The problem with Keir Starmer’s approach to Brexit is that it fundamentally misunderstands the country. It isn’t that the Leave-voting public have realised that they made the wrong choice, foolishly tricked by the slogan on the side of a bus a decade ago. Voters in Grimsby have not suddenly been won round to the virtues of the Common Fisheries Policy. Most Leavers do not suddenly think shorter queues at the airport in Sofia is worth the downward pressure on wages caused by thousands of young Bulgarians who (understandably) will think Britain’s £12.21 minimum wage is more attractive than Bulgaria’s roughly £3 per hour.

The reason people feel dissatisfied with Brexit is not that the UK has diverged from the EU but because it hasn’t diverged enough. Leave voters were rejecting a political economy that concentrated wealth in London’s financial and creative industries and sucked out meaningful employment from other parts of the country. It’s globalisation that voters are fed up with.

Brexit was a constitutional ‘revolution’ in the old meaning of the word – a return to the original state of things. It returned to the government full control of industrial policy – trade, state aid, nationalisation, immigration, procurement, fishing, agriculture. Brexit brought back these powers along with an expectation of a much more active state; this was plain to the public but perhaps less so to the political class. That fundamentally different state was the real test of Brexit’s success. Boris Johnson understood this better than most. Levelling up was absolutely the right strategy, but it didn’t go nearly far enough. Regional policy has to be much more than grants for high-street facelifts.

The fact Conservative governments squandered these newfound powers isn’t surprising. Brexit introduced policy levers much more commonly associated with left-wing governments. It was a Labour government which, by history and instinct, ought to have had the most to gain from Brexit, if it were willing to deploy those tools. What would that mean? For one thing, state aid – grants, tax concessions and low-interest loans – to revive old industries and develop new ones in economically depressed parts of the country. For example, fishing is a capital-intensive industry. You need to catch a lot of fish before you can pay back the costs of your vessel, but if the British government were serious about a revival of this industry, it would aid those capital investments by providing long-term, low-interest loans to fishing startups. With control over our own stock, it could be managed in a way that was environmentally responsible. A Labour government could attach conditions about unionisation and workers’ conditions to such loans, too.

The fundamental problem is that Labour is not prepared to challenge a stale economic orthodoxy. Open flows of capital, labour, goods and services did not stem economic decline; in many cases, they worsened it. A new agreement to subsidise the education of German undergraduates in London may delight Starmer’s friends in Camden, but it does nothing but irritate voters in Grimsby. Starmer and Rachel Reeves’s attachment to Treasury orthodoxy is the reason voters are turning to Reform.

When the markets reacted to Truss’s mini-Budget, shadow chancellor Reeves vowed that ‘Never will a prime minister or chancellor be allowed to repeat the mistakes of the “mini” Budget.’ As Chancellor, Reeves has wrapped herself in a fiscal straitjacket, delighting the City while leaving low-income pensioners to go cold in the winter.

No government has taken up the real challenge of Brexit – to use this constitutional revolution to bring about an economic one. In our risk-averse public sector culture, that may be seen as too much of a step into the unknown. But for the sake of the country’s economic revival and for the party’s own survival beyond the next election, the Labour government needs to learn to love Brexit.

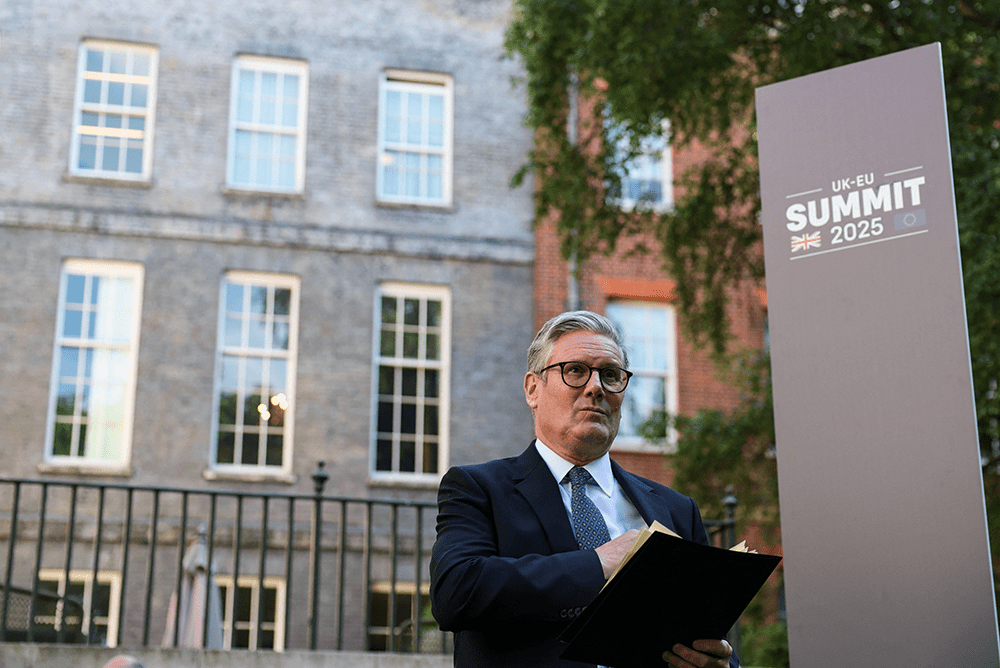

Does Labour need to learn to love Brexit? Richard joined the Edition podcast alongside prominent Tory Brexiteer and peer Dan Hannan to discuss:

Comments