The term ‘dyslexia’ has always been emotive, and it remains so. Julian Elliott and Elena Grigorenko’s book The Dyslexia Debate (2014) has done nothing to dispel the controversy. In a recent paper, ‘Why Children Fail To Read’, Sir Jim Rose, an apologist for dyslexia, said, ‘Dyslexia continues to come under fire as a myth. At its unkindest, this myth portrays dyslexia as an expensive invention to ease the pain of largely, but not only, middle-class parents who cannot bear to have their child thought of as incapable of learning to read for reasons of low intelligence, idleness, or both.’ Rose emphasises that both environmental and genetic factors influence reading ability and finishes by saying, ‘Dyslexia is not yet well enough understood as an extreme reading disorder for which we have precise solutions,’ which isn’t a particularly reassuring conclusion. Whatever the cause, early identification of pupils who are struggling to learn to read and write remains an obvious ambition.

Dyslexia falls under the umbrella term of Specific Learning Difficulties (SpLD). A helpful and up-to-date overview of SpLD, including dyslexia, is provided by the British Dyslexia Association. Put briefly, children with a dyslexic profile experience difficulties with reading, spelling and writing. Characteristics include impaired phonological (the sounds that make up language) awareness, slow information processing, issues with working and long-term memory, and sometimes other learning difficulties.

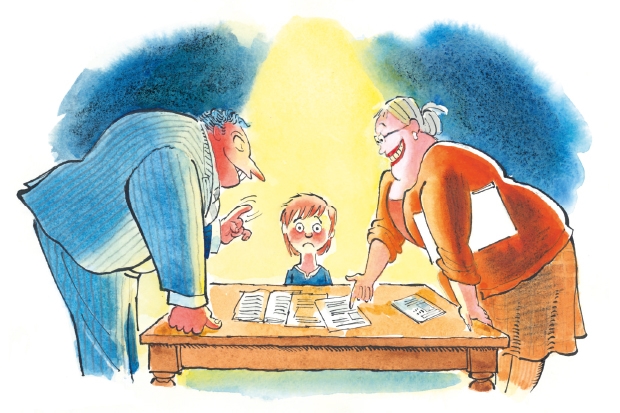

So how does an understandably anxious parent help? If you suspect your child has dyslexia, the first port of call is your child’s class teacher. A collaborative relationship with school is fundamental: ask whether they agree that there is a problem. If they do, ask what support your child is receiving in school and how best you can help with homework. The last thing a child who struggles with words and numbers wants is to come home exhausted and frustrated to find that mummy has morphed into a teacher, Mrs McGhastly, who launches into an overenthusiastic rigmarole of practising sounds, times tables and so on. Failure to engage stresses everyone, including the hamster.

Crucially, to help your child you will need patience. In spades. Learning is anything but a linear progression and for primary-school children with reading difficulties, concepts and skills may need to be continuously revisited for them to become embedded and automatic. Develop a routine. High stress levels are not the sole domain of the parent — a child will often suppress his or her frustration and sense of failure during the school day, which may lead to emotional outbursts at home. Homework will be achieved more successfully after a period of ‘decompression’, which may include some quiet time and a spot of fuel.

Dyslexic children often perform best when they can absorb information through more than one sense, along the lines of the Chinese proverb, ‘I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.’ It is encouraging for the child to understand that how they learn is just as important as what they learn. Boredom is often the biggest hurdle when it comes to reading. There is always a danger that a book that is within the reading capability of a dyslexic child is dull or age-inappropriate. Thus some careful investigation and consideration is worth the effort. The publishers Barrington Stoke now have an excellent range of high-interest books in an easy-to-read format for different levels of reading ability. Audio books can usefully increase a child’s receptive and expressive language skills.

Getting your child to write may be one of the hardest things you have to do. Do not expect too much too soon. Choose a topic that interests your child. Help to generate ideas. Teach your child to check their own work, paying attention to any specific weak areas. If handwriting is poor, and your child cannot touch-type, scribe for them or explore speech-to-text software.

The purpose of homework is to consolidate. Minimise potential misunderstandings over homework by asking that tasks be emailed home or printed out and stuck into your child’s homework diary. Think about where homework should take place. Starting at a clear, distraction-free table may also prove helpful for those who are prone to scatter their books. Divide homework tasks into manageable chunks. Read instructions aloud and practise a couple of examples. Make sure there are breaks between tasks. Use a countdown timer. Be well-organised — dyslexic children tend to find organising their lives challenging. And simplify life by ensuring that everything needed for the next school day is packed up the night before and placed by the front door.

Exams are every parent’s –— and every child’s — bête noire. Dyslexic children simply cannot cram for exams and need to start revising much earlier than other children. To chunk learning into small bite-sized bits is just one ploy. It can be useful to ask a child to reflect on what works for them and what doesn’t, and why.

So what other help is out there for parents? Local Dyslexia Associations run by volunteers can be immensely helpful in providing support and encouragement. Another excellent resource is the Parent Champions website, with useful tips for reading, spelling and memory training.

There is also help available in the form of independent specialist teachers, who can be found either through the national index of tutors held by Patoss, or through the British Dyslexia Association.

Since the introduction of the Children and Families Act 2014 and the new Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice (SEND), class and subject teachers at school, supported by their school’s SEN co-ordinator, are responsible for regular progress assessments, and support should follow. Parents should be fully involved in and informed about any special educational provision deemed necessary, including the need for specialised evaluation by, for example, an educational psychologist, or speech and language therapist.

Tremendous help is also available from ‘assistive technology’. Learning to touch-type is one of the most useful skills a child with dyslexia can acquire. Touch-type Read and Spell is a tried and tested method and touch-typing centres, which often run intensive courses during school holidays, may provide convenient alternatives. There is also a wide range of apps for dyslexia — just search online you will find a wide choice, or the BDA have also put together their own list.

Finally, the Council for the Registration of Schools Teaching Dyslexic pupils (CReSTeD) maintains a register of the many schools and establishments that cater for children with learning difficulties. Initially confined to independent schools, CReSTeD has extended its work into the maintained school sector. CReSTeD also provide details of teaching centres where children can find additional support outside their day-to-day schooling.

Comments