James Forsyth reviews the week in politics

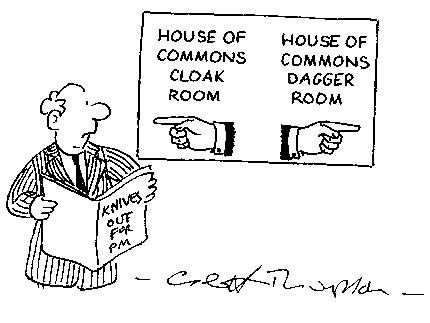

There is something wonderfully self-perpetuating about mutiny in politics. Any attempt to depose a leader, successful or otherwise, triggers a cycle of rebellion. The danger for Labour after last week is being sucked into this cycle where treason begets treason. Indeed, the conspirators against Brown cite his actions as justification for their own. As Barry Sheerman put it, when challenged about whether he was betraying his leader, ‘I don’t need anyone who undermined the previous Prime Minister and who was utterly disloyal telling me that I am disloyal.’

When a leader has broken the bonds of party loyalty, he struggles to demand loyalty himself. Iain Duncan Smith, a Maastricht rebel, could never rely on the fealty of his party. Equally, Brown does not have the moral authority to call for loyalty because he was known for anything but when he was Chancellor. The two men most tipped to be his successor, Ed Balls and David Miliband, will also have trouble on this front.

If Ed Balls became leader, everyone in the party would still remember how he stirred up dissent against both Tony Blair and his policies. There would be many who would take pleasure in causing his leadership problems. ‘Those to whom evil is done/ Do evil in return’, as W.H. Auden wrote. In politics, turning the other cheek is in no one’s bible.

Balls, though, is unlikely to win the leadership. His main advantage is that in the words of one former Cabinet colleague of his, ‘he is the only person mad enough to really want it.’ One is already hearing of the squeeze being put on party figures to get them to promise their support to him. But Balls is far too factional and divisive a figure to win. He might come out of the gate with an impressive amount of support but that would be it. Rather like Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primaries, if you are not for Balls, you are against him and many Labour MPs are proud to belong in the latter category.

Already, some are talking about standing for leader just to draw support away from Balls and let someone else through. It should not be forgotten that the trigger for James Purnell’s resignation in June was being offered the education job, a sign that Ed Balls was going to become Chancellor. Lord Mandelson only managed to quell this revolt against the Prime Minister by assuring his Cabinet colleagues that Balls would stay put after all.

David Miliband is a more credible contender than Balls. Although regularly labelled a Blairite, his position is far more complex. Miliband was shuffled out of Blair’s Downing Street and into a safe Labour seat before the 2001 election because the then Prime Minister felt his commitment to market reform was lacking. One former No. 10 colleague of his confirms that Miliband could be persuaded of Blairite arguments for market reform, but that was not his instinctive view.

A hint of what a Miliband leadership might offer in policy terms came on Monday, when Mr Purnell — a close friend — published an essay in the Guardian setting out a new intellectual agenda for Labour. Purnell, who has behaved with immense dignity since his resignation, offered a considered critique of the third way and a set of policies that broke away from the Brownite–Blairite shackles. It was an agenda with which nearly all parts of the Labour party could do business. One senior figure on the left of the party told me, with considerable surprise, that he could sign up to all of it.

Nevertheless, there would be those who would not accept the legitimacy of a Miliband leadership. His ‘come and get me’ approach to the Labour leadership in the summer of 2008 is still remembered and ridiculed. There were echoes of this last week, when after hours of delay he produced only the most lukewarm statement of support for the Prime Minister.

If Labour wants to break this cycle, it needs to pick someone who can credibly demand loyalty because they are perceived to have offered it to every leader that they have served. Only two leadership contenders fit this criterion: Ed Miliband and Jon Cruddas.

The obvious obstacle to Ed Miliband standing is his surname. Some in the Labour party hope that the party’s greybeards — Lord Mandelson and Jack Straw — will persuade David to stand aside for his brother for the sake of party unity. But this seems unlikely. When David was considering whether or not to accept nomination for the role of EU Foreign Minister, part of the discussions, supporters say, were about whether he should leave the British political field free for Ed. Having decided to stay, Miliband senior has almost certainly decided to stand.

This leaves the backbencher Jon Cruddas. It is easy to dismiss him given his lack of ministerial experience, or his left-wing economic views (he has flirted with the idea of a maximum wage). But his opponents underestimate Cruddas at their peril. He came from nowhere to win the most ‘first preference’ votes in the deputy leadership contest in 2007 and is a formidable campaigner. For all his leftism, he conveys an honesty and authenticity which wins him admirers from across the spectrum.

Friends are adamant that Cruddas will run for leader if Labour loses the next election. If he can present himself as the clean-hands candidate who can move Labour beyond the divisions of the Blair–Brown era, he will stand a good chance.

Labour should learn a lesson from its current troubles: contests are a good thing. Labour would be a far more united party if Mr Brown had stood against Blair in 1994 rather than having been persuaded to stand aside by a vague promise of the crown at a later date. Had someone challenged Mr Brown in 2007, the party would have had a chance to see and vote on his failings.

The party needs to accept that out-in-the-open competition is a good thing and encourage all those who want to stand in the post-election contest. As the Tories found in 2005, it can be strikingly cathartic. But if whoever triumphs in that vote is to have a chance of becoming Prime Minister, he must make his colleagues pay heed to another line from that Auden poem. ‘We must love one another or die’.

Comments