Let councils take the decisions – and the blame

If there’s something strange in your neighbourhood, the coalition wants you to call ‘bureaucracy busters’. This may sound like an irritating bit of alliterative spin, but

it’s actually one of the government’s most radical proposals. The idea is to help individuals and community groups overcome the regulations and government restrictions that stand in the

way of innovation at a local level: in other words, to clear a way for the big society.

Bureaucracy busters is the brainchild of Greg Clark, the minister for decentralisation. Clark has a degree from Cambridge and a doctorate from the LSE, and is astute enough to have grasped that

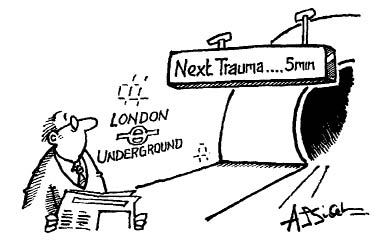

politicians can’t do things alone. As he struggled with the bureaucratic maze of his own department, he realised how difficult it must be for the public to make their way through the

regulatory obstacle course. If innovation was to come from the ground up — as the coalition wants it to — the people would need help.

Clark’s plan is that any community-minded citizen who is running up against the dead hand of local bureaucracy will be able to call and request the help of his bureaucracy busters. This

epitomises the coalition’s approach to localism. Rather than just viewing it as handing power down from Whitehall to local authorities, they are trying to pass power all the way down to

individuals.

The Localism Bill, which will be introduced into parliament towards the end of this month, is described by Clark as an exercise in antitrust law. Its aim is to stop local government from abusing

its dominant position. Crucially, the bill is intended to give people rights against government at every level.

The high-minded reason for doing this is that both the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats want to strengthen the power of people and weaken the power of government. (This enthusiasm is not

universally shared by the parties’ councillors, as the battle to free schools from local authority control has demonstrated.) The low-minded reason is that local authorities could become

obstacles to reform and centres of opposition to the government — as they were during the Thatcher era.

Local authorities were one of the principal victims of the spending review. Councils will now see their budgets cut by more than 7 per cent every year for the next four years, while the budget for

the Department of Communities and Local Government will be cut by more than 50 per cent. There is, obviously, a danger that this could rebound on the coalition: that aggrieved councils could just

raise taxes or cut popular services to make up the gap and blame it all on central government cuts. Given how Westminster-centric our political and media culture is, this approach would have a good

chance of success.

Whitehall is aware of this danger and keen to head it off. The Localism Bill will allow for a local referendum on any council tax increase that is substantially above the rate of inflation, making

local politicians take responsibility for any tax hike.

Eric Pickles, the avuncular Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, is an unlikely Machiavelli. He has spent the past few years playing up his reputation as a plain-speaking

Yorkshireman to such an extent that he was in danger of becoming a parody of himself. But now he is deftly making it nigh-on impossible for councils to cut frontline services and blame it all on

the coalition’s austerity agenda.

Pickles has delivered a series of pre-emptive strikes against local authority opposition to this agenda. His first, the requirement that councils should publish details of all expenditure over

£500, was a dramatic extension of the Conservative plan in opposition to release the details of all government expenditure over £25,000. The aim is to force councils to cut

non-essential spending rather than popular services. Pickles’s demand that councils comply with this measure by January means that the information about how councils spend taxpayers’

money would be public before the cuts start biting in April.

Pickles has also cannily implemented restrictions on council-funded local free-sheets. These free-sheets, which often amount to little more than local authority propaganda, have had a devastating

effect on independent local newspaper advertising and sales. Under Pickles’s plans, councils will only be allowed to publish their ‘town-hall Pravdas’ four times a year. This

should help keep a robust and independent local press going. And a vigorous free press can in turn capitalise on this new level of transparency to inform the public about the real levels of local

government inefficiency and waste. If a local electorate knows more of the ugly details of how a council spends its money, it is less likely to accept that frontline services have to be cut because

the council is receiving less money from central government.

Pickles’s ability to think several moves ahead should ensure that the ire of voters is directed at local government waste, not central government cuts. If he can make voters see things from

this perspective, it will be quite an achievement.

Still, as Tory localists such as Douglas Carswell and Dan Hannan have long argued, a true revival of local democracy will not come until the money for local government is raised locally. At the

moment, only a quarter of the money spent by local authorities comes from taxes levied locally.

Nick Clegg is leading a review of local government finance that is meant to address this problem. But the coalition, whose Tory members are still scarred by the memory of the poll tax, is already

ruling out any new local council tax.

The idea of turning VAT into a locally determined sales tax has been mentioned in Clegg’s review. Such a move would be impossible, however, because the EU requires VAT to be levied

nationally. Nevertheless, any serious attempt to narrow the gap between what local government spends and what it raises will require turning some national taxes into local ones.

Two simple tests will decide whether Clegg and Clark’s localism agenda has worked. Is local government relying on money it has raised itself? And can people enact change in their communities

without needing a bureaucracy buster to help them? If the answer to those questions is yes, then the coalition will have succeeded.

Comments