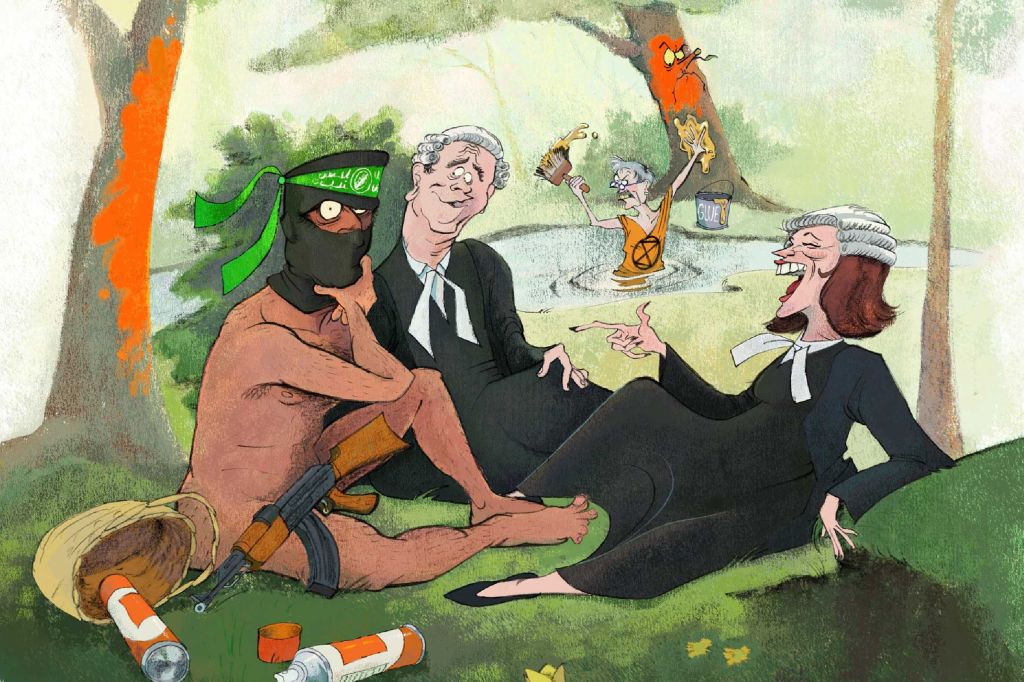

That an increasingly hostile China is an enormous threat to the UK seems obvious, as evidenced in activities ranging from rampant cyber espionage and other technology theft to brazen influence operations in parliament and academia. The Chinese Communist party’s malign and brazen interference in UK politics was demonstrated in June when the City of Edinburgh Council shelved plans for a new ‘friendship arrangement’ with the Taiwanese city of Kaohsiung, following fears it could harm relations with China, which claims Taiwan as its territory. The aim had been to strengthen cultural and commercial links between the two cities, but it fell victim to lobbying from the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Airport and Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce, which warned the move could result in sanctions on the city and reduced trade, tourism and student numbers. The council also feared cyberattacks. These organisations had faced pressure from the Chinese consulate-general, which at one point warned that Chinese students, who number around 7,000 in the city and on whom the university is highly dependent, might spontaneously decide they are no longer welcome.

There has been fierce corporate lobbying to prevent Beijing being placed on the top tier of FIRS alongside Iran and Russia and reserved for countries posing the highest risk. This tier would require greater disclosure about contacts with those countries, including contractual obligations and other dealings. It is modelled on a similar scheme introduced in Australia after Beijing was accused of interfering in Australian politics. Among the fiercest lobbyists have been HSBC and Standard Chartered, banks with enormous business interests in China. HSBC has been accused of complicity in repression for closing the accounts of Hong Kong pro-democracy activists and both banks backed the territory’s national security law, imposed by Beijing and effectively snuffing out democratic freedoms. Both have responded to criticism by arguing that they must obey the laws of the jurisdictions in which they operate, as they awkwardly manoeuvre along the growing geo-political fault lines between China and the West.

Labour inherited from the last government a suite of new security measures – including the new National Security Law, a National Security and Investment Act designed to tighten scrutiny of foreign investment, stricter rules on public sector procurement to exclude vendors who posed a security risk, and a new Research Collaboration Advice Team to help academia manage national security risks in international collaborations. Collectively they are potentially very powerful, but they remain largely untested, with details to be fleshed out, and they leave much to the discretion of ministers and officials.

Labour has promised an audit of the UK’s relationship with China in order to move on from Tory ‘inconsistency’, yet it is grappling with the familiar issue of balancing economic interests against strategic and human rights issues. Though that is in many ways a false dichotomy since the CCP does not recognise the distinction, routinely using trade, investment and market access as tools of coercion. Shortly before the election, Labour warned China that it would not tolerate interference in UK democracy. Bending to corporate and Chinese pressure and putting the foreign influence registration scheme on hold is a curious way of demonstrating that.

Comments